Over at his blog, Bart Ehrman has been posting some basic facts about different books of the New Testament. The last couple posts have been about the Gospel According to Mark, and yesterday’s post, which is publicly available, treats the question of the title of the Gospel According to Mark, and includes a short discussion of how the title shows up in our earliest complete manuscripts of Mark. Ehrman writes [[Update 28 January 2025: Ehrman has now adjusted the text of his post.]]:

“Our oldest two manuscripts (Sinaiticus and Vaticanus, for you fellow Bible nerds) come from toward the end of the fourth century (around 375 CE), and they have the shortest titles (“According to Mark”). But in both cases, the titles were added by a later scribe (in a different hand). We don’t really know how much later. So it’s impossible to know when the manuscripts began calling it this, except to say that the manuscripts that the authors of both these 4th century manuscripts used apparently didn’t have titles at all (since they lacked them until the later scribe added them). Interesting.”

But is this actually right? On papyrus rolls, titles typically appeared at the end of the text, and this practice carried over into codices. In the case of Codex Sinaiticus, the titles that appear at the ends of the works are widely regarded to be the product of the original copyists of the books. Here is what Milne and Skeat say in their detailed study of the codex:

“That those main titles are written by the same scribe as the immediately preceding text has never been doubted, and is so obvious from the most cursory inspection of the manuscript that it needs no justification here.”1

