It is common for historians of ancient Rome to state that writers did not use desks (As Theodor Birt put it, “In antiquity, people did not write on desks”).1 I have noted before on the blog that I am not sure this view is entirely accurate. In a well-known article, Bruce Metzger gathered some visual evidence for the use of desks in Late Antiquity, a relief from Ostia Antica, a relief from Portus, and a mosaic from Thabraca that all show writers at desks.

Another aspect of the discussion is the material evidence of so-called scriptoria in the Roman world. The most famous of these is a controversial room found in the ruins of Qumran. Another (the only other?) potential surviving example is a structure in the remains of a Roman military camp at Bu Njem in modern Libya.

The site was excavated between 1967 and 1980 by a team led by René Rebuffat (1930-2019). According to the excavators, the fort was established in 201 CE and used by Roman military garrisons until around 260 CE. It was occupied by squatters after that who left a few traces and then abandoned and buried by wind-swept sand. The fort thus survived to the present in remarkably good condition.

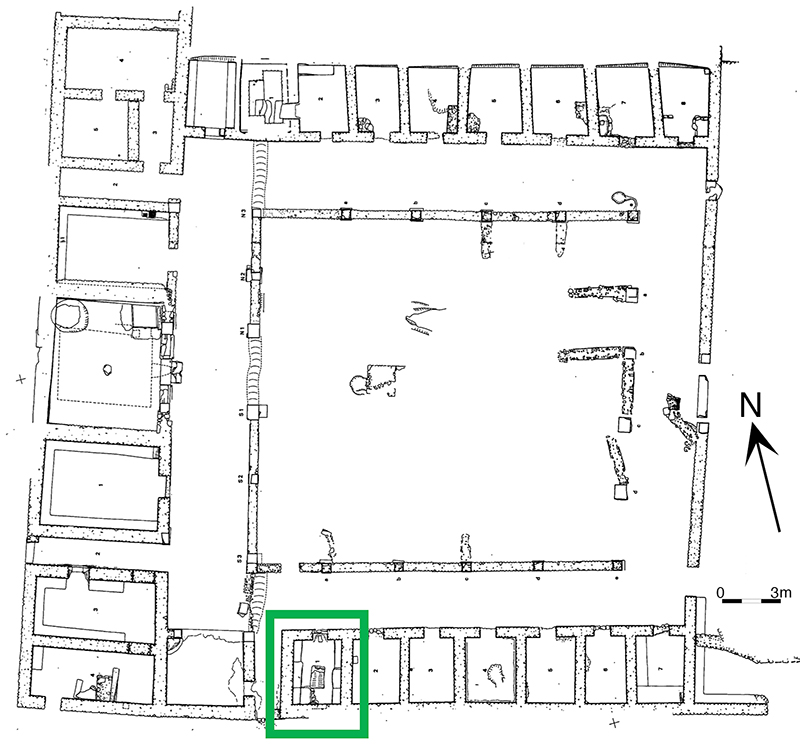

Among the discoveries at the site in 1971 was a space on the south side of the central facility contained benches along the walls and a raised rectangular block (un massif rectangulaire) in the center of the room, highlighted in green in the image:

The excavators described this space as “a scriptorium” that existed in two phases. In the first phase that corresponds to the construction of the fort in 201, the room featured a flat rectangular table (109 cm long, 66 cm wide, about 60 cm high) and two short benches on either side of the table (the report describes the benches as 80 cm high, but this must be an error; the scale indicates they are about 40 cm high). In a second phase, additional benches were added to extend to the north and south walls on both sides of the room, and a triangular “lectern” (pupitre), about 10 cm high at its peak, was added to the top of the flat table. The authors provided a top plan and profile drawing of the area as they found it:

