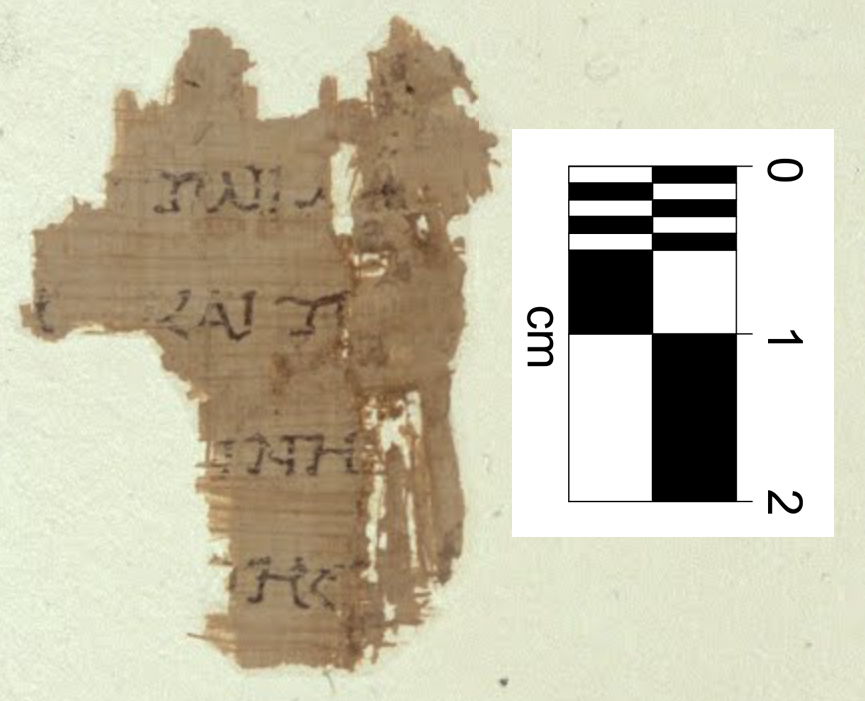

I have written before about 7Q5, a small fragment of papyrus found in Cave 7Q at Qumran. It contains an unidentified text in Greek. It became (in)famous in the early 1970s when José O’Callaghan (1922-2001) argued that it preserved a bit of the Gospel According to Mark (Mark 6:52-53). Crucial to this identification was the reading of line 2. The original editors had read the Greek letters tau, omega, iota, and alpha, ⲧⲱⲓ ⲁ̣. O’Callaghan saw instead tau, omega, and the remains of a very oddly shaped Greek letter nu, ⲧⲱⲛ.

I say “oddly shaped” because construing the existing traces of ink in line 2 as a nu would result in a letter substantially different from the clear letter nu that occurs in line 4 of 7Q5.

For this and other reasons, O’Callaghan’s argument did not prove persuasive to most scholars.1 His argument has, however, lived on among some enthusiastic supporters.

In an another post, I noted that those in favor of the identification of 7Q5 as Mark often invoke names of authorities who have at one time or another agreed with O’Callaghan. Figuring out what these authoritative voices actually said, however, is often challenging, as the advocates almost never cite arguments but instead just list names. So, over the last year, I have been tracking down some of these references. In my earlier post, I looked into what the papyrologist Orsolina Montevecchi (1911-2009) had to say about 7Q5. It turned out that she added nothing substantial to the discussion and in fact obscured matters by ignoring the key point (O’Callaghan’s readings of certain letters are not really possible given the ink on the page). In this post, I will examine the contribution of another authority whose name frequently comes up in these discussions.

Carsten Thiede (1952-2004), perhaps the most vocal promoter of O’Callaghan’s interpretation of 7Q5, frequently brought up the name of Herbert Hunger in support of O’Callaghan: “A classical papyrologist like Herbert Hunger, with no vested ‘theological’ interest either for or against the proposed New Testament passage, accepted the nu without the slightest hesitation.”2 This is interesting. Hunger was a scholar with a formidable reputation–What did he actually say in connection to 7Q5?

Herbert Hunger (1914-2000) is primarily remembered as a Byzantinist, but early in his career, he also had responsibility for the large collection of papyri in the Austrian National Library for a period of six years (1956 to 1962). During this stretch of time, he produced a booklet on the Vienna collection as well as editions of several Vienna papyri (17 pieces by my count, but I may be missing some).3 And in 1961, he published a short article on P.Bodmer 2 that attempted to redate that manuscript of John’s gospel from the early third century to the first half of the second century, an effort that received a mixed reception.4

In 1962, Hunger was appointed as Ordinariat für Byzantinistik at the University of Vienna and left behind the papyrus collection. Hunger held this position in Byzantine Studies for over twenty years. During that period, he was a prolific scholar, initiated many long-term research projects, and became widely known and respected in the world of Byzantine Studies. He was honored with multiple Festschriften by his colleagues and received several honorary degrees.

