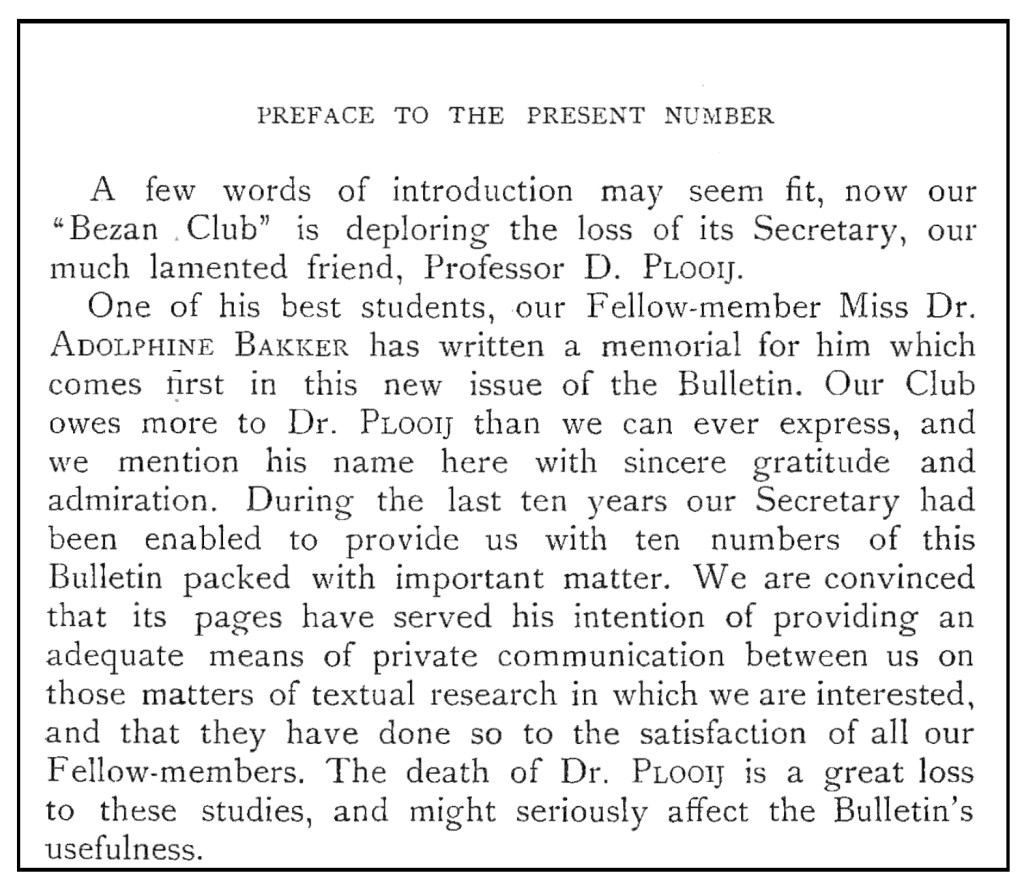

The latest issue of Novum Testamentum contains an important (open access!) article on Codex Alexandrinus:

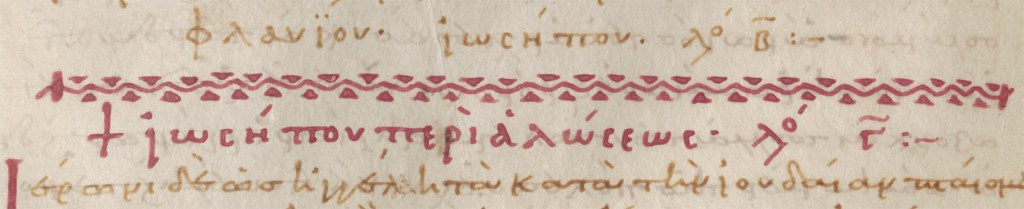

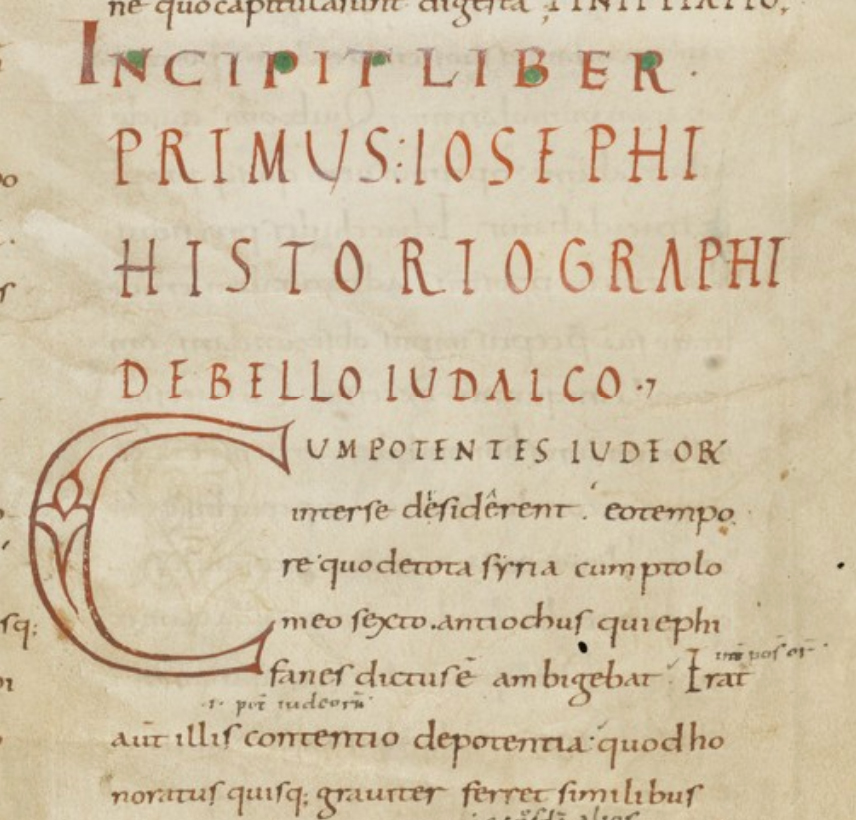

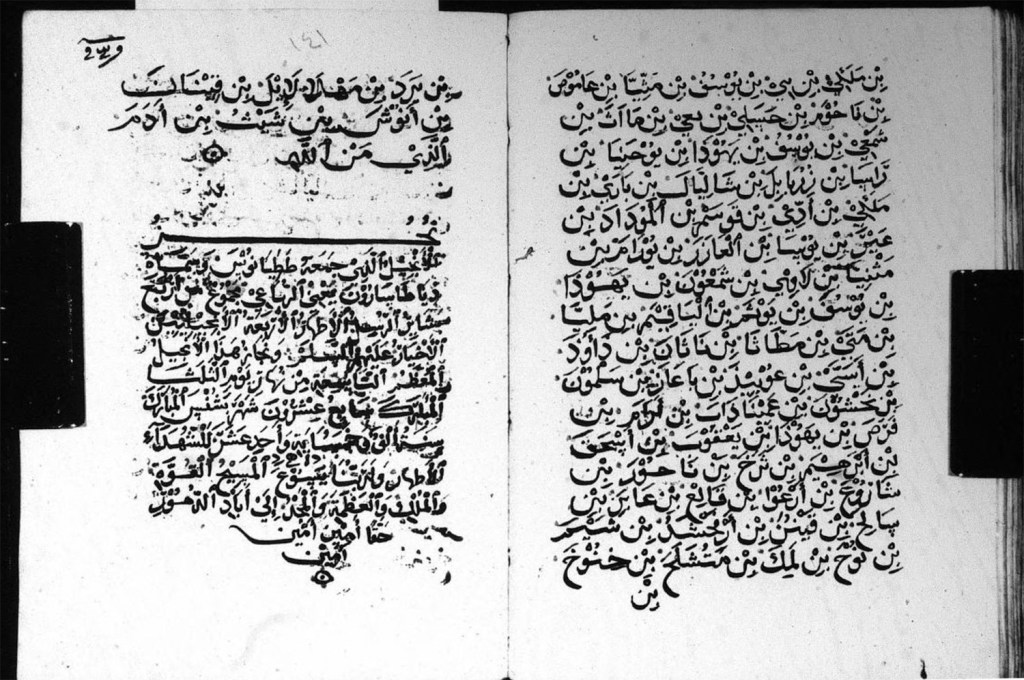

Mina Monier, “The History of Codex Alexandrinus: New Evidence from Arabic Paratexts,” Novum Testamentum 67 (2025) 501-526.

