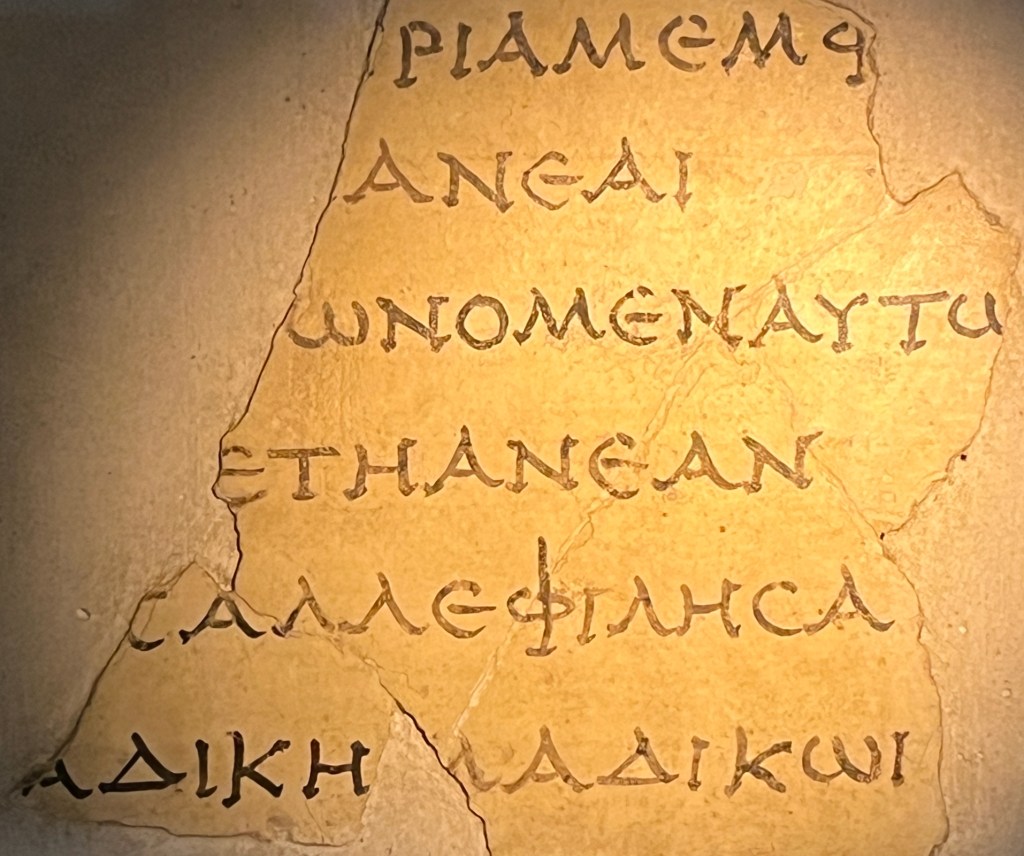

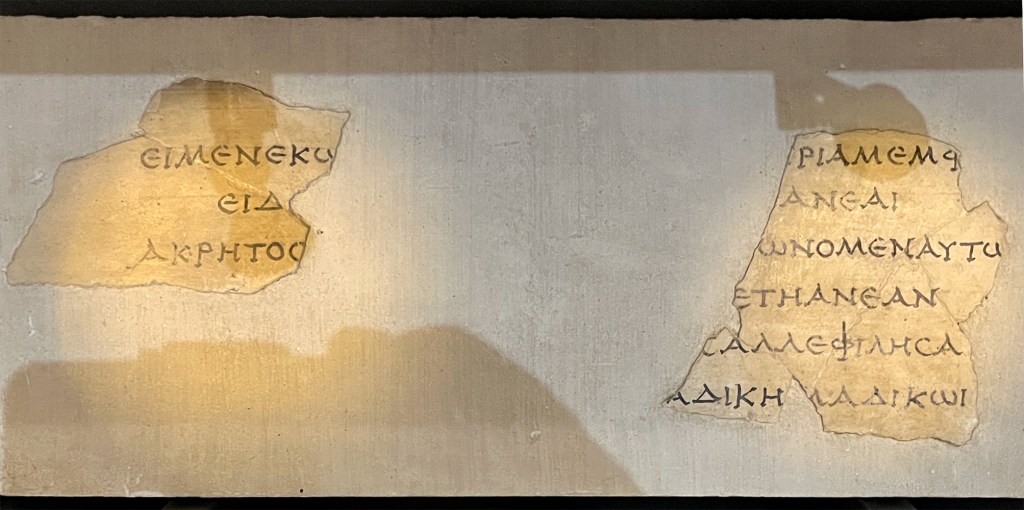

At the Capitoline Museum in Rome, there are a series of rooms dedicated to finds from the various garden areas uncovered in the area of the Esquiline hill in the late nineteenth century. Tucked away in a corner of one of these rooms are some bits of painted fresco with Greek writing in a very nicely executed script. The fragments were found in situ on the exterior of the so-called Auditorium of Maecenas in 1874 (the actual function of this building is open to debate). The mounting and lighting of the fragments in the museum are a little less than ideal, so please excuse the shadows, reflections, and the general quality of the image:

The pieces are mounted in a way that indicates how much text is missing in between the two large chunks. We know the amount of missing text within tolerable limits because the lines are known to be an epigram attributed to Callimachus. A drawing was published in 1875 and an edition appeared in 1878.

