Over the last few years, Candida Moss has published several very interesting articles on different aspects of slavery and early Christianity, such as:

- “The Secretary: Enslaved Workers, Stenography, and the Production of Early Christian Literature,” Journal of Theological Studies 74 (2023) 20-56.

- “Reading Between the Lines: Looking for the Contributions of Enslaved Literate Laborers in a Second Century Text.” Studies in Late Antiquity 5:3 (2021) 432-52.

- “Fashioning Mark: Early Christian Discussions about the Scribe and Status of the Second Gospel.” New Testament Studies 67:2 (2021) 181-204.

After reading these articles, I recognized that I was not going to be able to approach early Christian literature (or indeed, ancient Roman literature more generally) in quite the same way again. Gaining a greater appreciation of the the ubiquity of enslaved labor in the Roman world, and especially the role of shorthand specialists in the production of writing, casts all of early Christian literature in a different light.

Now Moss has synthesized her findings and produced what is probably the most important book in New Testament studies written in the last half century. God’s Ghostwriters: Enslaved Christians and the Making of the Bible manages to touch upon and reframe nearly every “classic” question of critical New Testament scholarship–issues of authorship and pseudepigraphy, sources and editing, transmission and textual variation, reading and reception, and even theology. And it’s written in a way that will be readable to those outside specialist circles (for scholars, a companion website provides amplified footnotes and a set of additional resources, and the articles mentioned above offer further documentation and nuance).

The topic of slavery in the New Testament is of course not new. There are many studies about what early Christian writers had to say on the topic of slavery and also about the metaphorical use of the language of slavery and freedom in early Christian writings. But in the last twenty years or so, scholarship has begun to focus more on actual enslaved people in the Roman world, including early Christians. Moss is meticulous in noting her debts to the work of predecessors and contemporary colleagues working on ancient slavery. Yet, she has pushed this conversation in interesting new directions by focusing especially on the role of literate enslaved laborers in the production, transmission, and consumption of literature in the Roman world.