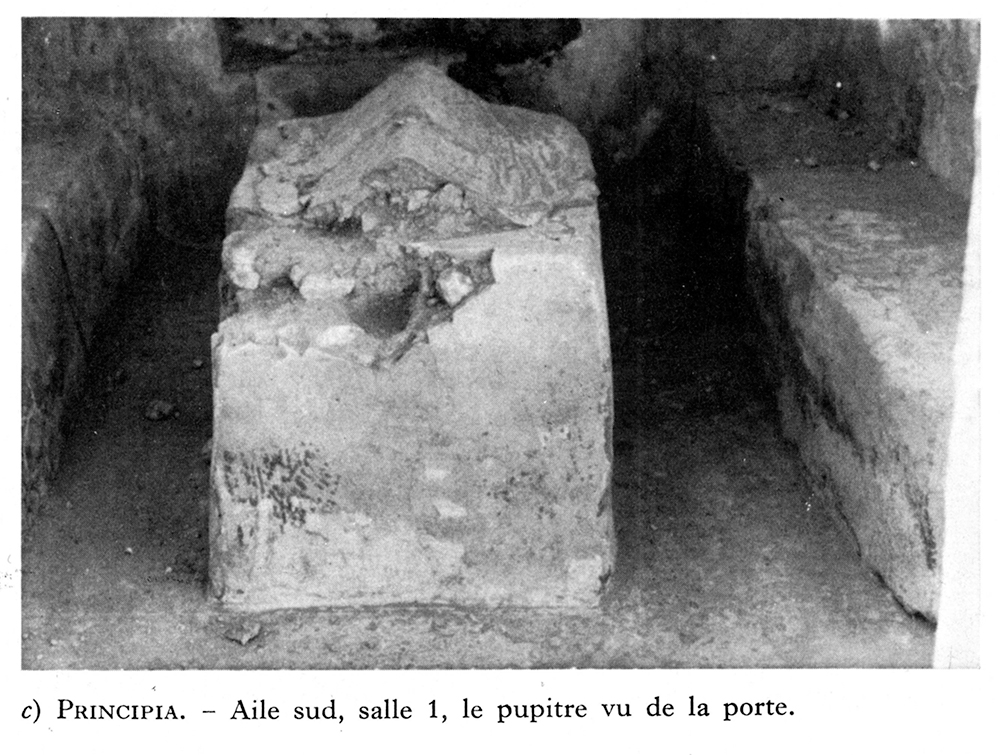

The sloping triangular feature in the profile drawing would be the “lectern.” The dark grey feature above it represents a niche in the south wall that is also visible in dotted lines in the top plan above. The “lectern” was somewhat damaged when the excavators found it, as illustrated in a photo that accompanied the article:

The excavators describe the use of the room in the following way:

“The central block of the Bu Njem scriptorium is not a table but a double-sloped lectern (pupitre). It is likely that the flat table (built in 201) that preceded this development also served as a lectern, because it was much too low, and the slightest test shows the discomfort of the position to which it would have forced a writer. The position remained uncomfortable with the double-sloped lectern, and the extension of the benches shows that one could work without being in front of the block. These benches are not designed for squatting or kneeling: They were obviously set up so that a seated person can be comfortable, and their extension beyond the block also proves that they are not made to raise a kneeling or squatting person in front of the block. The only overall hypothesis is therefore that the lectern served to support documents being read by a reader and listened to by other people sitting on the benches. The reader could naturally write on his lap while reading, and the listeners could also write. The room then fully deserved the convenient name of ‘scriptorium’ that we have given it.”2

The excavators paint an interesting picture here, one in which the “desk” is not used for writing but for holding something in position for reading. The excavators seem to be describing the production of multiple copies of a text by dictation, but what sort of writing do they imagine is happening in this military setting? The written artifacts found at the site included more than 146 ostraca that date from near the end of the occupation of the site, ca. 250-260 CE, and the majority of which were found in the vicinity of the so-called scriptorium.3 But these are mostly daily reports, not really the kind of thing needed in multiple copies. There are inscriptions of a literary nature that have survived at the site, namely poems inscribed on stone and credited to two centurions.4 But again, drafts for inscriptions probably wouldn’t be needed in multiple copies. I’m not sure what kind of texts the excavators have in mind with this imagined scene of dictation.