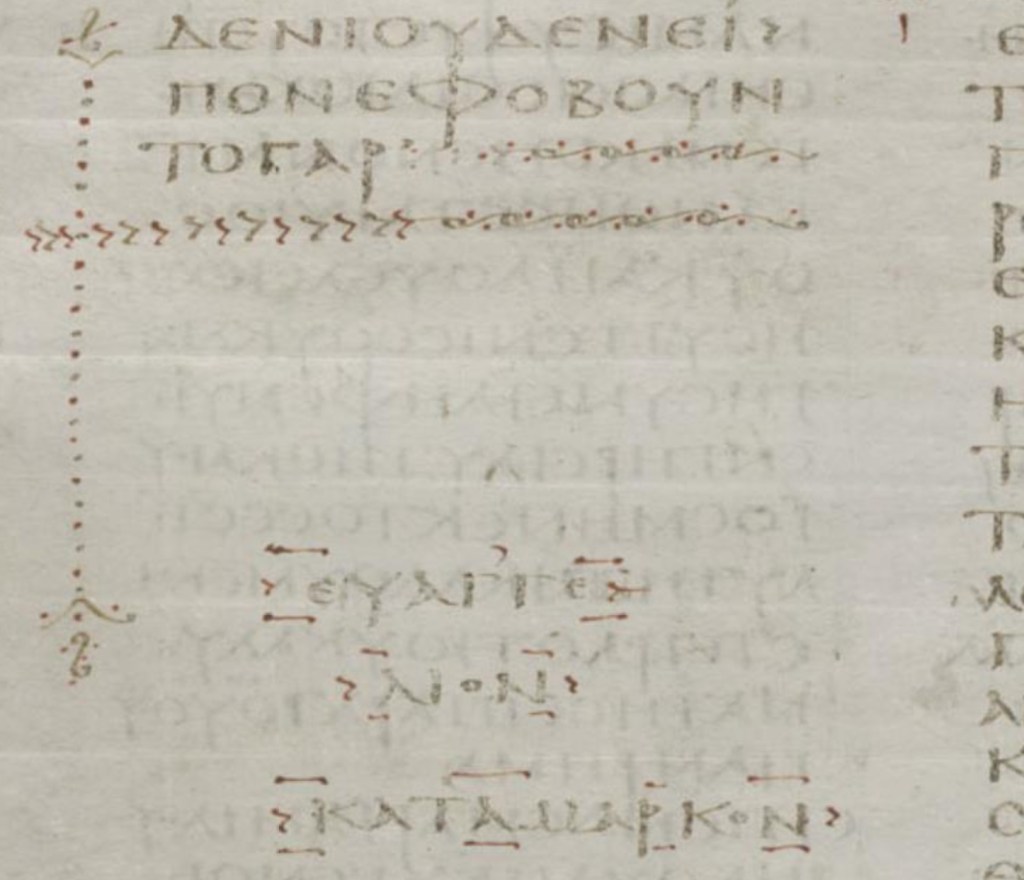

And in fact, the subscript title at the end of Mark in Codex Sinaiticus is not the short version but the longer version (ⲉⲩⲁⲅ’ⲅⲉⲗⲓⲟⲛ ⲕⲁⲧⲁ ⲙⲁⲣⲕⲟⲛ):

Some aspects of the script differ from that of the main text (the smaller epsilon and omicron raised off the base line, the mu with a curved belly), but other letters are identical with the script of the main text of Mark. There is no reason to doubt that these titles were part of the original production of the manuscript and that the differences in the script are simply decorative.

There are running titles (titles at the top of each page) in the gospels in Codex Sinaiticus that use the shorter version of the title, just ⲕⲁⲧⲁ ⲙⲁⲣⲕⲟⲛ, but these too are generally thought to be the work of the original copyists of the codex.

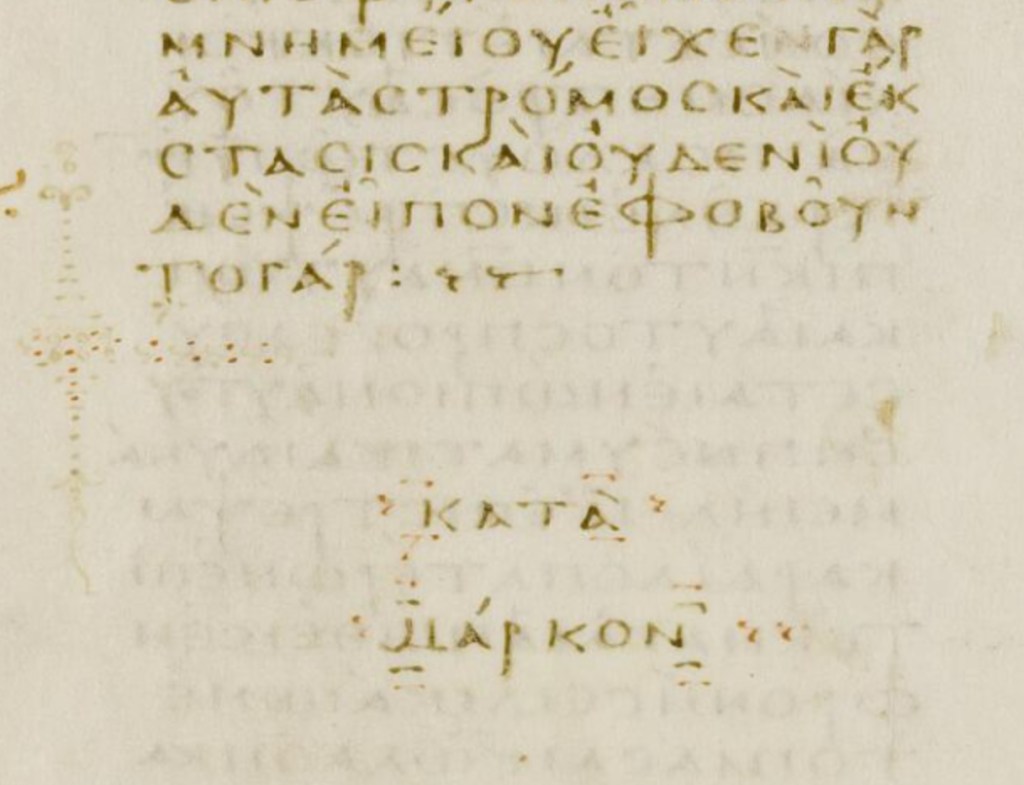

What about Codex Vaticanus? Here, we do indeed find the shorter version of the title at the end of Mark:

But was this title a later addition or the work of the original producers of the codex? In this case, it’s a little harder to tell because almost all the letters in this codex have been re-inked by someone who was not as skilled as the original copyists at producing the biblical majuscule script. But again, the consensus view is that these end titles were the work of the copyists who produced the codex.