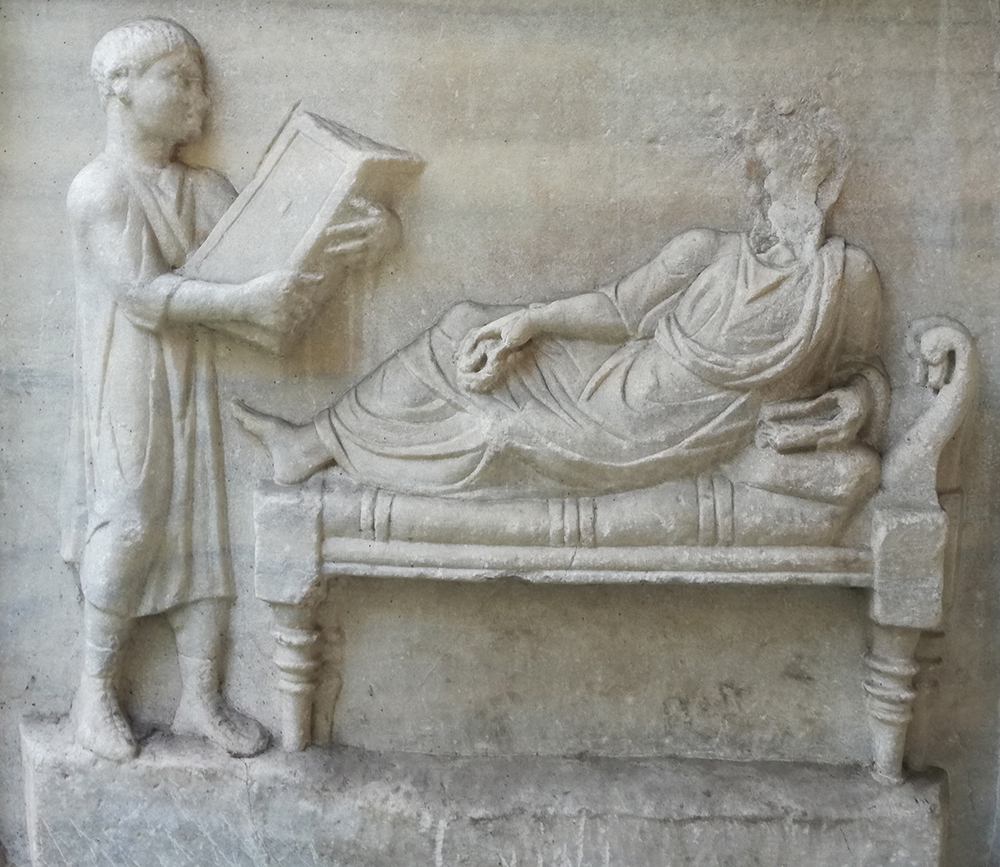

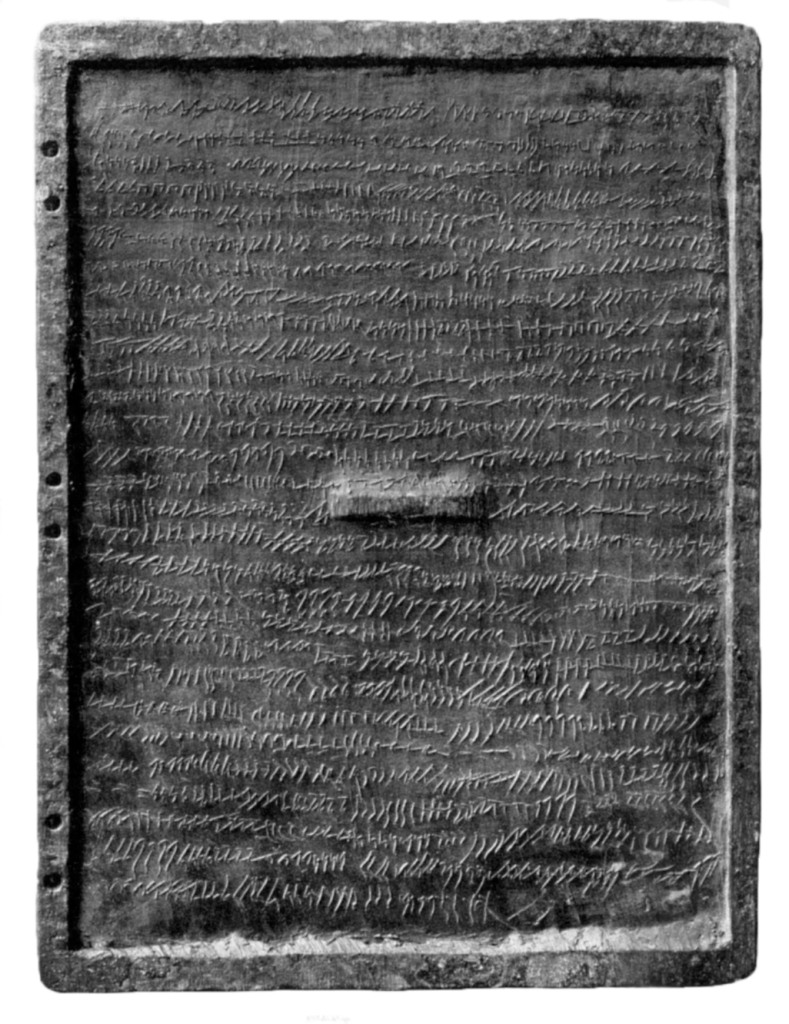

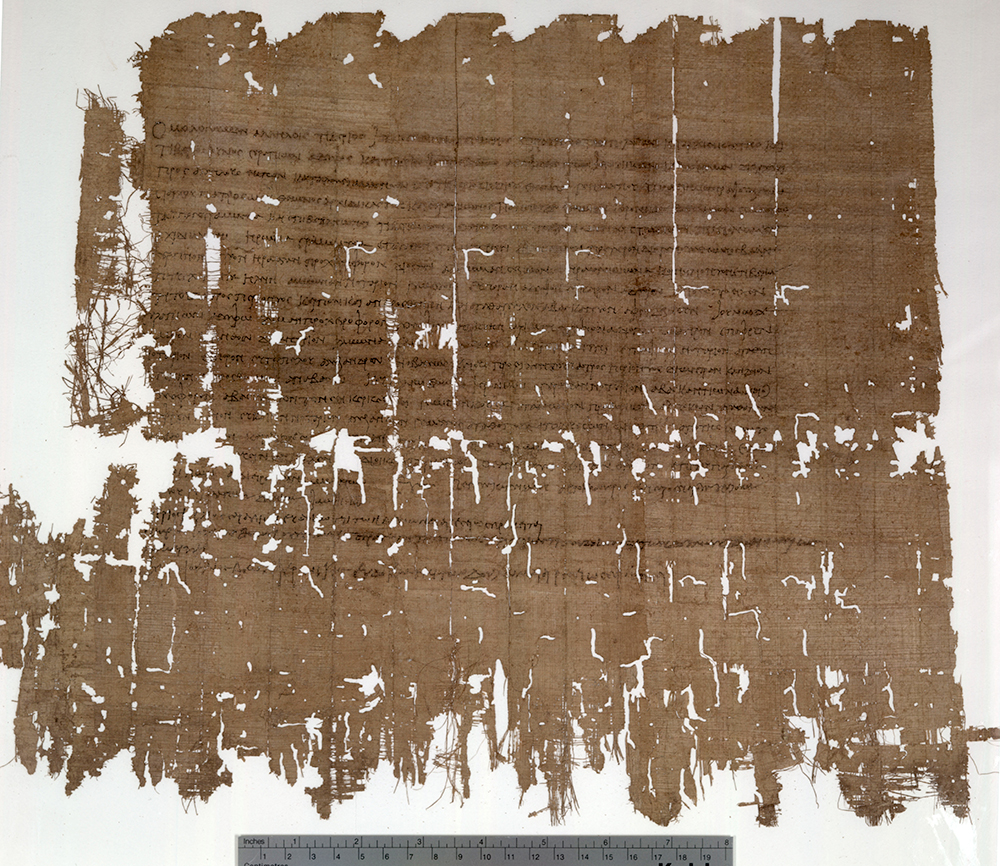

Part of what makes the book intriguing is the complication of the idea of authorship. When we talk about things like “Paul’s letters,” we’re actually talking about the letters of Paul and his co-authors. Several of the letters are clear about this in their opening lines: Paul and Sosthenes (1 Corinthians); Paul and Timothy (2 Corinthians, Philippians, and Philemon); Paul, Silvanus, and Timothy (1 Thessalonians). But Moss pushes further to highlight the different kinds of labor that went into composing writing in the Roman world. There are places in our sources where such labor flashes into view and then disappears just as quickly, such as Romans 16:22: “I, Tertius, the writer of this letter, greet you in the Lord.” We only see Tertius for a moment, but he has been there the whole time, “writing” the entire letter to the Romans. And acknowledging this fact feels different after reading Moss’s discussion of shorthand notation, a complicated set of signs memorized by literate workers, who were often enslaved, in order to quickly take dictation. The notary who took the dictation would later expand the shorthand copy to produce a copy in normal writing. It’s difficult to escape the conclusion that, much as we might like to imagine these letters as a direct conduit to “Paul’s beliefs,” what we are seeing here is more probably a situation of co-authorship. And it’s likely that Paul’s other letters, and most literary works in Roman antiquity, were written in a similar way. The praise of the shorthand writer attributed to the professor, poet, and statesman Ausonius evokes a partnership (albeit an unequal one): “No teaching ever gave you this gift, nor was ever any hand so quick at swift stenography: Nature endowed you so, and God gave you this gift to know beforehand what I would speak, and to intend the same that I intend” (Ephemeris 7).