And in fact there is a new edition of the epigrams of Callimachus, fresh off the presses (October 2025) by Susan Α. Stephens and Benjamin Acosta-Hughes. Here is their full text of the epigram:

Εἰ μὲν ἑκὼν, Ἀρχῖν᾽, ἐπεκώμασα, μυρία μέμφου,

εἰ δʼἄκων ἥκω, τὴν προπέτειαν ἔα.

ἄκρητος καὶ ἔρως μʼ ἠνάγκασαν, ὧν ὁ μὲν αὐτῶν

εἷλκεν, ὁ δʼ οὐκ εἴα τὴν προπέτειαν ἐᾶν.

ἐλθὼν δʼ οὐκ ἐβόησα, τίς ἢ τίνος, ἀλλʼ ἐφίλησα

τὴν φλιήν· εἰ τοῦτʼ ἔστʼ ἀδίκημʼ, ἀδικέω.

And here is their translation:

If of my free will, Archinus, I had brought a revel, blame me a thousand times,

but if I have come against my will, permit my rashness.

Unmixed wine and love compelled me, of which the one

dragged me, the other would not allow me to let my insolence go.

When I came, I did not shout out who I was and whose son, but I kissed

the doorpost. If this is wrong-doing, I do wrong.1

Stephens and Acosta-Hughes provide an excellent and thorough line-by-line commentary, as they do for all the epigrams (just one quibble: In connection to these plaster fragments, they write that “the inscription no longer exists,” but here it is! The didactic material at the museum gives no indication that these pieces are facsimiles).

The script is quite interesting. It was applied with a brush but shows an attempt to mimic the effects of the use of a stylus for serifs, occasionally giving some vertical lines ends that look like arrows (e.g. tau as ↧).

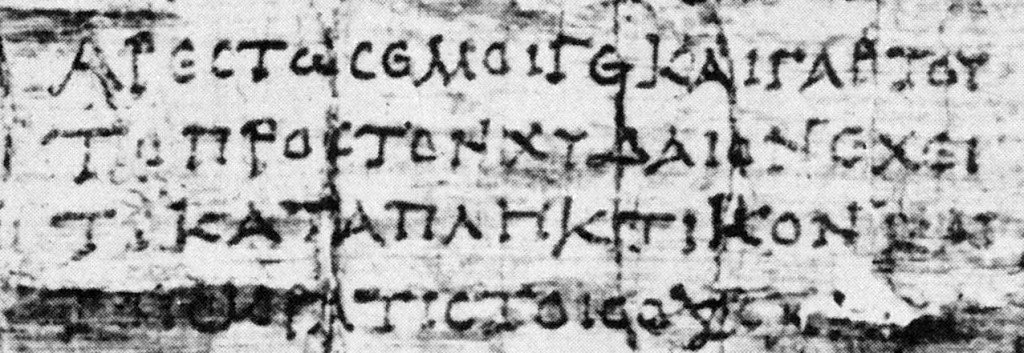

The script is similar to that found in some surviving papyri. It features letters of a basically square modulus, with only the phi really breaking bilinearity. The alpha is often written in three clear strokes, the epsilon often shows a little bit of space between the curve and the central stroke, and the phi has a somewhat compressed loop and prominent foot. The hand reminds me of some Herculaneum papyri, such as P.Herc. 1507:

