This is the third in a series of questions relating to the source of the first seven Dead Sea Scrolls to appear on the market in 1947. The first post dealt with the Genesis Apocryphon, and the second with the Thanksgiving Scroll.

Now I move on to some questions about the cave itself. The cave we call “Cave 1” is generally regarded as the find spot of the first seven scrolls that showed up on the market in 1947, which we have been discussing:

Rule of the Community (1QS)

The Habakkuk Pesher (1QpHab)

The Great Isaiah Scroll (1QIsaa)

The Thanksgiving Hymns (1QHa)

The War Scroll (1QM)

A second copy of Isaiah (1QIsab)

The Genesis Apocryphon (1QapGen)

What do we know about this cave? It is thought to have been “visited” on several occasions before being excavated by professional archaeologists. Here is an extract from John C. Trever’s outline of events relating to the discovery of the scrolls, The Untold Story of Qumran (1965), pp. 173-180:

| 1946, November – December (or possibly January – February 1947) | Ta’amireh Bedouins (Muhammed edh-Dhib, Jum’a Muhammed and Khalil Musa) happen upon Cave I near Khirbet Qumran and discover three manuscripts in a covered jar. They remove these and two complete jars. |

| 1947, May or June | Ta’amireh Bedouins take [George] Isha’ya to cave. Later [when? — BN] Isha’ya and Khalil Musa secure four more scrolls, three of which they sell to Faidi Salahi, another Bethlehem antiquities dealer. The fourth scroll is kept by Kando. |

| 1947, August | Isha’ya takes Father Yusif from Syrian Monastery to visit Cave I. |

| 1948, August(?) | Apparently during second truce [during the Arab-Jewish conflict] Isha’ya visits cave again and secures Daniel and Prayer Scroll fragments and a few others, which are turned over to St. Mark’s. |

| 1948, November | Isha’ya, Kando, and others “excavate” cave and secure many more fragments |

| 1949, January | Dr. O.R. Sellers and Yusif Saad seek to locate cave. Isha’ya demands payment, and negotiations cease. |

| 1949, January 24 | Captain Philippe Lippens elicits aid from Arab Legion to relocate cave. |

| 1949, January 28 | Captain Akkash el-Zebn rediscovers cave near Khirbet Qumran |

| 1949, February 15 – March 5 | Cave I (1Q) excavated. Fragments of about seventy scrolls recovered, and pieces of fifty pottery jars and covers. |

So, the cave that was excavated by de Vaux and G. L. Harding in February-March 1949 was said to have been “rediscovered” after several visits by looters (and apparently “rediscovered” without the aid of any of the previous visitors). Here is how Harding summed up matters in the first volume of DJD:

“Then a Belgian observer on the United Nations staff, Captain Lippens, who had become interested in the story of the find, raised the question with Major-General Lash of the Arab Legion. Lash offered, …to send a small contingent of men to the area where the cave was believed to be located in order to try to rediscover it. This was done at the end of January 1949, and the cave was actually found by Captain Akkash el Zebn after only two or three days’ search. The discovery was duly reported back to headquarters, and I went down to examine the place. At first I was sceptical whether it could really be the right cave, but the presence of many potsherds and fragments of linen showed that it had at least been occupied and must be investigated. Accordingly on 15 February the Jordan Department of Antiquities in collaboration with the École Biblique et Archéologique Française and the Palestine Archaeological Museum started work there and continued until 5 March 1949.”

Harding was satisfied that they were in the right place by the evidence of occupation. His supposition seemed to be confirmed by the discovery of two small bits of the War Scroll (1Q33) among the fragments in the cave. And yet, the cave was very clearly a contaminated context, as Millar Burrows vividly describes in his account of the excavation in The Dead Sea Scrolls (1955, p. 34):

“Much recent evidence of depredation was found also. Mixed up with the ancient debris were found exasperating remains of the disastrous efforts of the treasure-hunters the previous winter. There were bits of modern cloth, scraps of newspapers, cigarette stubs, and even a cigarette roller bearing the name of one of the illegal excavators, which Mr. Harding returned to its owner.”