Was Tertius enslaved? Moss demonstrates that people who performed secretarial work in Roman antiquity often were. And names like “Tertius” (literally, “the third one”) were common for slaves. But more elite Romans also had such “numerical” names. At the end of the day, we don’t know the status of Tertius with certainty; we simply don’t have enough data. Indeed, one of the themes that runs through the book is the problem of invisibility. Had Tertius not decided to add his ten words of greeting, we wouldn’t know he had ever existed. A similar situation applies with almost all literate enslaved labor in the ancient Roman world. We have to work with a small corpus of surviving evidence, because when these kinds of workers did their jobs well, they became invisible. Moss highlights the irony: “They performed their work so perfectly that they wrote themselves into nonexistence.”

One tactic Moss uses to address this problem of invisibility is to present historical reconstructions that are avowedly imaginative. This decision will no doubt invite some criticism. Yet, by explicitly and repeatedly highlighting the imaginative elements in her own account, Moss invites fellow historians to consider the imaginative work that lies behind many of our own easy assumptions about Roman literary culture.

The question really is: What should our “default” assumptions about the composition of early Christian literature be? Having read Moss’s work, I don’t think it’s historically responsible to picture Paul or the writers behind the gospels as lone theological geniuses. The realities of ancient practices of composition, at least to the extent that we can reconstruct and imagine them on the basis of limited and fragmentary sources, suggest that a rethinking of ancient authorship is going to be necessary.