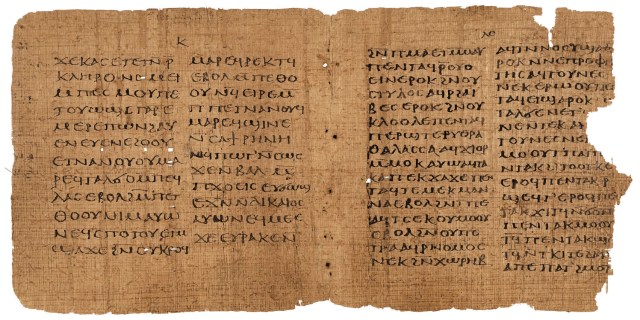

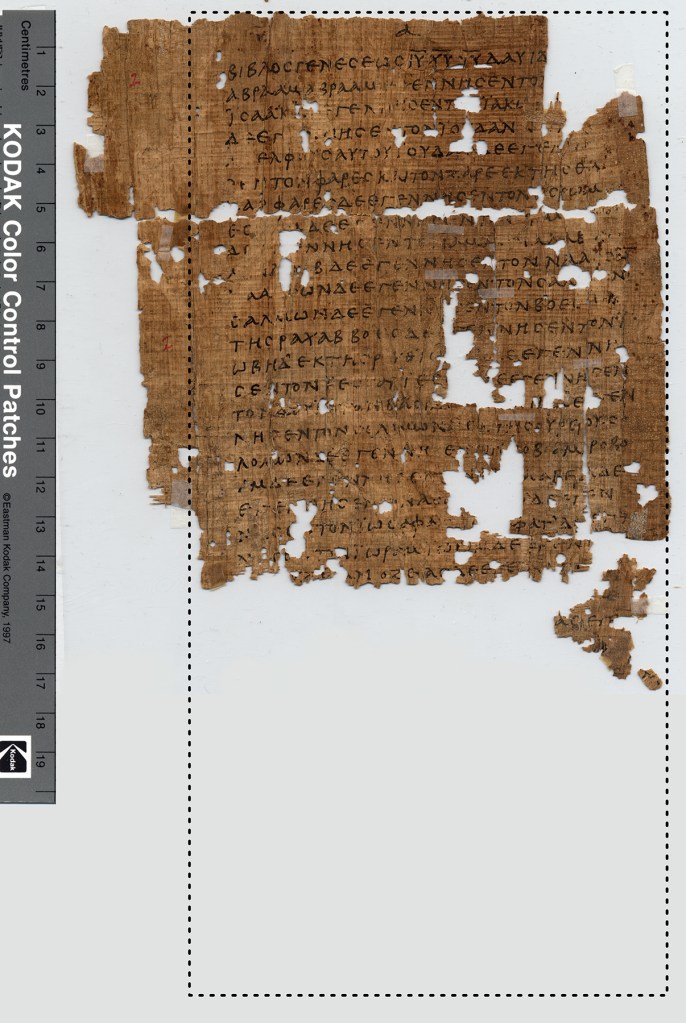

Recent scholarship on the codex has generally rejected the possibility that the manuscript was produced in Egypt (Constantinople is the most frequently named alternative; Ephesus has also been suggested). Now Monier’s article brings together several arguments that undercut the case for Constantinople and offer support for an Egyptian provenance for the codex. Among other things, the article:

- provides both an improved transcription and a richer contextualization of the Arabic endowment statement in the codex. The result is that there is no longer any reason to believe that Codex Alexandrinus came to Egypt with a group of books from Constantinople in the early fourteenth century, which has been the usual assumption since T.C. Skeat’s 1955 article on the provenance of Alexandrinus.