In a similar fashion to Codex Sinaiticus, Codex Vaticanus has running titles that use the shorter version of the title (ⲕⲁⲧⲁ ⲙⲁⲣⲕⲟⲛ), but these are also generally thought to have been added as a part of the production of the codex (and in fact, they constitute important evidence for the original script of the book because they have not been re-inked for the most part).

So, to summarize: The titles of the gospels in Codex Sinaiticus and Codex Vaticanus were most likely the work of the original producers of these books [codices] and attest to the use of both the longer version of the title (ⲉⲩⲁⲅⲅⲉⲗⲓⲟⲛ ⲕⲁⲧⲁ ⲙⲁⲣⲕⲟⲛ in Codex Sinaiticus) and the shorter version (ⲕⲁⲧⲁ ⲙⲁⲣⲕⲟⲛ in Codex Vaticanus) at the time when these books [codices] were produced.

- H.J.M. Milne and T.C. Skeat, Scribes and Correctors of the Codex Sinaiticus (London: The British Museum , 1938), 27 ↩︎

Seems Ireneaous (about 175 AD) identified it as Mark’s Gospel.

Thanks–yes, Ehrman notes this point in his post: “In his work Against Heresies, from 180 CE or so, Irenaeus names the book Mark and quotes it, so we know he’s talking about our Mark.” I’m just emphasizing that Codex Sinaiticus and Codex Vaticanus do have titles for the gospels and that they are not later additions (at least according to the consensus view).

Thanks for your post. I am interested in the topic of headings, titles, and the like. Can you say more about the point you made that if the handwriting of the title and the text are the same in a 4th cent MS, then the title is original to the work several centuries before? Did I misunderstand?

Yours, Simi Chavel

Thanks for the comment. All I’m saying here is that the end titles are original to these two manuscripts. Whether the title was part of the work as composed is a separate question. In the case of the gospels, we don’t know whether the titles circulated with them from the beginning. The titles of the gospels are very strange in the context of ancient Greek literature. Ascribing authorship typically took the form of the author’s name in the genitive case and then the title of the work in the nominative (or other formulations with prepositions, like περι ψυχης). The formulation ευαγγελιον κατα + name-in-the-accusative-case, is not a common way of attributing a title and author in ancient Greek.

That tracks, as the Zeds say. Thanks for clarifying and elaborating.

Yours, Simi Chavel

Hi, We ought to include the Codex Alexandrinus (A) in this discussion which can be seen in CSNTM Image Id: 143488 / CSNTM Image Name: GA_02_0646b.jpg at https://manuscripts.csntm.org/manuscript/View/GA_02 where the longer version of the title ⲉⲩⲁⲅⲅⲉⲗⲓⲟⲛ ⲕⲁⲧⲁ ⲙⲁⲣⲕⲟⲛ also appears. Correct me if I am wrong but in the 1800s the A was considered older than both Vaticanus (B) and the later Sinaiticus (א). The order based on age of the codices appears to have changed after the Sinaiticus was introduced.

Pre end 1800s 1.Alexandrinus 2.Vaticanus 3.Codex Ephraemi Rescriptus

Post end 1800s 1.Sinaiticus 2.Vaticanus 3.Alexandrinus 4.Ephraemi Rescriptus

Happy to receive comment on true order based on age. I think the Alexandrinus ought to be restored to its original position. I understand also there was some controversy surrounding the Sinaiticus at the time in the mid 1800s and following.