And it’s not just the composition of early Christian literature that involved this often invisible labor. The copying of texts, the movement of books from place to place, and the reading of books all frequently involved enslaved or formerly enslaved workers. If Paul and co-authors wrote letters together, those who delivered letters also had a role in creating and conveying the meaning of the text. Cicero comments in a letter to a friend, “Your freedman Cilix was not well known to me before, but ever since he delivered me your letter, so full as it was of affection and kindness, he has himself by his own words followed up in a wonderful way the courtesy with which you wrote. It was a delight to me to hear him holding forth…” (Ad. fam. 3.1). Moss’s chapters detail the ways in which reading the ancient evidence with enslaved laborers in view can inform and transform the way we understand these aspects of early Christianity.

Clever and insightful observations abound. Throughout the book, Moss places various early Christian texts in dialogue with literature that depicts different aspects of ancient enslaved life. To take just one of many examples, Moss pairs Paul’s language–or perhaps better, the language of Paul, Sosthenes, and the others involved in the writing of 1 Corinthians–about the body (“Christ is the head of every man…You all are the body of Christ, and individually its limbs”) with the fascinating but neglected treatise on household management by Bryson, who theorized slavery for elite Romans: “Slaves resemble the limbs of the body…”

The comparison prompts reflections on how early followers of Jesus may have understood their relationship with the man they called their κύριος, dominus, master. It adds a dimension to the self-designation of some followers of Jesus as δοῦλοι Χριστοῦ, “slaves of Christ” (Romans 1:1, Philippians 1:1, Titus 1:1, James 1:1, 2 Peter 1:1, Jude 1). And for all the ink spilled on the meaning of πίστις/fides in early Christian writings, Moss’s emphasis on Roman elites’ use of the term to describe the proper attitude of the enslaved to the enslaver (“loyalty”) is striking and suggestive.

Overall, this book has an effect that is similar to that of E.P. Sanders’s Paul and Palestinian Judaism (1977). Even if you don’t agree with every interpretive move the author makes, the collective force of the book’s examples leaves you with what can only be described as a new perspective. In other words, if the field takes God’s Ghostwriters seriously (and it should), then there is no going back. And the way forward will involve greater effort to pay attention to the enslaved people who played important parts in producing, promulgating, and preserving the writing of the Roman world.

Inscription translation: Capture me, lest I escape, and return me to my master Viventius on the estate of Callistus; image source: The British Museum, 1975,0902.6

I’m not getting it. What is the new argument that scribes or co-senders had a greater role in composing the letters than is normally supposed? Have you read the work of Fulton, which shows that the role of co-senders was just to endorse the contents of the letters?

Thank you for the reference to Fulton–I have not read her work (I did a quick search and found a link to her thesis on your site that is no longer working, but I see it can be accessed at the Aberdeen Library site by searching “The phenomenon of co-senders in Ancient Greek letters and the Pauline Epistles”). I look forward to reading it. But to your question: What I find especially new and exciting about Moss’s recent articles and book is the uncovering of the work of secretaries and shorthand writers. Moss does a good job of demonstrating that the elite figures (Cicero, Pliny, etc.) whose surviving works constitute much of our evidence for Roman literary culture often play down the contributions of non-elite literate workers. Getting into what secretaries actually did involves getting into things like shorthand, and Moss’s survey of the evidence for this was really eye-opening for me. It raises all sorts of questions about the levels of input that these unmentioned workers may have had in all of Roman literature. The JTS article on secretaries linked at the top of the post gets into this in some detail.

Is there an exegetical pay-off?

Yes, in the sense that there are a number of passages that read quite differently (the story in Mark 2:1-12 and the textual problem in Romans 5:1 are a couple of her examples in the book), but to me, what sets the book apart is that it reframes the traditional goals of exegesis–moving away from a simple singular author-to-reader(s) model and recognizing the various other agents involved at all phases of the production and reception of literature.

I see. So the scribes in Mark 2:1-12 did not have ears to hear. They had ears to take short-hand to use against Jesus. Right?

Metzger discussed the role of Tertius in Rom 5:1. Similarly, I have suggested that Euodia was, for Paul, Ευωδια, with an omega, arguing that she was Lydia renamed.

Pingback: Biblical Studies Carnival # 217 – April 2024 – The Amateur Exegete