So, this is a very interesting piece of evidence, but I’m unsure about the proposed use of this space. I think there is more to say, but the bibliography on this “scriptorium” seems very limited. I would be grateful for any tips on other relevant publications on this space. For a good recent overview of the study of Bu Njem, see Anna H. Walas, “New Perspectives on the Roman Military Base at Bu Njem,” Libyan Studies 53 (2022) 48-60.

- Theodor Birt, Die Buchrolle in der Kunst (Leipzig: Teubner, 1907), p. 209: “Im Altertum schrieb man nicht auf Pulten.” ↩︎

- “…le massif central du scriptorium de Bu Njem n’est pa un table, mai un pupitre à double pente. Il est probable que la table, plate qui a précédé cet aménagement et qui a été construite en 201, servait aussi de pupitre, car elle était beaucoup trop basse, et Ie moindre essai montre l’inconfort de la position à laquelle elle aurait contraint le scripteur. La position restait inconfortable avec le pupitre à double pente, et l’extension des banquettes montre qu’on pouvait travailler sans être en face du massif. Ces banquettes ne sont pas faite pour s’accroupir ou s’agenouiller: elles ont visiblement été réglées pour qu’un homme assis soit confortablement installé, et leur prolongation au-delà du massif est également bien la preuve qu’elles ne sont pa faite pour exhausser un homme agenouillé ou accroupi en face du massif. La seule hypothèse d’ensemble est donc que le pupitre servait à supporter des documents qu’un lecteur, lisait, et que d’autres personnage assis sur le banquettes écoutaient. Le lecteur pouvait naturellement écrire sur ses genoux en même temps qu’il lisait, et les auditeurs en tout cas écrire eux aussi. La salle méritait alors pleinement le nom commode de ‘scriptorium’ que nous lui avons donné d’abord.” ↩︎

- See Robert Marichal, Les ostraca de Bu Njem (Tripoli, 1992). Marchial published 146 ostraca, but he prepared others for publication, including alphabetic exercises, that have not yet been fully published. See the discussion here. ↩︎

- See J.N. Adams, “The Poets of Bu Njem,” Journal of Roman Studies 89 (1999) 109-134. ↩︎

Maybe marginally relevant is my fallible recall of a lecture by Richard Janko (U. Michigan) on Herculaneum at Duke U. on Feb. 24. He suggested that one excavated room that includes a curved wall was used for lecturing. And, here I’m less certain: because there is at least one example of more than one copy of a text, it might have been mentioned that further excavation–should that happen–could likely find a scriptorium. And if that isn’t conditional enough, I’ll add that the proposal that the Qumran scriptorium was a triclinium has not weathered well.

Thanks–Herculaneum is an interesting case because it’s a place where we have some wooden furniture preserved. I suspect from the iconography that desks in many places in the ancient Mediterranean world were made of perishable materials, and so have not survived in the archaeological record. I’m not aware of anything there that has been definitively identified as a desk at Herculaneum, but, as you say, further excavation there has the potential to offer some new evidence.

The phrase “so-called scriptorium” and the weak criticism of the Qumran scriptorium remind me of the question of what constitutes a scriptorium.

Alan H. Gardiner, in “The House of Life,” Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 24, No. 2 (Dec., 1938), pp. 157-179, used the term scriptorium.

The place I’d look first is Konrad Stauner’s Das offizielle Schriftwesen des römischen Heeres von Augustus bis Gallienus: Eine Untersuchung zu Struktur, Funktion und Bedeutung der offiziellen militärischen Verwaltungsdokumentation und zu deren Schreibern (Bonn 2004). It’s a fantastic discussion and corpus of relevant documents relating to writing in the Roman army. There is even attestation of an official legionary orthographus (proofreader? grammar stickler?). I don’t see scriptorium in Stauner’s index, but tabellarium is very often discussed. Which makes me wonder: if it is a scriptorium at Bu Njem, shouldn’t we expect evidence for document storage nearby?