I truly love that detail about the returned the cigarette roller. But I am less happy from an archaeological standpoint. The fact that the site was so very contaminated decreases the value of 1Q33 as a connection to the find spot of the War Scroll. Harding’s quotation above certainly makes it sound like the excavators were looking for a single, isolated cave that had housed manuscripts, and they were happy when they found one fitting that description. But as we can tell with the benefit of hindsight, there were actually many caves in the region that held manuscripts (and jars and textiles, etc.). So, what was the potential for other depositions in the immediate vicinity of “Cave 1”?

Looking at a typical map of the Qumran caves, the obvious answer would be “Cave 2”:

Cave 1 and Cave 2 really are quite near one another:

So, now comes my first question. When we read about Cave 2 in the traditional story of the scrolls, it is described as not being “discovered” until February of 1952–e.g. in Trever’s timeline: “1952, February: Ta’amireh Bedouins discover Qumran Cave II (2Q) close by 1Q.”

First question: February 1952 is when archaeologists first learned of Cave 2, but is there any actual evidence for the date when looters found it? Might it have been before February 1952?

When archaeologists did arrive at Cave 2, it was thoroughly picked over. In the words of one of the excavators, “signs of illicit digging were very much in evidence” (William L. Reed, “The Qumrân Caves Expedition of March, 1952,” BASOR 135 [Oct. 1954]). In his discussion of the excavation, de Vaux put matters more starkly: “The cave had been entirely emptied” by clandestine diggers (DJD 3, p. 9). Elsewhere (Revue Biblique 60, 1953, p. 553), de Vaux mentions two small manuscripts found in the spoils left behind by the looters.

Second question: Is it right to say that only two of the texts that we call “2Q” can actually be archaeologically connected to the cave we call “Cave 2”? And what are these two?

It seems at least possible that “Cave 2” materials could have been confused with “Cave 1” materials at some stage on their travels through the antiquities market. And to judge from the results of the survey of caves undertaken in 1952, there were at least a few other places in the neighborhood of Cave 1 that could have been sources for “Cave 1” materials. There are several other areas in the vicinity of Cave 1 that de Vaux identified as having been “utilized by the community at Qumran” (Archaeology and the Dead Sea Scrolls). These sites are highlighted in red in the map below.

In DJD 3, de Vaux noted the types of finds in these areas, which include “Qumran” style ceramics. So it appears again that Cave 1 is not the only possible source of some of the well preserved scrolls generally associated with that cave. And there is some further confusion in the early stories.

It is well known that Muhammad ed-Dhib changed his story about the date of the discovery. After relating to Harding and others in 1949 that he had found the first scrolls in 1947, in a later interview (conducted in 1956) Muhammad ed-Dhib claimed he found the scrolls in 1945. Once again Trever sifted the relevant evidence in an article and confirmed the date of discovery as spring 1947.

It seems to be less frequently noted that in the 1956 interview Muhammad ed-Dhib also identified a different place of discovery. As Trever pointed out in the article on multiple occasions: “His description of the entrance to the cave is clearly not that of Qumrân Cave I…Again he is not describing Cave I.” Trever was referring to the fact that Muhammad ed-Dhib’s account did not at all match the “Cave 1” excavated by archaeologists in February and March of 1949, with its distinctive rock formations and openings. Could Muhammad ed-Dhib have misremembered? Trever mentions a conversation he had with de Vaux:

“On May 15, 1958 I discussed the matter with Father R. de Vaux at the École Biblique in Jerusalem, and he told of sitting with adh-Dhib on a large rock within a few feet of the entrance to Cave I and listening to his account of the discovery…”

Sidenote: I wonder if this was the occasion of this photograph of Muhammad ed-Dhib at “Cave 1”:

What are we to make of the messy state of the archaeological evidence and these conflicting stories? In response to the suggestion by Weston Fields that some of the scrolls normally associated with Cave 1 might have been found elsewhere, the authors of a recent thorough and informative treatment of the assemblage from Cave 1 (Joan E. Taylor, Dennis Mizzi, and Marcello Fidanzio) dismissed the idea in a footnote:

“While Fields (2009) has done an excellent job in documenting the evidence, his final conclusions that there may have been scrolls from a different cave that has been confused with Cave 1Q seems unnecessary to us, and creates complexity as a result of affording weight to less reliable anecdotes.”