Regards Alex

Thanks, Alex. Fortunately, Codex Alexandrinus appears to have a reasonably good terminus post quem in the form of the Epistle of Athanasius (d. 373) to Marcellinus, which seems to have been written relatively late in the career of Athanasius (ca. 360-365), but I think most scholars place Alexandrinus in the fifth century, while preferring a fourth century date for Vaticanus and Sinaiticus.

Hi Brent, Note from Wikipedia “Wettstein announced in his Prolegomena ad Novi Testamenti Graeci (1730) that Codex A is the oldest and the best manuscript of the New Testament, and should be the basis in every reconstruction of the New Testament text.[44] Codex Alexandrinus became a basis for criticizing the Textus Receptus (Wettstein, Woide, Griesbach).”

The thing that bugs me is that often the A is spoken in terms of its NT portion without regards to its OT portion of the same age. Definitively the LXX of A held number 1 position over the LXX B before the controversial Sinaiticus later came along. It may be the case that scholars with certain biases then reordered the list.

Nice to point this out Brent. I just echoed at The Text of the Gospels.

You mentioned that titles of scrolls tended to be at the ends. Does this mean that they stored scrolls with the ends on the outsides so that the titles could be easily accessed? I think you may have pointed to conflicting evidence on this.

Yes, typically in rolls, titles were at the end, but they also sometimes appear at the beginning before the text or even on the outside of the roll. For storage, the typical device for identifying and accessing rolls was the index tag (which I briefly discussed here: Storing Scrolls).

Thanks.

Is there any scholarly consensus about the relationship between gMark and gMarcion?

I would say that up until recently (the last 10-15 years), the vast consensus was the Marcion’s gospel was derivative from the synoptics (Luke in particular), but there are a growing number of scholars who argue that this relationship (presumed by the church fathers) needs to be reevaluated. See recent work by Markus Vinzent, Matthias Klinghardt, and Jason BeDuhn. My sense is that theirs is currently a minority view, but people seem open to considering their arguments.

Thank you. I’ll look those up.

Dear Prof. Nongbri,

Thank you for addressing the subscriptio! My question is: What about the inscriptio at the beginning of the Gospel? According to the ECM, the first hand of Sinaiticus and of Vaticanus omitted the title (01*. 03*), while the correctors included it (01C1. 03C1). Ehrman’s quoted assertion is wrong regarding the subscriptio, but it is right regarding the ECM’s and the NA28’s interpretation of the inscriptio: “the titles were added by a later scribe (in a different hand)” is exactly what these editions would imply. It seems to me that the title of the Gospel was there in the first hands at the end of the Gospel, and a later hand added it also at the beginning – this seems to be the theory of the editors. What do you think?

Kind regards,

Zacharias Shoukry

Thanks for your comment. First, with regard to Codex Sinaiticus: Tischendorf considered the superscript title as the work of Scribe D. Lake agreed. Milne and Skeat also agreed but suggested that the title was added by Scribe D after the main text was copied. So, nobody who has closely studied the codex thinks that “a later scribe” added the superscript title; everyone regards it as the word of Scribe D, but Milne and Skeat suggested that Scribe D added it after the main text was copied (I am unsure why they believed this).

With regard to Codex Vaticanus: Versace considered the superscript titles as contemporary with the production of the codex (“Nello stesso momento in cui il testo veniva copiato, al principio e alla fine dei vari libri furono scritti i titoli”). So again, the most careful student of the codex does not regard the superscript title as the work of a later scribe.

I think the confusion results from a misunderstanding of the idea of what a “corrector” is for Nestle-Aland. For instance, note that in Nestle-Aland 28, B1 is said to be “roughly contemporaneous with B” (p. 59*). That is to say, a “corrector” is not always “later” and may in fact be the same the very same person who copied the manuscript. Nestle-Aland 28 makes this point clear when the symbol “c” is defined in this way: “identifies a correction made by a later hand, but sometimes also by the first hand.” I think sometimes people do not register the point in bold, and this may have been what happened to Prof. Ehrman.