In my previous post, I reviewed a recent article by Scott Charlesworth on British Library Pap. 2053, a papyrus from Oxyrhynchus with the ending of Exodus on one side (P.Oxy. 8.1075) and the opening verses of Revelation on its reverse (P.Oxy. 8.1079). In a 2013 article in Novum Testamentum, I had argued that this papyrus was probably a leaf from a codex rather than a portion of a roll, as was usually believed. Charlesworth’s claim that “all indications” point to this piece being a roll and not a codex was not persuasive.

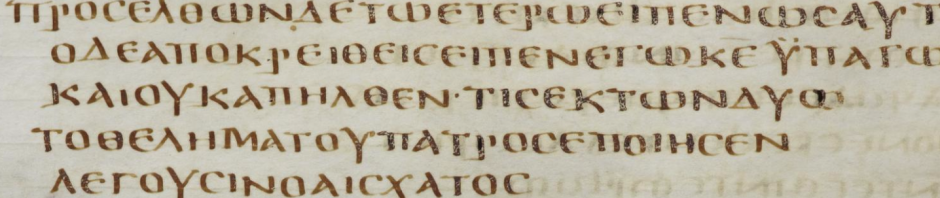

P.Oxy. 8.1075 (→ of British Library Pap. 2053); image source: The British Library

In the current (2019) issue of New Testament Studies, Peter Malik makes a case similar to that of Charlesworth, although Malik’s argumentation is more nuanced. Malik’s full article can be viewed here. Let’s have a look at his case.

Date: Malik first discusses the date of the copying of Revelation. To be clear, Malik does not claim that the date of the papyrus has any bearing on the question of its format, but since he brings up the issue, I offer some observations. Malik prefers a third century date, in agreement with the recent assessment of Pasquale Orsini and Willy Clarysse. It’s no secret that I am suspicious overly fine assignment of dates by palaeography. Parsing between the third and fourth century is tricky. But I’m not going to harp on that point now. What is interesting is that Malik also notes (and tacitly assents to?) Arthur Hunt’s original opinion that the copying of the Exodus side of the fragment “does not seem to be later than the third century.” That is to say, from a palaeographic standpoint, the writing on the two sides of the papyrus is essentially contemporary. This is just what we might expect if the papyrus is a leaf of a codex. It is also compatible with the notion of a reused roll, provided that the reuse happened relatively soon after the initial copying of the front of the roll. In general terms, an earlier date for the papyrus may increase the likelihood that it is a roll rather than a codex, but it is usually claimed that already in the third century Christians showed a preference for the codex format, especially for “scriptural” wiritings. In any event, the issue of the date of the papyrus seems to me to be a neutral point with regard to the question of whether the piece is a codex or a roll (but see below on the question of codex construction).

Contents: Malik accepts my observation that the material on the papyrus is consistent with a codex leaf:

“First of all, Nongbri notes that the format of the original page and column broadly fit with patterns observable in other contemporary papyrus codices. . . [W]hat the extant fragment preserves, on both sides, is a single column of text along with a margin. While, in general, Nongbri’s observation is correct, it does not impress as an argument against the roll format.”

I agree, and I don’t think my article claims that this point should be an argument against the piece being a roll. Rather, I wanted to point out that the pattern of text that we find on the papyrus (in Malik’s words, “on both sides a single column of text along with a margin”) is exactly what we would expect if the piece is a leaf of a codex. Malik’s next sentence is also illuminating for thinking about this issue:

“After all, single-column fragments of what once were more extensive rolls are not uncommon.”

Yes, but the specific point at issue is “fragments of what were once more extensive rolls” that preserve no more or less than a single column of writing on both sides. How common is that? (It’s an honest question–I don’t know the answer.) If our Exodus/Revelation papyrus is indeed a portion of a reused roll, it would seem to be a very happy coincidence indeed that this surviving portion of the roll preserves exactly a single column of text on each side.

Codices with diverse contents: Like Charlesworth, Malik is hesitant to accept a comparison of Pap. 2053 with leaves of codices with diverse contents, especially with the leaf from P.Bodmer 20+9 that I used as a comparandum:

“It is not impossible that our papyrus is an instance of such a codicological arrangement, so that the book of Exodus and the Apocalypse may have been, for whatever reason, copied by different scribes within the same codex. It must be noted, however, that the Bodmer Composite codex would not seem to be the most fitting parallel in this particular case: it is a compilation of a wider array of comparatively shorter texts with a rather complex codicological make-up. In our case, however, we would appear to have two substantial works copied consecutively.”

A couple of observations are in order. In the case of the Bodmer Composite Codex, we are fortunate that the whole thing is preserved, and thus we know with certainty that it includes, for example, only the eleventh Ode of Solomon and not a longer selection from that work. If all that had survived was a single leaf from this part of the codex. we would be unable to know that the codex only included just the single ode. And this is true of fragmentary pieces in general. We usually assume that they contain the whole work of which they are a part, but it helpful to remember that this is, in fact, an assumption (for an interesting case of the problems that this assumption can sometimes cause, see Roger Bagnall’s discussion of papyri containing the Shepherd of Hermas in his Early Christian Books in Egypt). For the sake of argument, let’s go ahead and assume that the Oxyrhynchus papyrus in question was part of a larger whole that contained all of Exodus and all of Revelation. Would this be unusual?

