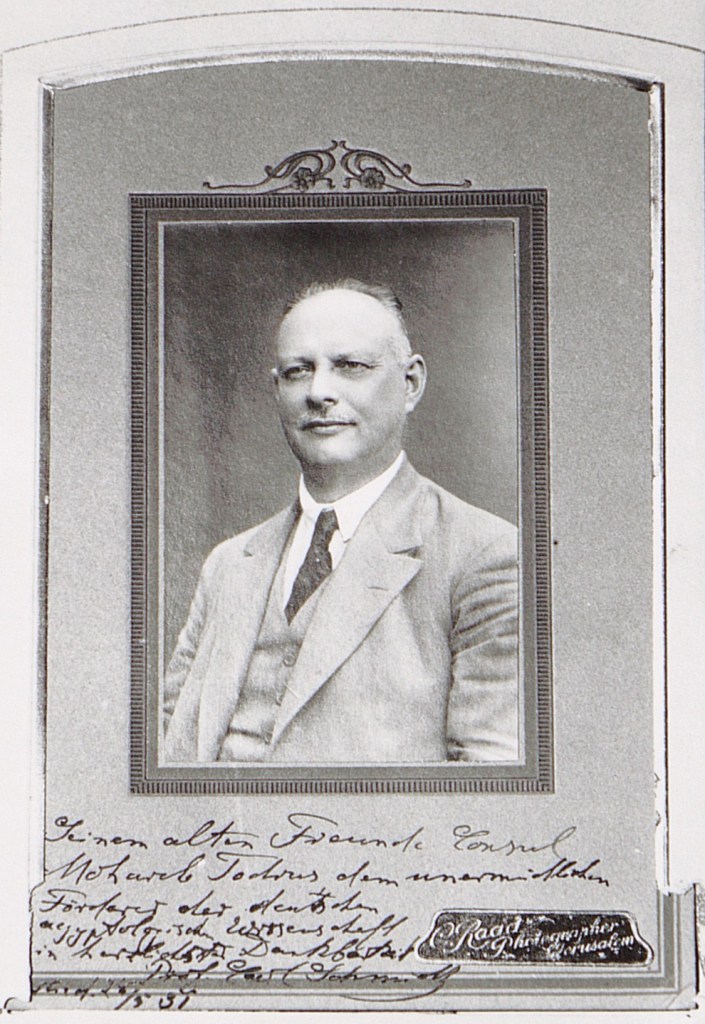

The coptologist Carl Schmidt (1868-1938) was very active in the antiquities trade. His name is associated with the purchase of many well known manuscripts, including one I’ve discussed here.

image source: Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Bremen

An important new article on Schmidt has appeared in a journal that may not be on the radar of papyrologists:

- Jakob Wigand, “Unearthed, Smuggled and Decontextualized: Carl Schmidt and the Provenance of Hamburg’s Papyrus Bilinguis 1,” Philological Encounters 9 (2024) 1-37

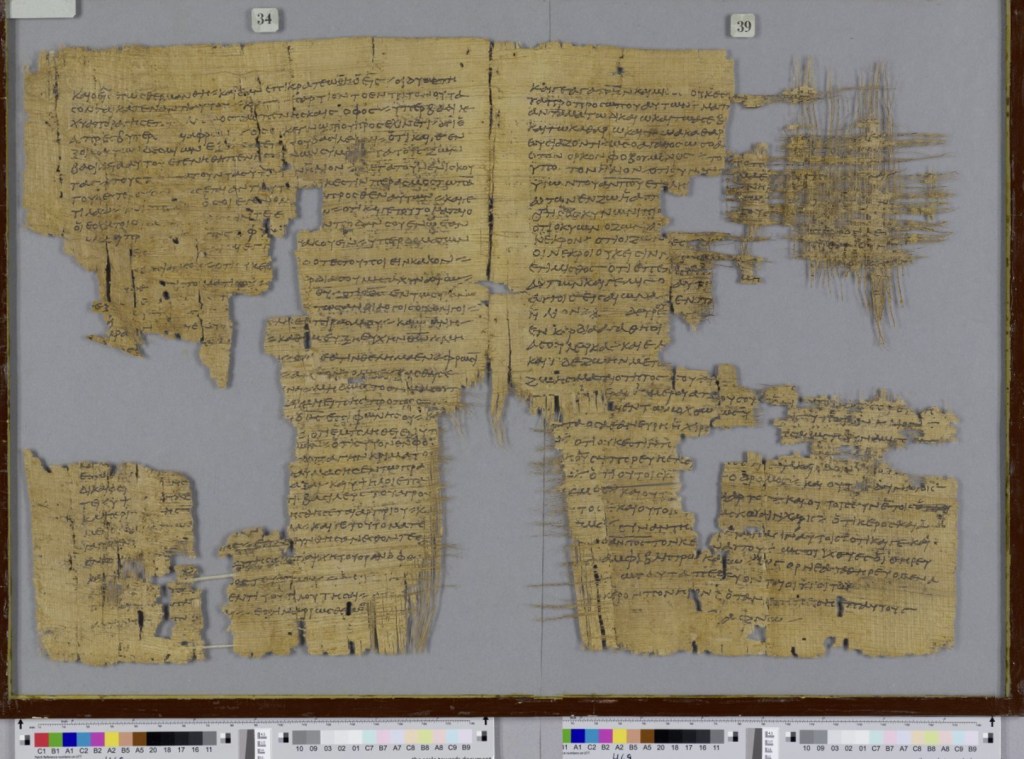

Using archival evidence from the Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Hamburg, Wigand unpacks the exact nature of Schmidt’s involvement in the purchasing and export of papyri. Wigand’s main example is the documentation for the purchase of the Hamburg bilingual codex (TM 61979), which was obtained by Schmidt in the late 1920s.

Wigand’s thorough investigation uncovers both a previously unknown story of the alleged archaeological context of the codex and details about the logistics of Schmidt’s removal of the codex from Egypt. The most important finding is a letter from Schmidt that clearly shows he intentionally avoided the inspection required by Egypt’s Law No. 14 of 1912 on Antiquities, which prohibited the export of antiquities without the authorization of the Antiquities Service. Wigand also demonstrates that this was not an isolated case for Schmidt.

Articles like this are very useful because they add important texture to the way we approach the antiquities trade before the 1970s. Many conversations about the illicit trade in antiquities are oriented around the 1970 UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property. Sometimes these discussions can leave the impression that any material that can be shown to have left its country of origin before 1970 is “clean” and that worrying about pre-1970 smuggling amounts to unfairly judging our predecessors by our own modern standards. But national laws concerning antiquities existed well before 1970. So, to point out that this material was smuggled is not to anachronistically condemn our forebearers, but instead to acknowledge that some of our academic ancestors engaged in activity that was criminal even in their own day.

Yet, archival studies of the histories of manuscript collections can also complicate another assumption–that all papyri that appeared on the antiquities market in the early part of the twentieth century were illicitly smuggled out of Egypt. For instance, Lorne Zelyck’s detective work at the British Library uncovered the envelope in which the fragments of the Egerton Gospel were shipped to London. The envelope from Maurice Nahman still carries the intact red seals of the Egyptian Museum, indicating that the papyri in this shipment were inspected and approved for export by Egyptian authorities.1

No doubt more such evidence, both explicit evidence of smuggling and explicit evidence of legal export, could be uncovered with further study. We need (much) more of this kind of archival research.

- Lorne R. Zelyck, The Egerton Gospel (Egerton Papyrus 2 + Papyrus Köln VI 255): Introduction, Critical Edition, and Commentary (Leiden: Brill, 2019), 20, note 22. ↩︎