In a book published in 1992 (seven years after his retirement from the chair in Byzantine Studies in 1985), Hunger reclaimed the title of “papyrologist” and authored a chapter in support of Carsten Thiede’s identification of 7Q5 as a copy of Mark. The title of his contribution was “7Q5: Markus 6,52-53 – oder? Die Meinung des Papyrologen.”5

Unlike Montevecchi, Hunger did make a new argument in support of Thiede’s (and O’Callaghan’s) contested readings of letters in 7Q5. Hunger began his chapter by criticizing the appearance of the script of 7Q5, describing it as “below average” (unterdurchschnittlich) and even going so far as to call it the product of a βραδέως γράφων, a “slow writer,” that is, a person just (barely) capable of writing their own name and a short statement on a document.6

Hunger then offered comparisons between the letters in 7Q5 and the letters in two other pieces that have examples of less-than-competent writing: the student hand in the famous wax tablet at the British Library (Add. MS. 34186) and the signator’s hand in P.Vindob. inv. G 02001.

In connection with the wax tablet, Hunger saw similarities between the sigma, eta, and nu of the student hand and the hand of 7Q5.

in P.Vindob. inv. G 02001, Hunger pointed to the alpha and omega as being similar those letters in 7Q5.

In these comparisons, Hunger also focused especially on forms of the letter nu, arguing that the scribe of 7Q5 was not an experienced writer and may thus have written the same letter in very different and even non-standard ways.

Up to this point the argument is comprehensible. I disagree with Hunger’s assessment (there is nothing about the script of 7Q5 that suggests the writer was incompetent), but thus far, Hunger’s argument is at least intelligible.

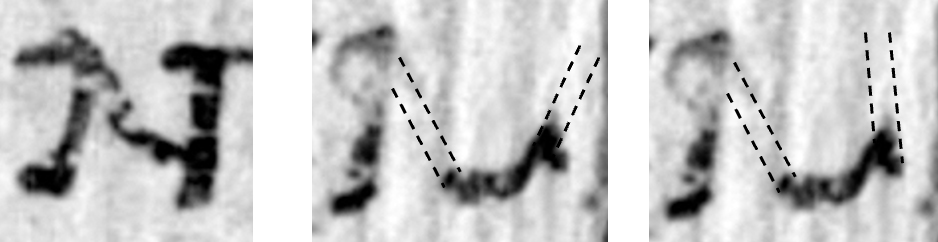

But then Hunger very abruptly and without comment begins a hunt through palaeographic handbooks and the Vienna papyrus collection in search of forms of the letter nu that might somehow fit with the visible bits of ink in line 2 of 7Q5. That is to say, rather than continuing the argument about incompetent writers, Hunger turns to alleged parallels from perfectly competent writers, which makes no sense in terms of his larger argument. To make matters worse, his suggested parallels do not really resemble the oddly shaped nu that O’Callaghan’s proposal demands. I offer just one of Hunger’s examples drawn from Seider’s palaeogrgaphic handbook, Seider II, plate 45 (that is, the Chester Beatty Ezekiel-Daniel-Esther codex):

Hunger claimed the nu in the Beatty papyrus showed the same “diagonal oscillation” (diagonale Schwingung) of the supposed nu in line 2 of 7Q5. But there is no real similarity; the nu in the Beatty papyrus is formed in a perfectly normal manner. It will not be helpful to work through any more comparisons because Hunger’s approach involves piling up irrelevant palaeographic comparanda in order to give the impression of having a solid argument. In fact, it is all a house of cards (incidentally, this is also the approach that Hunger took in his article on P.Bodmer 2).

To confuse matters further, Hunger turned to an article by J.P. Gumbert, “Structure and Forms of the Letter ν in Greek Documentary Papyri: Α Palaeographical Study,” Papyrologica Lugduno-Batava 14 (1965), 1-9. From Gumbert’s chart of documentary forms (which, to be completely clear, tracks forms produced by competent writers of documentary texts–that is the whole point of his study). Hunger suggested that the (supposedly incompetent) writer of a literary text in 7Q5 was trying to produce a very particular documentary form of nu, marked with a red arrow in the Gumbert’s chart below:

With this alleged parallel, Hunger believed he had clinched his argument:

“The Urform to which the disputed nu in line 2 can be traced is found in Gumbert (Fig. 17). Once one has thought this through properly, one will not be offended by the remains of the letter that still exist today [in 7Q5], but will confidently interpret them as nu.”7

It is a baffling argument. According to this scenario, someone that could hardly write their own name or keep to a straight line would have managed to copy out (at least) two full sentences from the Gospel According to Mark in a literary script complete with serifs and sense spaces, but also with an intention to write the letter nu on the model of an obsolete documentary form (but only sometimes!).