Unreliable anecdotes are one thing. But the seemingly widespread archaeological contamination at the relevant sites is not so easily brushed aside. When it comes to the first seven scrolls, we are dealing with looted materials, and as a result, unreliable anecdotes are all we have. That and a couple scraps of the War Scroll that were found in a thoroughly disturbed site in close proximity to several other sites that were occupied at the same time, potentially by the same groups of people.

So, third and final question (for today): On a scale of 1 to 10, how confident should we be that all seven of the scrolls on the market in 1947 came from the cave that we now call “Cave 1”?

Before addressing your questions, we need to have clarity about the extent and timeline of the “Cave 1” materials. There clearly is a discrepancy between Trever’s outline and the DJD 1 statements. DJD 1 states explicitly that apart from fragments, and (in the case of 1QS) columns, that had broken off the large scrolls (1QS, 1Q8, and 1Q20) and were kept by Kando, 1Q5 frag. 13, and the few fragments from the last illegal excavations, published in DJD 1 as appendices, all other fragments had been found by the archaeologists. This does not match with “Isha’ya, Kando, and others “excavate” cave and secure many more fragments”. Which “many more fragments”? Certainly not those published in DJD 1. There is, except for the few fragments mentioned above, no report or evidence of Ta‘amireh excavation of other fragments, or of Cave 1 fragments traveling through the Antiquities market. Or, for that matter, of any Cave 1 materials on the market after the 1947/48 selling the materials to Mar Athanasius and Prof. Sukenik, and the (1949 or 1950?) acquisition of the broken off sections of 1QS, 1Q8 and 1Q20 by the Palestine Archaeological Museum.

Thanks again, Brent. It seems to me that we are inescapably dealing with probabilities here, not verifiable yes or no answers. Of course, it is *possible* that not all of what we call the Cave 1 materials are actually from Cave 1, but on balance of all the evidence I find it still to be the most plausible explanation. You offer a good reminder, however, that we need to maintain some circumspection when we write and speak about these scrolls.

The question whether all seven “Cave 1” scrolls actually derived from only one “Cave 1” is legit, given the dissenting reports about the 1947 finds, and I am not entirely confident that they all came from the same cave. The question whether some of the “Cave 1” scrolls might have been found in what we now know as Cave 2 is more problematic. Perhaps the most plausible hypothesis would be to assume (1) that some of the “Cave 1” scrolls had actually been found in Cave 2 at the latest in 1947; (2) that the Ta‘amireh realized from the archaeological excavation of 1949, and the Museum’s late 1951 acquisition of the fragmentary finds of late 1951 (Murabba‘at), that not only scrolls, but also fragments were valuable; (3) that they returned to Cave 2 which they already knew, did a thorough cleaning of the cave—and salvaged all but two tiny fragments which they left in the rubble—rumours of which reached the archaeologists, as reported, in February 1952. De Vaux reports both in RB (see post above) and in DJD 3 (p. 3) on two small inscribed fragments found in the rubble, but there is no published evidence which these two were. The pottery remains found outside Cave 2 attests to the cylindrical jars commonly called scroll jars. This scenario does not require the problematic assumption that what we now know as the Cave 2 fragments were already removed from the Cave much earlier than 1952.

As for the suggestion that only two manuscripts could be archaeologically connected to Cave 2: Given that we do not know which two tiny fragments were found, and if they could actually be associated with any specific fragment manuscript among those excavated by the Ta‘amireh, and given the situation in 1952 and as long as there is no plausible alternative, any suggestion that the published Cave 2 materials are not from the cave we now know as Cave 2 is overly skeptical and also unnecessary for the Cave 2 origin of some Cave 1 scrolls.

