As I compiled stories of discoveries of early Christian manuscripts for my book, God’s Library, one of the recurring tropes I encountered was the claim (usually by European and American scholars and collectors) that native Egyptians burned manuscripts. Such stories circulated about the Beatty Biblical Papyri, the Bodmer Papyri, the Nag Hammadi Codices, Codex Sinaiticus, and the Tura Papyri (for further details and references, see the entry for “burning of manuscripts” in the index of God’s Library).

As I compiled stories of discoveries of early Christian manuscripts for my book, God’s Library, one of the recurring tropes I encountered was the claim (usually by European and American scholars and collectors) that native Egyptians burned manuscripts. Such stories circulated about the Beatty Biblical Papyri, the Bodmer Papyri, the Nag Hammadi Codices, Codex Sinaiticus, and the Tura Papyri (for further details and references, see the entry for “burning of manuscripts” in the index of God’s Library).

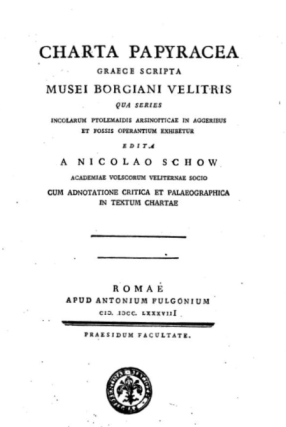

The idea that “the natives burned” manuscripts is a trope that goes back to the very beginning of European encounters with Egyptian papyri. The earliest such report known to me is Nicolao Schow, Charta papyracea graece scripta musei Borgiani Velitris (Rome: A. Fulgonium, 1788), iii–iv: “diripiebant Turcae, earumque fumo (nam odorem fumi aromaticum esse dicunt) sese oblectabant” (the Turks tear them up; they are delighted by the smoke, for they say its smell is aromatic).I was reminded of this recently when reading As I Remember: The Autobiography of Edgar J. Goodspeed (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1953). By way of background, Goodspeed (1871-1962) was a New Testament scholar at the University of Chicago with a keen interest in New Testament manuscripts, perhaps best known for his English translation of the entire New Testament (The New Testament: An American Translation, 1923). He eventually retired to California. Quite early in his career, Goodspeed began to accumulate his own collection of ancient manuscripts. In the late 1890s when, with the help of University of Chicago Egyptologist James H. Breasted (1865-1935), he bought “two large tin cigarette boxes” of papyri from a dealer in Asyut. In the course of describing the many scholars who visited the University of Chicago during his tenure, Goodspeed related the following anecdote involving his papyri:

“In August, 1909, George Milligan, then minister of Caputh, in Scotland, but afterward Regius professor of biblical criticism and Vice-chancellor in the University of Glasgow, visited Chicago and stayed with us. We very much enjoyed showing him Chicago. He was already deeply interested in Greek papyri, and in writing about them. One evening we were speaking of the old story that the first such scrolls found, back in 1778, the Arabs burned to the number of fifty ‘for the aromatic odor they exhaled,’ evidently supposing they were tobacco. I had some tiny scraps of papyrus with no writing on them, and I suggested we experiment with them to see if when burned they possessed any such aromatic qualities. We did so, burning them on a fire shovel and eagerly sniffing the fumes, which smelled just like burnt brown paper. I have tried this experiment since on dried papyrus from my California garden, with the same result. No, the Arabs who burned those fifty first Greek scrolls were disappointed, that is all.” (As I Remember, pp. 124-125)

“In August, 1909, George Milligan, then minister of Caputh, in Scotland, but afterward Regius professor of biblical criticism and Vice-chancellor in the University of Glasgow, visited Chicago and stayed with us. We very much enjoyed showing him Chicago. He was already deeply interested in Greek papyri, and in writing about them. One evening we were speaking of the old story that the first such scrolls found, back in 1778, the Arabs burned to the number of fifty ‘for the aromatic odor they exhaled,’ evidently supposing they were tobacco. I had some tiny scraps of papyrus with no writing on them, and I suggested we experiment with them to see if when burned they possessed any such aromatic qualities. We did so, burning them on a fire shovel and eagerly sniffing the fumes, which smelled just like burnt brown paper. I have tried this experiment since on dried papyrus from my California garden, with the same result. No, the Arabs who burned those fifty first Greek scrolls were disappointed, that is all.” (As I Remember, pp. 124-125)

Goodspeed’s conclusion that the Arabs were disappointed is of course possible, but it seems to me equally possible that most of, if not all of, these stories are nothing more than that–stories. The line that “the natives burn the ancient manuscripts” surely serves American and European scholars and collectors in justifying their acquisition of ancient manuscripts (“rescuing” them, to use the standard terminology). That’s not to say that such burnings never happened. The case of the Nag Hammadi codices is interesting, in that the Egyptian finder himself claims that some of the codices were burned.

From my own experiments burning small scraps of modern papyrus leftover from some of my bookbinding projects, I can say papyrus burns up extremely quickly. It would not be much good for fuel, although I guess it could be useful for kindling to get a fire started.

Reblogged this on Talmidimblogging.

On “I can say that papyrus burns up extremely quickly,” here’s what E. S. Stevens, Lady Drower, wrote in 1912 (My Sudan Year, p. 194) on burning even in situ:

“The next morning found us moving steadily through the papyrus country. But, soon after breakfast, the colour of the swamp changed abruptly. A devastating grass fire had passed over it, blackened fields of it swayed in the wind, the graceful glory of plumed head and straight green stem had been turned into a mere wisp of fibre at the top of a charred straw. From the funereal waste of burnt papyrus, we came to the burning papyrus. The tall rushes were flaming close to the water’s edge, indeed, we were in some concern at the sparks, though we kept to the middle of the channel. It was a wonderful sight, flames and smoke leapt sky-high, and a roaring, crackling sound was emitted as the beautiful green papyrus was licked up. the fire travelled at right angles to the river. We were glad to leave it behind.”

It should always concern us when it is the non WASP always doing the “savage” act. Thanks for this bit of history!

Pingback: Livius Nieuwsbrief | Maart 2019 – Mainzer Beobachter