When I think of the Biblical Majuscule, what usually comes to mind is the script of the famous Greek Bible, Codex Sinaiticus, which is usually assigned to the fourth century (though the early fifth is not out of the question). But as Guglielmo Cavallo demonstrated in his classic 1967 study, Ricerche sulla maiouscola biblica, examples of this script persist until the very end of the eighth century and perhaps beyond. I recently had occasion to look into a very late example of the Biblical Majuscule, and I find myself a little confused.

It involves one of the “new finds” from St. Catherine’s Monastery in the Sinai, Sin. ΝΕ gr. ΜΓ 012, a fragmentary parchment bifolium that is usually said to be securely dated to 861/862 CE. The bifolium belongs to Sin. gr. 210, a gospel lectionary (ℓ844 in the INTF numeration). The bulk of Sin. gr. 210 was reported as missing in 1983, but it was photographed in Kenneth W. Clark’s microfilming project in 1949. The date given for the manuscript in the microfilm is eighth century, which seems sensible given the script of the codex (a sloping pointed majuscule). The challenge is that the date given in the colophon preserved in Sin. ΝΕ gr. ΜΓ 012 is said to be 861/862 CE, which would place the codex (and its scripts) squarely in the ninth century rather than the eighth. This manuscript would then be (to the best of my knowledge) the latest precisely dated example of the Biblical Majuscule (at present, I think the generally accepted latest securely dated example is Vat. gr. 1666, a codex containing the Dialogues of Gregory the Great with a colophon dating to 800 CE).

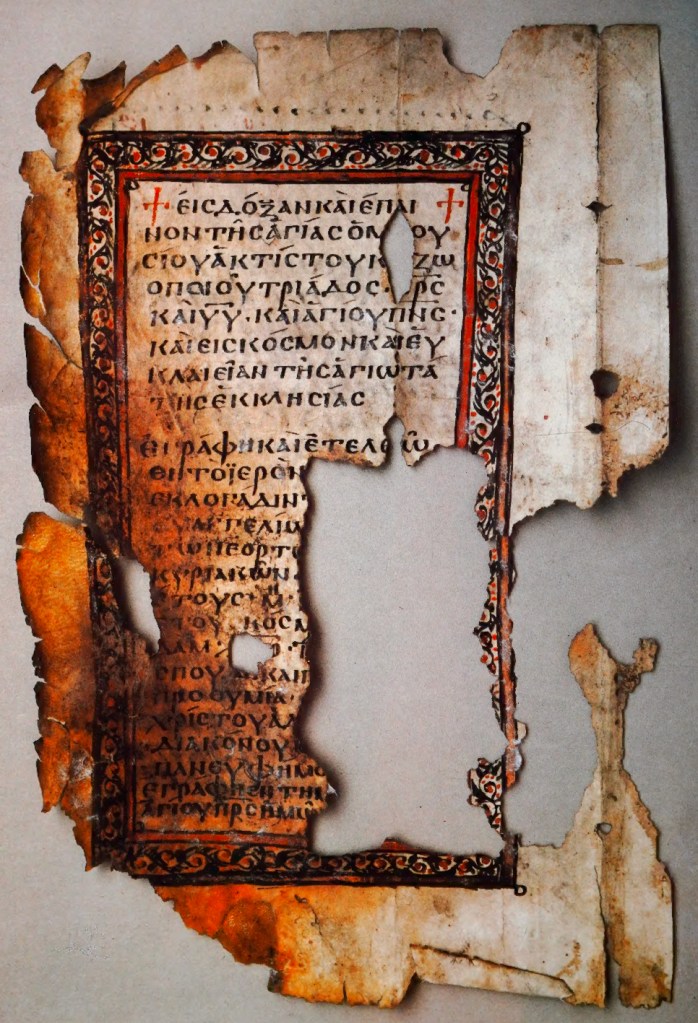

Here is an image of the page in question from Sin. ΝΕ gr. ΜΓ 012:

But note that the date is partly (actually mostly) obscured by a hole. Here is an image:

The editors read the dating formula as:

έτους κόσμ[ου ἀπὸ ἀ]δὰμ /[ϛτ]ο / ·

The date is thus restored to /ϛτο, world year 6370. Based on the assumption that the world was created in September of 5509 BCE, the equation would be 6370–5509 = 861 CE (or maybe 862, since we can’t read the month in the colophon). I can see and accept the omicron (70) for the decade digit, and the millennium digit logically must be a digamma (6000), but the crucial number, the century digit, is completely missing due to the hole in the manuscript. I’m not sure if there is anything else about this codex that would determine that the letter/number to be supplied in the lacuna must be tau rather than sigma, which would give us a date of 761 (or 762) CE.

One issue that may be problematic for restoring a sigma is that 761/762 would be, as far as I know, the earliest example of a precisely dated Greek colophon. At present, I believe the earliest example is again, Vat. gr. 1666, which is dated to April 6308 = 800 CE). So the Sinai codex would either be the earliest precisely dated Greek colophon or the latest example of the Biblical Majuscule, depending on whether we restore a sigma or a tau. Either way, an important milestone.

So, the manuscript is securely dated, in a sense (either 761/762 or 861/862 CE). The INTF Liste describes the date as “861/62?” I wonder if this is the reason for the question mark.

A fascinating post, Brent! There appears to be a trace of ink at the top of the lacuna which is straight and horizontal. If that is correct, it would support the tau more than the sigma. Perhaps this led to the reconstructed reading? Or could there have been more material preserved when the earlier/initial studies were done?

Thanks, Andrew. I think, yes, both of those are possible reasons for the tau. The editors thought a wider letter would be better given the space, but I don’t know that this is necessarily true. I wonder if there has been some distortion of the parchment at the hole, as the omicron in the numeral looks to be a rather different shape than the other instances of omicron in the text.