As some here know, a small help: “Occasionally the letters G, for government purchase, or E, for excavated fragments, were used to designate the origins of fragment collections. These letters were used to mark photographs, and in some cases G was stamped on the back of fragments.”

Stephen A. Reed, “Survey of the Dead Sea Scroll Fragments and Photographs at the Rockefeller Museum,” Biblical Archaeologist (March 1991) 48.

Two different things are indicated in the quote from Stephen Reed.

The first is that the first two series of photographs of the Cave 4 materials, namely those acquired by the Jordanian Government in 1952 and those which were excavated by Harding, de Vaux, and Milik, were referred to as the G resp. the E-series (see Strugnell in Companion Volume to the Dead Sea Scrolls Microfiche Edition, p. 131).

The second is that some (generally larger) Cave 4 fragments were stamped with a letter on the verso indicating the institution that contributed to the purchase of a specific lot of fragments (see Companion Volume, p. 17). The publicly available photographs rarely show uninscribed verso images, but see, e.g., https://www.deadseascrolls.org.il/explore-the-archive/image/B-283867 which shows three stamped “S”s on the verso of the large 4Q417 fragment, or https://www.deadseascrolls.org.il/explore-the-archive/image/B-370751 with stamped “V”s).

However, this is only a small help for a part of the Cave 4 materials.

Pingback: Biblical Studies Carnival 170 (April 2020) | PeterGoeman.com

Prof. Claus-Hunno Hunzinger stamped the fragments, which had been bought from Kando with the money from Germany – it was brought by Prof. Karl Georg Kuhn in the summer of 1955 from Heidelberg – with an “H” on the backside of the fragments. The lot from Cave 4 was bought for 40.000 DM, which Kuhn brought from Germany. I have nice pictures of Joseph Saad, Claus-Hunno Hunzinger and Karl Georg Kuhn in the PAM sitting on a desk and cheking and stamping the “Heidelberg”-fragments, as Prof. Hunzinger told me with an “H”. But I have never seen any backside of a fragment with an “H”. If anybody “discover” such a fragment in the Leon Levy Digital Library it would be nice to get a notice. My e-mail: Schick.Sylt@gmx.de

This is getting more-and-more off topic, and utterly eccentric (apologies to Brent). Except for opistographs, of only few fragments photographs of the backside of the fragments have been made accessible on the Leon Levy Digital Library, often because traces are visible on the backside, or in the case of large fragments. I have gone through most of them (google search: “verso 4Q site:.deadseascrolls.org.il”) and have only found examples with the stamps S, V (a few) and G (more), though some G stamps might be mistaken for E or Q stamps. Two interesting cases are https://www.deadseascrolls.org.il/explore-the-archive/image/B-370765 (three G’s) and https://www.deadseascrolls.org.il/explore-the-archive/image/B-370877, which has a join of two fragments, one stamped with S, the other with G. Note by the way that there are some errors with regard to “verso” and “recto” in the Leon Levy Digital Library, so I may have missed some with this search.

Thanks a lot for the answer. I was only interested in this question, cause of the pictures we have in the archive from this “stamping” and I thought you know more when we. Thanks again for your answer and the links. But you are totally right! It has nothing to do with the topic, if Cave 1 is really Cave 1. Nobody can answer! It is a nice academic – but sorry to say – fruitless question, cause all the eyewittnesses are dead. And what makes the difference, if they come from 1Q or 2Q? We know them and this is the importance.

Pingback: Qumran Cave 1 Questions, Part 4: Sukenik’s Isaiah Scroll | Variant Readings

This may have been addressed, and I don’t have access to all the relevant publications at the moment, but Harding wrote about his cave excavation in PEQ (1949) p. 113, “A number of the parchment fragments can be identified with some of the eight scrolls already made public, in particular the Habakkuk commentary, the books of Hymns, and the War of the Children of Light.”

You have address the latter two. Are we to assume now that what Harding (provisionally) called the Habakkuk commentary fragment(s) turned out to be what is now known as 1Q bits of pesher of another book or pesharim of other books?

