I am fascinated by the Wikipedia entry for 7Q5, which seems to continuously bounce back and forth between being useful and informative to being goofy and borderline incoherent. 7Q5 is a tiny fragment of papyrus found in Cave 7Q at Qumran that contains an unidentified text in Greek. As I noted in an earlier post, it was a mistaken reading of a printed edition (not the manuscript itself) that led the Spanish scholar José O’Callaghan to conclude that fragment contained a portion of the Gospel According to Mark in the 1970s. This created a sensation because it is generally accepted that the manuscripts in the caves at Qumran predate the sack of Qumran in the late 60s CE. O’Callaghan’s error was pointed out immediately, but instead of admitting the slip, he doubled down, and his mistaken identification of 7Q5 has had a persistent afterlife.

The arguments against O’Callaghan’s proposal are compelling.1 Most importantly, O’Callaghan’s reconstruction both depended upon impossible or highly suspect readings of several letters and necessitated that one out of the mere nine undisputed letters on the papyrus must be a scribal error.

After a flurry of articles in the 1970s demonstrating the problems with O’Callaghan’s thesis, it largely (and justifiably) fell out of view, only to be revived in the 1990s by Carsten Peter Thiede (1952-2004).

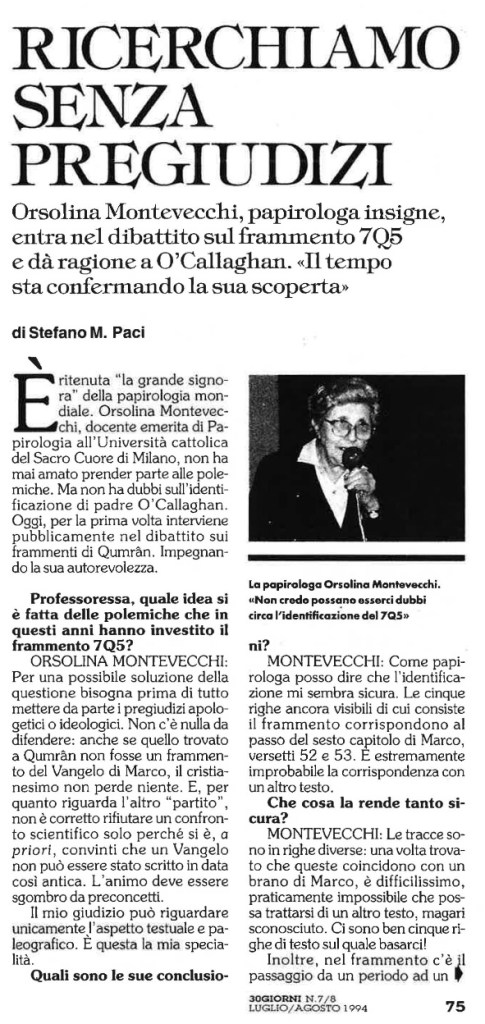

In my earlier post on 7Q5, I pointed out that what was once a reasonably informative article on Wikipedia had become a confused collection of misinformation. The article was then cleaned up but has again become a jumble of decent scholarship and nonsense. One of the recent changes to the entry is a series of appeals to authority, especially that of Orsolina Montevecchi (1911-2009), an Italian papyrologist who endorsed O’Callaghan’s identification of 7Q5 as a fragment of Mark. However, these appeals to authority tend to be by way of hearsay. For instance, many appeals to authority come by way of Thiede. In a book co-authored with the journalist Matthew D’Ancona, Thiede presented Montevecchi’s view as decisive:

“In 1994 the last word on this particular identification seemed to have been uttered by one of the great papyrologists of our time, Orsolina Montevecchi, Honorary President of the International Papyrologists’ Association. She summarized the results of her analysis in a single, unequivocal sentence: ‘I do not think that there can be any doubt about the identification of 7Q5.'”2

This confident assertion made me wonder: What was Montevecchi’s actual reasoning? As far as I have been able to tell, in her massive bibliography, Montevecchi mentions 7Q5 just twice (I would be happy to be corrected if anyone knows of additional references) [[Update 24 May 2025: The count is up to three; see in the comments below]].

The first reference appears in her introductory textbook, La papirologia (1973). The preface to this book is dated May 1972. That is to say, a little more than one month after the first appearance of José O’Callaghan’s first publication on 7Q5 in the first issue of the 1972 volume of Biblica (which carried a print date in March of 1972). That is to say, this statement was composed before any of the rebuttals to O’Callaghan had had been published. At the conclusion of a list of the New Testament papyri that had been published to date, we find a single sentence:

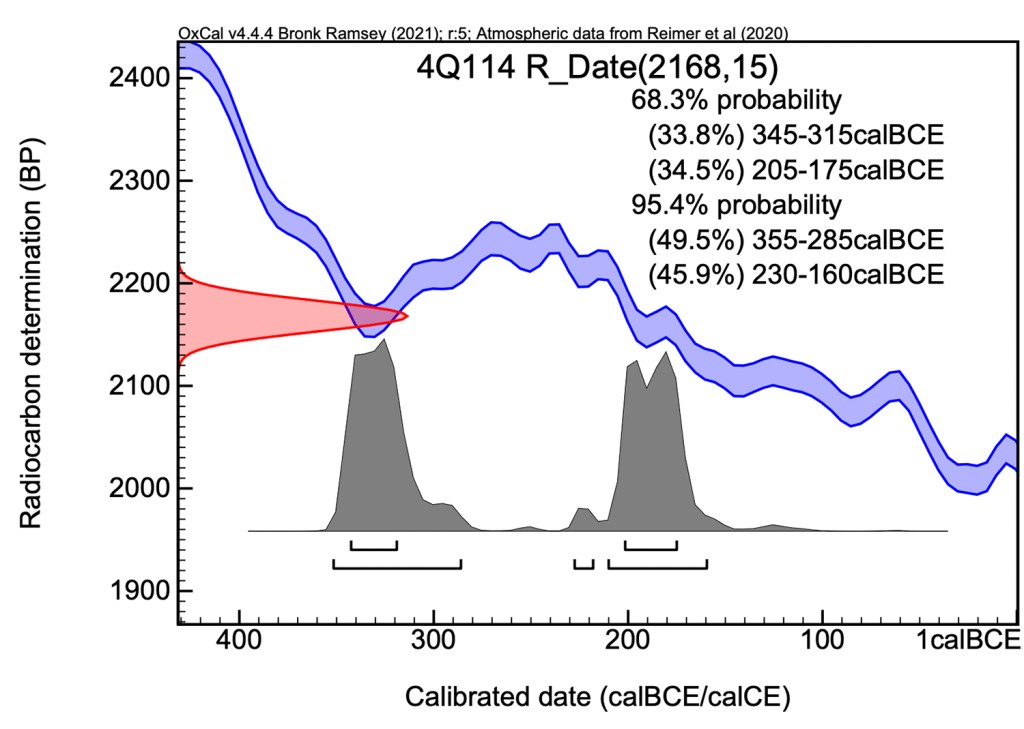

“Furthermore, in the papyrus fragments 7Q5, 7Q6 (frag.1), and 7Q8, palaeographically datable to 50 BCE – 50 CE, have been recognized respectively, Mark 6:52-53 and 4:28 and James 1:23-24 (O’Callagahan, J. in Biblica 53 [1972], 91-100) [“Inoltre nei frammenti papiracei 7Q5, 7Q6, 1, 7Q8, paleograficamente datibili c. 50a-50p, sono stati riconosciuti rispettivamente Mc. 6, 52-53 e 4, 28 Iac. 1, 23-24 (O’Callaghan, J. in «Biblica» 53 1972, pp. 91-100).”]

As far as I know, that is all Montevecchi ever said about this papyrus in an academic publication. The other reference that comes up frequently is an interview conducted for the Catholic periodical 30 Giorni in 1994.

This article, which is the source of Thiede’s quotation endorsing the identification 7Q5, actually has an extended interview with Montevecchi, in which she outlines her reasoning for accepting the identification. It’s fascinating to see what she actually says.

Interviewer: Many excellent palaeographers do not agree with this identification.

Montevecchi: There are some difficulties because three words are missing from the text (epi tēn gēn = “to the land”) compared to the passage in Mark. We read in the gospel text handed down to us: “Having crossed the lake to the land.” But that “to the land” is superfluous. When one crosses a lake, one obviously goes to the other side. In fact, even though these palaeographers seem to ignore it, it’s quite common in the oldest texts of the Bible on papyrus to find the omission of some element not necessary for the understanding of the text. It is as if such words were added later, by way of explanation. Another source of opposition is the fact that there is an exchange of consonants, a tau (t) instead of a delta (d). But this is also a frequent error. Because texts were dictated, the writer transmitted errors of pronunciation. These are the only two objections, which are taken as an excuse to invalidate the identification of this papyrus, since they are the only variations from the text as it was handed down.3

Regardless of how good a papyrologist Montevecchi may have been or how important she may have been to the field, this is simply a very bad argument. Montevecchi neglects even to mention the most compelling counterargument to the identification–the fact that several of O’Callaghan’s readings of letters are wrong, doubtful, or impossible to verify. It is that fact, combined with the need to consider one of only nine undisputed letters as an error, combined with the need to posit the existence of the existence of an otherwise unattested textual variant (διαπερασαντες ηλθον εις γεννησαρετ in Mark 6:53), which makes the identification extremely doubtful if not impossible. Montevecchi was either not fully informed about the scholarly debate around the fragment, or she simply decided to try to defend O’Callaghan’s position by mischaracterizing the opposing arguments and ignoring the most damaging evidence against O’Callaghan’s identification. In the matter of 7Q5, the appeal to Montevecchi’s authority actually adds nothing of substance to the discussion.