News services in Egypt have announced that the Mudil Psalter is back on display after undergoing conservation treatment. This was a very well preserved Coptic codex that was excavated in 1984.

It was found buried together with the body of a young girl, but, frustratingly, we don’t know the exact relationship between the book and the body. Here is what I wrote about the codex in God’s Library (2018) in the context of discussing stories about bodies buried with books in late antique Egypt:

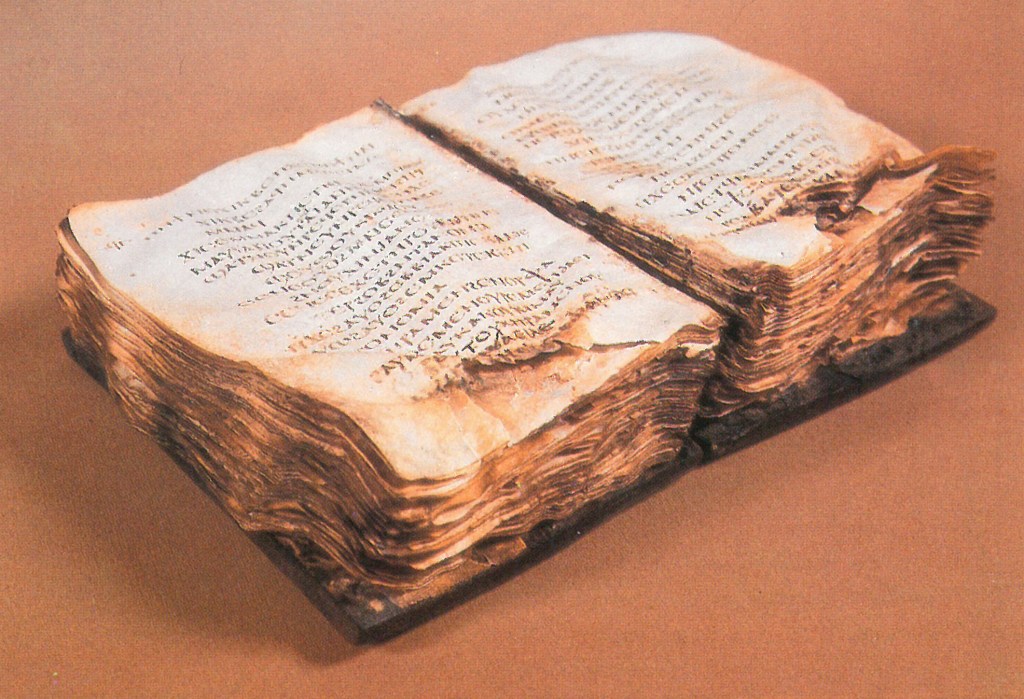

“A more recent discovery is less open to doubt but still frustratingly vague. In 1984, during excavations in a cemetery about forty-five kilometers north of Oxyrhynchus, a small but thick parchment codex of the Psalms in Coptic was reportedly discovered. The so-called Mudil Psalter (LDAB 107731) was likely copied in the fourth or fifth century. It is said to have been found either ‘under the head of a young girl’ or simply ‘near the head of a young girl’ in a tomb, or, most elaborately, ‘placed open as a pillow beneath the head of an adolescent girl in a humble cemetery.’1 The codex was found during work supervised by the Egyptian Antiquities Organization, but no analysis was undertaken on the human remains or other material in the tomb. Nor is there any photograph or drawing of this discovery showing either the corpse or the book in situ before removal. Thus we are left to wonder what was the exact relationship between the book and the corpse and what the date of the burial might have been.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, it is the most elaborate description of the find that has stuck, and this codex is sometimes thus called “the Pillow Psalter,” even though we don’t actually know how the codex was positioned in relation to the body. In any event, although the photo is a bit blurry, it looks like the book has undergone extensive treatment. Earlier images of the codex show the folia in a very cockled state:

It would be interesting to learn exactly what conservation procedures the codex has undergone.

The binding of the Mudil Psalter was the subject of an in-depth study published in 2020 by Julia Miller:

Julia Miller, “Modeling Ambiguity: The al-Mudil Codex (David Psalter),” in Julia Miller (ed.), Suave Mechanicals: Essays on the History of Bookbinding, vol. 6 (Ann Arbor: The Legacy Press, 2020), 305-362.

Miller’s study is full of excellent images of the codex and also Miller’s incredible models:

It’s nice to see the codex in the news and good to know that it is back on display at the Coptic Museum in Cairo.

For the first description, see Gawdat Gabra, “Zur Bedeutung des koptischen Psalmenbuches im oxyrhynchitischen Dialekt,” Göttinger Miszellen 93 (1986): 37–42, at 37. For the second, see Gawdat Gabra, Der Psalter im oxyrhynchitischen (mesokemischen/mittelägyptischen) Dialekt (Heidelberg: Heidelberger Orientverlag, 1995), 23. For the third, see Michelle P. Brown (ed.), In the Beginning: Bibles Before the Year 1000 (Washington, D.C.: Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, 2006), 74. Brown’s source for this more elaborate description is unclear. She cites Gawdat Gabra, Cairo: The Coptic Museum and Old Churches (Cairo: Egypt International, 1993), but Gabra here describes the book again only as having been found “in a shallow grave under a young girl’s head” (110). ↩︎

With Coptic this early, the dialect is important. This Psalter is in the Mesokemic dialect of Oxyrhynchus. I suspect that choice had some impact on how we have dated the MS; as Christianity becomes more monastic, Shenoute becomes more venerated, and texts will prefer his dialect which was Sahidic.

Pingback: The Upcoming Sale of the Crosby-Schøyen Codex (Just How Old is this Book?) | Variant Readings