Hunger followed up his defense of Thiede with a pretty shocking statement: “If someone rejects a meaningful decipherment and identification of a text, they should feel obligated to offer an alternative.”8 So, Hunger’s position is effectively that a manifestly incorrect identification is better than having the humility to admit the evidence is insufficient to make a confident identification. This is simply bad scholarship.

Finally, Hunger ended his chapter with an argument that is theological rather than palaeographic: If people disagree that 7Q5 is a copy of Mark, it can only be because “their hearts have been hardened” (Mark 6:52).

Whether or not one agrees with Thiede’s characterization of Hunger as “a classical papyrologist” with “no vested theological interests,” Hunger’s papyrological arguments on display in this chapter are poorly formed and completely unconvincing. Hunger’s argument is internally inconsistent, and neither of the two inconsistent parts of the argument is convincing on its own. Nothing about the script of 7Q5 indicates that it was the product of a βραδέως γράφων; the few extant letters have the appearance of being written by someone comfortable with copying literary Greek. At the same time, the alleged palaeographic parallels that Hunger presents with competent hands are not really relevant to the script of 7Q5.

So, when it comes to the readings of 7Q5, appeals to the authority of Herbert Hunger, just like the appeals Montevecchi, carry no weight.

- See, for example, E.J. Epp and L.W. Hurtado, “Qumran Greek Fragments 7Q3-7Q19” in The Dead Sea Scrolls: Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek Texts with English Translations, vol. 5B (Westminster John Knox, 2024): “The chief problem was O’Callaghan’s need to assume or propose a number of highly unlikely or quite impossible readings, such as ν in line 2, when it is clearly ι-adscript.” ( ↩︎

- Carsten Peter Thiede, The Earliest Gospel Manuscript? The Qumran Papyrus 7Q5 and its Significance for New Testament Studies (Pater Noster Press, 1992), 35. ↩︎

- The booklet was H. Hunger, Die Papyrussammlung der Österreichischen Nationalbibliothek. Katalog der ständigen Ausstellung (Biblos-Schriften 35; Vienna: Österreichische Nationalbibliothek), 1962 (37 pages and 16 plates).

The editions of papyri that I have been able to identify are the following:

H. Hunger, “Ein neues Septuaginta-Fragment in der Österreichischen Nationalbibliothek,” Anzeiger der Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften, philosophisch-historische Klasse 93 (1956) 188-199.

H. Hunger, “Die Logistie – ein liturgisches Amt. (Pap. Graec. Vindob. 19799/19800),” Chronique d’Egypte 32 (1957) 273-283.

H. Hunger, “Zwei unbekannte neutestamentliche Papyrusfragmente der Österreichischen Nationalbibliothek,” Biblos 8 (1959) 7-12 [updated in H. Hunger, “Ergänzungen zu zwei neutestamentlichen Papyrusfragmenten der Österreichischen Nationalbibliothek,” Biblos 19 (1970) 71-75].

H. Hunger, “Zwei Papyri aus dem byzantinischen Ägypten (Pap. Graec. Vindob. 16887 und 4),” Jahrbuch der Österreichischen Byzantinistik 9 (1960) 21-30.

H. Hunger, “Eine frühe byzantinische Dialysis-Urkunde in Wien (Pap. Graec. Vindob. 16),” Jahrbuch der Österreichischen Byzantinistik 10 (1961) 1-8.

H. Hunger and A. Fackelmann, “Grundsteuerliste aus Arsinoe in einem Papyruskodex des 7. Jahrhunderts. Ein neuartiger Restaurierungsversuch an Pap. Graec. Vindob. 39739,” Forschungen und Fortschritte 35 (1961) 23-28.

H. Hunger, “Pseudo-Platonica in einer Ausgabe des 4. Jahrhunderts. Ein neues Fragment in der Papyrussammlung der Österreichischen Nationalbibliothek (G 39846),” Wiener Studien 74 (1961) 40-42

H. Hunger, “Ein Wiener Papyrus zur Ernennung der Priester im römischen Ägypten (Pap. Graec. Vindob. 19793),” Acta Antiqua Academiae Scientarum Hungaricae 10 (1962) 151-156.

H. Hunger Herbert and E. Pöhlmann, “Neue griechische Musikfragmente aus ptolemäischer Zeit in der Papyrussammlung der Österreichischen Nationalbibliothek (G 29.825 a-f),” Wiener Studien 75 (1962) 51-78.

H. Hunger, “Papyrus-Nachlese zu Homer (Unbekannte Fragmente aus der Papyrussammlung der Österreichischen Nationalbibliothek.),” Wiener Studien 76 (1963) pp. 159-162.