Malik extrapolates that a codex of this layout would require about 117 leaves, and he is hesitant that our papyrus could be a part of such a codex:

“Granting that miscellaneous papyrus codices of this size are not unheard of in the late third/early fourth century, the odd combination of books, coupled with some codicological difficulties that would have to have been involved, renders the miscellaneous codex, in my mind at least, a less attractive hypothesis.”

I don’t regard the “odd” combination of books as an issue (well preserved ancient codices often contain combinations of material that can be surprising to us), and in a footnote Malik mentions a decent comparandum for this hypothetical codex: British Library Ms. Or. 7594, which contains Deuteronomy, Jonah, the Acts of the Apostles and probably had 138 leaves (only 109 survive). What, then, are the “codicological difficulties”? In a footnote, Malik explains:

“In the case of single-quire construction (the most common kind of papyrus codex in this period), one would have to reckon with…”

So, it seems Malik is assuming our papyrus would belong to a single-quire codex because this was “the most common kind of papyrus codex in this period.” If, for the sake of argument, we grant the third century date, we can ask: Was the single-quire codex in fact the most common type of papyrus codex in this period? Again, it’s an honest question. I don’t know the statistics off the top of my head. In fact, I doubt there is much hard evidence, since the pool of pertinent codex samples datable by some relatively objective means will be very, very small (if it exists at all). Given the uncertainty of palaeographic dating and our lack of knowledge about how and when the technology of the multi-quire codex spread in Egypt, I don’t know that I find this objection compelling.

Orientation: With regard to the question of front-to-back orientation, Malik comments that “papyrological experience does seem to confirm that rotating the roll was the more usual,” but because in his estimation “reused rolls beginning the same way up occur fairly regularly, . . .in the end, a reused roll that was not rotated 180° might well appear a little less curious than a kind of composite codex that Nongbri envisages.” Fair enough. We’ll agree to disagree on that.

Finally, Malik also mentions van Minnen’s claim that the apparent struggle of the copyist of Revelation to write against the fibers “definitely” shows that the pieces is a reused roll. I think my earlier post sufficiently demonstrated the weakness of that claim.

I should finish up by saying that I very much agree with Malik’s closing thoughts on the problematic nature of bringing a public/private dichotomy to the analysis of early Christian manuscripts.

Working through these two articles reinforces for me the conviction that we really do need a thorough survey of reused rolls. It would be great to have some statistics, however incomplete they may be, to get a sense of what is “normal” practice (if there is such a thing) in reused rolls, particularly those with literary material on both sides. This question of front-to-back orientation (are the texts copied on the two sides more usually right-side-up or upside-down relative to one another?) is intriguing to me.

In closing, I’ll repeat a point I’ve emphasized elsewhere: When it comes to early Christian manuscripts, we need to avoid pretending to be more certain than the evidence allows (it is Charlesworth’s work, not Malik’s, that really displays this kind of overconfidence). I still think, as I argued in 2013, “there is nothing about the physical characteristics of Pap. 2053 that would definitively oppose its identification as a leaf of a codex.” But that is not to say that it must be a leaf of a codex and not part of a roll. Rather, the only thing that is certain is that the papyrus is ambiguous with regard to format. It could be either, and this needs to be kept in mind when we appeal to this piece. In my recent book, I refer to Pap. 2053 as “codex (?).” In my view, that is the best we can do with the evidence currently available. Those who continue to view the piece as roll would be irresponsible not to add a question mark themselves.

“… from a palaeographic standpoint, the writing on the two sides of the papyrus is essentially contemporary. This is just what we might expect if the papyrus is a leaf of a codex. It is also compatible with the notion of a reused roll, provided that the reuse happened relatively soon after the initial copying of the front of the roll. …”

I don’t know either, but I would think it relatively unlikely for a roll to be reused so soon after its initial use, ie, a waste of time and expense to change the use of a roll so soon.

Well, ‘essentially contemporary’ here means ‘within the span of 0–100 years’, given the necessary limits of palaeographical dating. So while your conjecture (‘I would think it relatively unlikely for a roll to be reused so soon after its initial use, ie, a waste of time and expense to change the use of a roll so soon’) might make good sense—although we’d need some more secure data to substantiate this—in this case it’s not that relevant. It could have been 20 years, it could have been 80 or 5 or 100. Or whatever.

I am undecided whether it is a roll or a codex, and excuse me if I missed something, but concerning the paragraph

“Yes, but the specific point at issue is “fragments of what were once more extensive rolls” that preserve no more or less than a single column of writing on both sides. How common is that? (It’s an honest question–I don’t know the answer.) If our Exodus/Revelation papyrus is indeed a portion of a reused roll, it would seem to be a very happy coincidence indeed that this surviving portion of the roll preserves exactly a single column of text on each side.”

I would comment that if one column from the *middle* of a roll were preserved on the recto, then the chances of a nearly-matching column on the verso would be smaller than the chances of a match if indeed this piece were a roll end. That it holds the end of Exodus and the beginning of Revelation (assuming the top edge, with room for initial Rev. verses, is missing) might suggest (but not prove) the end of a roll. After all, if using a similar margin, one side of the column already aligns as a given (unlike in a mid-roll scenario), so if similar column width was used, the match of columns may not occasion much surprise.

Also, though I may be on thin ice, let me go further: aren’t Exodus and Revelation both scroll-prominent books, and scribes knew that? So, given a choice….

Hi Brent, I wrote a little report of your helpful responses on the ETC blog: https://evangelicaltextualcriticism.blogspot.com/2018/12/brent-nongbri-responds.html