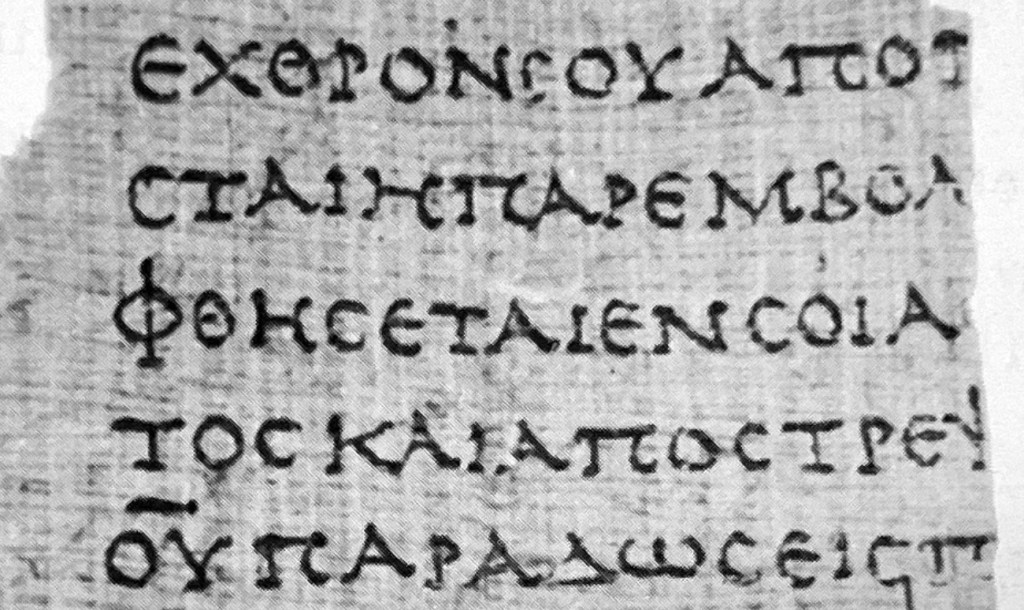

It also brings to mind certain Jewish manuscripts, such as P.Fouad inv. 266:

Both of these manuscripts have been assigned to the first century BCE, and it seems plausible that our lines of Callimachus could have been written in the same period (i.e., during the first or second phase of the building’s use), although a later date cannot be ruled out.

And where, exactly, were these lines displayed? The excavators give us a description:

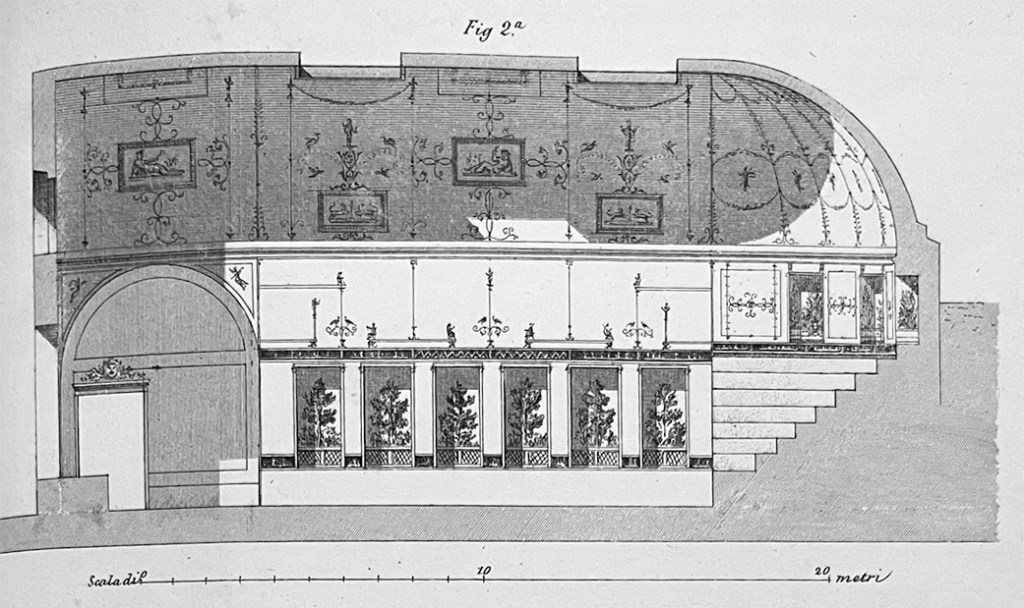

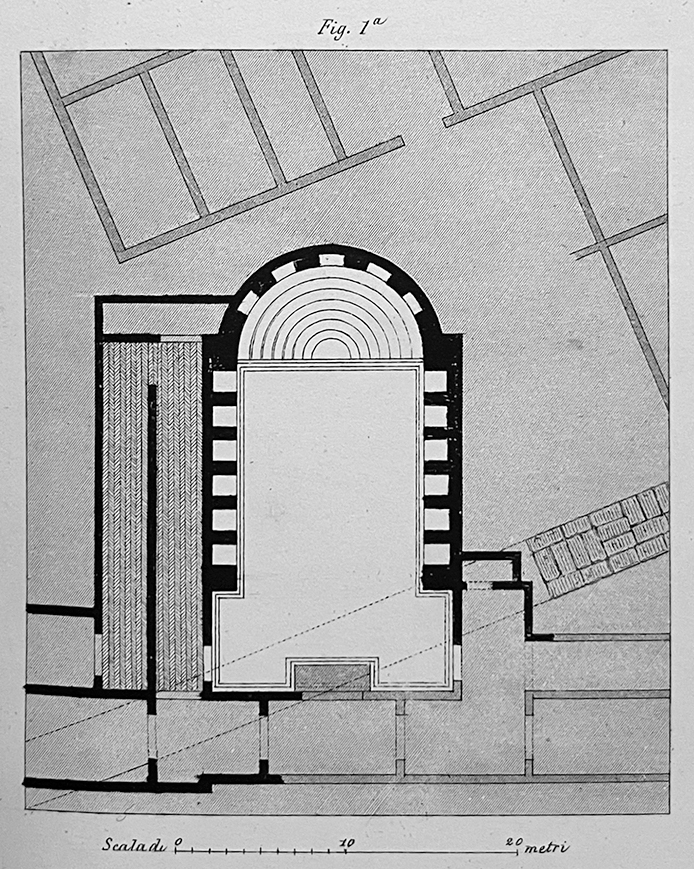

“Some passages of a Greek epigram, which, with a brush dipped in black, had been written on the white plaster of the external wall of the semicircle, near the middle of its curve. The point where these verses could be read is about two-thirds of the height of the wall; so high that, in the present state of the excavation, one would have to get up on a ladder; but when the building was in its original condition, that is to say, sunken the ground up to more than half its height, it was possible to write comfortably in that spot, standing in front of the wall. The part of the plaster on which the epigram had been written, although torn into pieces and lacunose, was detached, by the care of this Commission, and is preserved among its collections of antiquities.”2

The top plan and reconstructed profile drawing offered by the excavators give a reasonably good idea of the position of the verses “on the external wall of the semicircle.” Notice the hypothesized ground level shown at the right side of the profile drawing.

It’s nice to learn of the existence of these fragments, and it’s wonderful to be able to recover their context, at least to a certain extent.

- Susan A. Stephens, Benjamin Acosta-Hughes, Callimachus: The Epigrams (De Gruyter, 2025), 271. ↩︎

- V. Vespignani and C.L. Visconti, “Antica sala da recitazioni, ovvero auditorio, scoperto fra le ruine degli orti mecenaziani sull’ Esquilino,” Bullettino della Commissione Archeologica Comunale di Roma (1874) at 162: “Alcuni brani di un greco epigramma, il quale col pennello intriso di nero era stato scritto sull’ intonaco bianco del muro esterno dell’ emiciclo, quasi nel mezzo della sua curvatura. Il punto in che leggevansi questi versi corrisponde a circa due terzi dell’ altezza del muro; talchè, nello stato attuale del disterro, sarebbe necessario ascendervi con una scala: ma quando l’ edifizio era nelle sue condizioni primitive, cioè a dire, internato nel suolo per più della metà di sua altezza, poteasi comodamente scrivere in quel sito, stando in piedi avanti la parete. La parte dell’ intonaco in cui l’ epigramma era stato vergato, sebbene ridotta in brani e mancante, venne distaccata, per cura di questa Commisione, e si conserva fra le suo raccolte di antichità.” ↩︎

I believe the last word should be ἀδικῶ, not ἀδικέω. But is that an iota adscript at the end of the inscription (which wouldn’t seem right), or just a marker of the end of the epigram?

Earlier I suggested that the last word should be ἀδικῶ, rather than ἀδικέω, but I see that in texts of Callimachus’ epigrams the uncontracted diphthong -έω prevails (but not in the inscription), though, of course, it must be treated as a diphthong or monophthong for metrical purposes. I still wonder about the iota at the end of the inscription— a hypercorrection?

There is an odd footnote in Dressel’s article in reference to a variant reading in the manuscripts at the end of line 2: “Il codice scrive ὁραι, cioè ὅρα col iota aggiunto per indicareche la vocale α è lunga: di questa particolarità, che non di rado incontrasi nelle antiche iscrizioni e nei codici, anche il nostro frammento dipinto ce ne fornisce due esempi: in fine del v. 2 e 6 ⲉⲁⲓ, ⲁⲇⲓⲕⲱⲓ = ἔα, ἀδικῶ.” I was not aware of this phenomenon, and in any event, it can’t be quite right here because the omega is already long by nature, and so would require no marker.

Brent: “(just one quibble: In connection to these plaster fragments, they write that “the inscription no longer exists,” but here it is! The didactic material at the museum gives no indication that these pieces are facsimiles).”

While it would be great, I suspect museum presentation do not always volunteer that a displayed item is in fact a facsimile. Am I too suspicious of museum curators and their staff?

The Capitoline Museum generally seems pretty open about such things.

Witty word-play in this epigram: ἑκὼν/ἄκων/ἥκω, ἐφίλησα/φλιὴν, τὴν προπέτειαν ἔα/εἴα τὴν προπέτειαν ἐᾶν, and alliteration ἐπεκώμασα μυρία μέμφου.