↩︎ - H. Hunger, “Zur Datierung des Papyrus Bodmer II (P66),” Anzeiger der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, philosophisch-historische Klasse 97 (1961) 12-23. Although Hunger’s article was cited with some frequency, the dated documentary parallels that Hunger proposed for the script of P.Bodmer 2 were described by Eric G. Turner as “not cogent.” For the assessment and Turner’s alternative analysis of P.Bodmer 2, see E.G. Turner, Greek Manuscripts of the Ancient World (Oxford, 1971), 108. ↩︎

- The chapter was the published version of a paper given at a symposium on 7Q5 held at the Katholische Universität Eichstätt in 1991: B. Mayer (ed.), Christen und Christliches in Qumran? (Regensburg: Pustet, 1992). ↩︎

- On the term and phenomenon, see H.C. Youtie, “βραδέως γράφων: Between Literacy and Illiteracy,” Greek Roman, and Byzantine Studies 12 (1971) 239-261. ↩︎

- “Die “Urform”, auf die das in Zeile 2 vorliegende umstrittene Ny zurückgeht, findet sich auch bei Gumbert (Abb. 17). Wenn man das einmal richtig überlegt hat, wird man auch an den heute noch vorhandenen Resten des Buchstabens keinen Anstoß nehmen, sondern sie getrost als Ny deuten” (Hunger, “7Q5: Markus 6,52-53 – oder?” 37). ↩︎

- “Wer eine sinnvolle Entzifferung eines Textes und dessen Identifizierung ablehnt, sollte sich verpflichtet fühlen, eine Alternative anzubieten” (“7Q5: Markus 6,52-53 – oder?” 39). In point of fact, many alternative identifications have been proposed, though none has proven fully convincing. ↩︎

“A classical papyrologist like Herbert Hunger, with no vested ‘theological’ interest either for or against the proposed New Testament passage, accepted the nu without the slightest hesitation.”

Three points made, and only the first one may be factual. Whenever I am obliged to engage in “footnote surfing” I often encounter shallow – nay, hollow – examples like these. The resulting choice is to evaluate the initial statement and its owner / sender: is it due to incompetence, or malintent?

I always follow up with the author, when possible, and below follows my last exchange. What I refer to as “four pillar story” is Irenaeus’ Against Heresies Book 3 Chapter 11 (https://www.newadvent.org/fathers/0103311.htm) that is literally cited in the book at hand, ON THE ORIGIN OF CHRISTIAN SCRIPTURE page 14:

QUOTE

…it is fitting that she should have four pillars, breathing out immortality on every side, and vivifying men afresh. (Against Heresies 3:11:8)

Because the four authors Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John appear in the exact order as they do in the Four-Gospel volume, Irenaeus is most likely depending on the Canonical Edition.

UNQUOTE

MY EMAIL:

On Fri, Nov 10, 2023, 21:43 <foo@bar.com> wrote:”Because the four authors Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John appear in the exact order as they do in the Four-Gospel volume, Irenaeus is most likely depending on the Canonical Edition.”

I presume you did this from memory, which most certainly is prone to failure

John, Luke, Matthew, Mark – that is the order of the four pillar story, with the two Chrestian gospels (*Ev disguised as Luke) up front. Irenaeus hands out extremely important information on the state of affairs at that point, with Christianity trying to infiltrate the Chrestian movement with their own gospels while still putting the very first gospel ever at the very first position, and *Ev by proxy as second

RESPONSE BY DAVID TROBISCH:

Well, I can’t remember whether I forgot or forgot to remember.

Sorry to be so ignorant, but what do YOU think the letters read as? Rebecca

I think the first editors were right: tau, omega, and iota are certain. alpha is probable (thus the sub-linear dot indicating some uncertainty in their edition).

If someone can just provide good images of the back of the Cave 7 papyri then we will have a means to confirm or reject the view that several of them are either from I Enoch, or more likely in my view, from Deuteronomy.

Matthew Hamilton

Sydney, Australia

I second your request, Matthew Hamilton, for good images of the back sides of Cave 7 papyri, but what–so far–suggests text might be from Deuteronomy?

Hi Stephen,

Not referring to 7Q5 but to 7Q6a, 7Q6b , 7Q7, 7Q9. If they are from Deuteronomy (or for several other 7Q papyri from I Enoch) then it strengthens the argument that 7Q papyri are from the OT and related texts (just like 7Q1 and 7Q2)

See for Deuteronomy:

“A Proposal for a New LXX Text among the Cave 7 Fragments”, by L. Blumell, RQ, no.109 Tome 29 fasc.1 (Juin 2017), p.105-117

“Les fragments de papyrus 7Q6 1-2, 7Q9 et 7Q7 = pap7QLXXDt”, by É. Puech, RQ, no.109 Tome 29 fasc.1 (Juin 2017), p.119-127

Matthew

Pingback: The Roundup – 10.26.25 – The Amateur Exegete