Yes, I don’t think I’ve mentioned this passage on the blog. Because there is no part of the Habakkuk pesher in DJD 1, I assumed that this identification was rejected early on.

The above scholarly contributions question the provenance of the “1Q” finds, and there looms the question: Was “Cave 1” a ruse, sprinkled with scroll fragments and pottery pieces, meant to draw attention away from the true location of the scrolls?

This was clearly Harding’s first impression, who also knew that by accepting it he kept those seven well preserved scrolls and the newly offered fragments within the authority of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan.

Supposing that it was a ruse brings the next question to the fore: are there unidentified (or misidentified) fragments of the same manuscript categorized under more than one cave?

I have never heard if this approach has been applied to the archive.

As an answer to Ralph’s “next question”: this is (up to now) not the case with any of the Cave 1 materials. Well known are the few cases where fragments of apparently the same manuscript were initially assigned to different find-sites (one such case of Qumran Cave 4 and Nahal Hever, and several more of different non-Qumran sites/caves) . Among the Qumran Caves, there is a limited mingling of Cave 4 and Cave 6 fragments (cf. forthcoming article in DSD).

Thank you, Prof. Tigchelaar, for your kind response. I use the two volume Student Edition of you and Martiinez religiously for this subject.

Harding was careful to publish in DJD 1 all the scraps he had obtained, and I think there still may be use to make of them when compared with cave 4 finds. The scrolls suffered terrible mishandling in those early days. We have on film William H. Brownlee fumbling with the Great Isaiah Scroll, so one can easily imagine far worse happening before they got into professional hands. Harding had obtained from Kando, among many valuable fragments, “a solid black mass of what was once a scroll.” Kando had been so nervous about having the illegally excavated scrolls in his home that he decided to bury part of them in his garden, “and when later he went to retrieve them he found only several lumps of sticky glue.”; Allegro, The Dead Sea Scrolls, page 19, Penguin, 1956. Simple math tells us that Harding received one of those “lumps”.

The whole of this blog (thank you Brent) tells us that we should assume that every possible mishandling and shenanigan was perpetrated on the scrolls, from the time two children tossed a rock in a hole and heard it clatter in pottery shards, to when Israeli soldiers pried up the floorboards of Kando’s home to find the Temple Scroll.

Cave 11 might also be “so called”, the same as Cave 1. Thank you all again.

Only short notice … You write “We have on film William H. Brownlee fumbling with the Great Isaiah Scroll” just would like to add the scroll is not 1QJesA but 1QS.

Thank you for that correction.

I saw the film once at an exhibition in San Diego, CA, but no comment was made about which scroll it was (BTW, Lawrence Schiffman spoke later that night giving a general introduction to the scrolls). Those of you who have Scrolls From Qumran Cave 1, Jerusalem, 1972, from photographs by John C. Trever, will find on pages 26, 27, that the black & white photo on the left has a piece, at lines 13, 14, 15, that is missing in the facing color photo on the right; the corresponding photo of The Dead Sea Scrolls of St, Mark’s Monastery, New Haven, 1950, Plate VI, is also missing that piece (the digital DDSs has that piece: http://dss.collections.imj.org.il/isaiah ).

Trever makes no remark about this in his introductory note to the 1972 edition, though he does remark on a floating aleph that appears a couple of times in his photo’s, appearing as it slid along in the process of being photographed, which he identified as belonging to line 3 of column 52, thought I don’t know of it having been restored there.

Though a little off topic, it attest to the frigidity of the MSS.

Combined with Harding’s debacle of offering to pay per square centimeter, and the fact that scholars were hustling through the streets while bombs were going off, it would be wise to suspect any unplaced flake or fragment as having originally belonged to the cave 4 cache (which, for me, if it hasn’t been detected yet, would include all 1Q and 11Q materials.

Sorry about the Freudian slip – I meant the “fragility” of the scrolls. Ralph

Here is one last clarification, to explain my remark about the damage to 1QIsaiah-a.