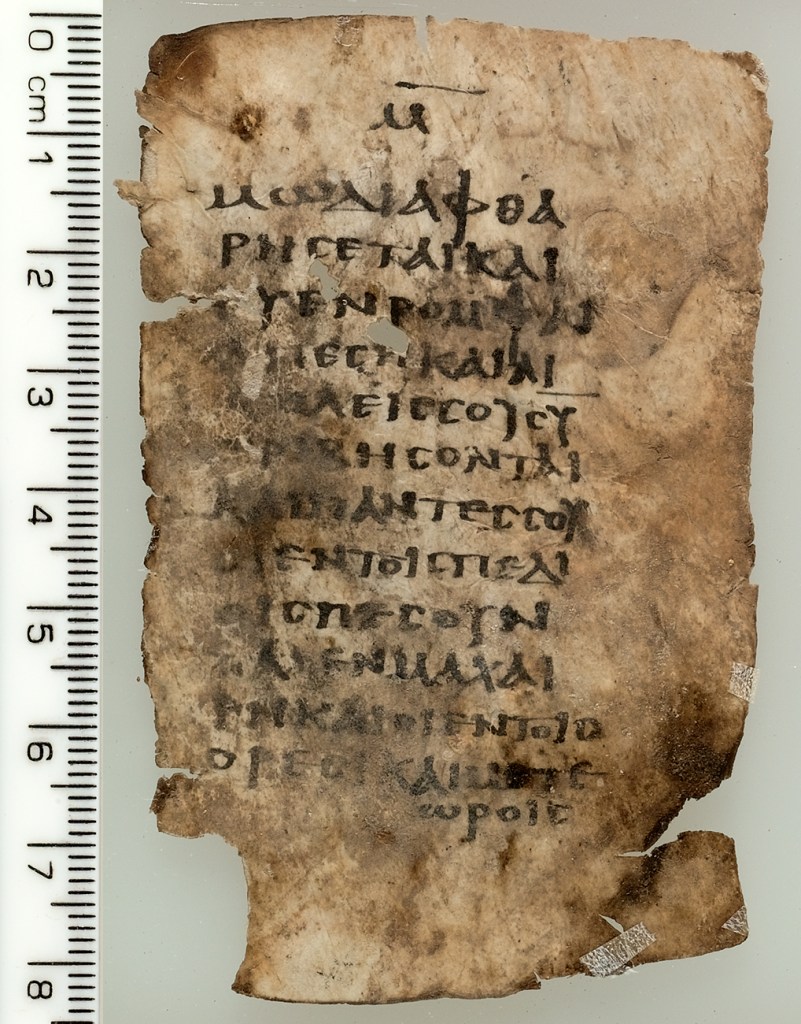

- points out that marginal liturgical notes in Arabic can be explained only in light of the Coptic paschal lectionary.

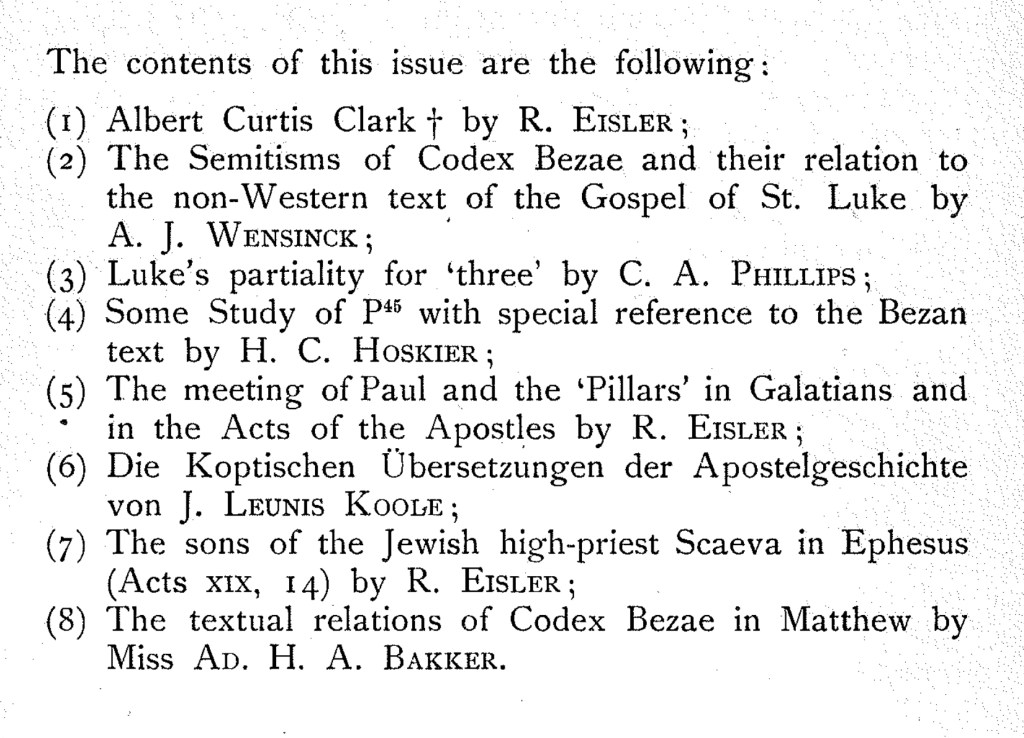

- highlights neglected Egyptian evidence for lists of New Testament books that match the curious contents and order of the New Testament books in Codex Alexandrinus (which includes 1-2 Clement and places Hebrews between 2 Thessalonians and 1 Timothy).

There is much more in the article itself (including a thorough discussion of the enigmatic reference to “the handwriting of Thecla the Martyr,” as well as a new approach to the context of the foliation of the codex). This is a fascinating read, and I have no doubt that this will be a landmark study that reorients the discussion of the early history of Codex Alexandrinus.