The lacuna at the bottom of columns 5 and 6 shows a triangle shaped piece on the left that was found when John C. Trever was making his several photo sessions with the scroll, as he states in his volume issued for the Shrine Of The Book in 1972, But the right side shows the loss of letters from column 5 – on line 24 the vav and part of the daleth are gone, and on line 26 the aleph and mem. Indeed, as many letters were lost as were found. Ralph

The article of Eibert Tigchelaar that he mentioned in comments here is (or will be) published as “Two Damascus Document Fragments and Mistaken Identities: The Mingling of Some Qumran Cave 4 and Cave 6 Fragments,” Dead Sea Discoveries 28.1 (2021) 64-74.

Ralph Cox, in your comments here you asked “Was ‘Cave One’ a ruse, sprinkled with scroll fragments and pottery pieces, meant to draw away attention from the true location of the scrolls?” Though it’s likely that some preferred to keep the location of the scroll cave(s) secret, the deposition of items in the “official” Cave One do not strike me as an amateur “sprinkled” decoy. Do you have any reason to support that speculation?

(I have a vague but uncertain recollection of a Cave 11 jar being called a Cave 1 jar, but I haven’t located that claim, if it exists.)

An Advance Article at Dead Sea Discoveries online is:

Getting a Handle on 1QIsaiahb:

A New Proposal for the So-Called Handle Sheet of 1QHodayota

Author: Michael B. Johnson, Pages:1–26

Online Publication Date: 20 Jul 2021

Abstract:

This article examines Hartmut Stegemann’s preliminary proposal that the remains of the beginning handle sheet of 1QHa have survived and provide useful data for reconstructing the scroll. According to Stegemann, this handle sheet supplies critical material evidence that three columns existed before1QHa4, the first substantially extant column in the manuscript. The handle sheet was recovered from one of three scrolls,1QM,1QIsab, and 1QHa. Each of these possibilities is considered, and a new proposal that the handle sheet belongs to the end of 1QIsab is advanced. The article offers a tentative reconstruction of the handle sheet as part of 1QIsab to demonstrate its material continuity with col.28 of 1QIsab.

***

If this proposal is correct, it remains a reassignment within the Sukenik Cave One lot.

Pingback: New Article on the Dead Sea Scrolls said to come from Cave 1Q | Variant Readings

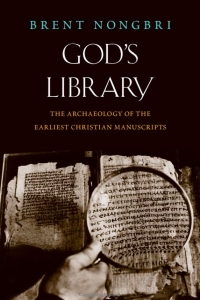

The recent publication of Brent Nongbri’s book about the provenance of the DSSs has re-enlivened this discussion, and in the first of the two posts above Stephan asks (a year ago – my apology) If I and had any other reason for believing Cave 1 was a ruse, as was, as we’ve see above, Harding’s first impression stated in DJD vol.1 (please note there also that most of what Harding publishes in that volume were from “the purchased Lot”, of fragments bought from Kandu, and that Harding’s first visit found only a few valuable fragments in the so-called “dump” of the Bedouins, including mss in Phonetician script, and a lump the was once a scroll. Chapter One of John Allegro’s The Dead Sea Scrolls, 1956, which reads like a good thriller at times, gives many details on the efforts of the authorities to find “the cave” and he points out that the illegal excavators had great fears of being apprehended for their crime, including causing Kandu to bury some scrolls in his flower bed to hide them, and coming back later to find only gluey lumps. I think cave 11 was also a ruse, done in the exact same way, including tossing in another of those gluey lumps – see Revue de Qumran, Jan 1961, “The Scroll of Ezekiel from the Eleventh Qumran Cave” by William H. Brownlee. All of the “Cave 11” scrolls had to be scientifically opened, and not knowing the value of them would have made it better that they be stashed and to wait. There would also have been the question of how to bring them out without it being obvious that they had been stashed, but the fact that Kandu was able to confess having hid (and ruined) some scrolls meant that the authorities were lightening up to encourage the appearance of more finds.

I sometimes believe that the fiction of “Cave One”, and likewise Cave Eleven, is a case where scholarship dare not overturn the apple cart that brings these finds to the public forum.