In the wake of the controversy over the “Newest Sappho” papyrus in the last few years , I’ve read more about the Greek poetess Sappho than I ever thought I would. In doing so, I realized that I have a pretty firm mental image of Sappho, and it’s the marble bust in the Capitoline Museum in Rome.

But of course, this is not a portrait of Sappho. In his catalog of the sculptures in the Palazzo dei Conservatori (1926), H. Stuart Jones unenthusiastically described it as follows:

“Dull Roman work from an original of the early fifth century B.C. sometimes combined with the bearded Dionysus and therefore perhaps Ariadne” (p. 60).

Jones goes on to note that the inscription below the head and the base on which the herm sits are modern.

So, when did this anonymous head become Sappho? Around 1564. Maybe.

The inscription below the head (ΣΑΠΦΩ | ΕΡΕΣΙΑ), Sappho Eresia, has been published multiple times. It was published in 1844 and apparently regarded as an ancient inscription (CIG 6106). It was published again in 1890, but this time it was taken to be a clearly modern inscription (IG XIV 253*). It was described as suspect already in 1845 (“eine weibliche Herme mit Namen Sappho in einer sehr verdächtigen griechischen Inschrift,”) by Platner and Urlichs, Beschreibung Roms, p. 237. The most informative publication is Huelsen 1901, which notes that the inscription shows evidence of erasure of letters under the letters ΣΑΠ. And indeed, this can be seen quite clearly:

But none of these publications offer a guess at when the inscription was added.

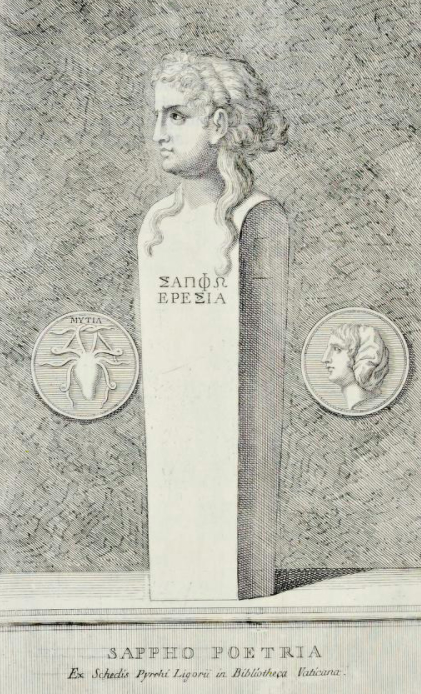

Jones notes that a drawing of the herm was published by by Jacob Gronow (1645-1716) in his Thesaurus Græcarum antiquitatum (1698):

The caption names the source of the drawing as Pirro Ligorio, but the more proximate source is clearly Giovanni Pietro Bellori’s (1613-1696) illustration in Veterum Illustrium Philosophorum Poetarum Rhetorum et Oratorum Imagines (1685):

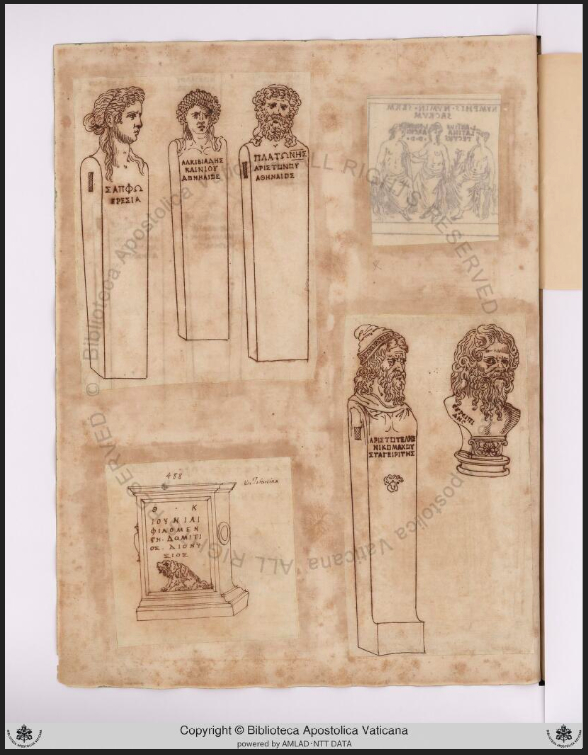

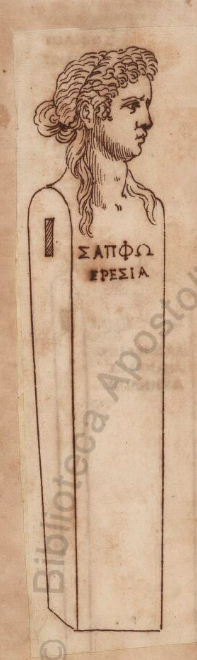

The ultimate source for these images is indeed a manuscript at the Vatican Library, BAV Vat Lat 3439, an album of drawings on sheets that have been repaired and rebound. The drawings were prepared at some point in the 16th century (probably before 1570) and are based on drawings by Pirro Ligorio (1513-1583).

Here is a closer look at the Sappho herm in the Vatican codex:

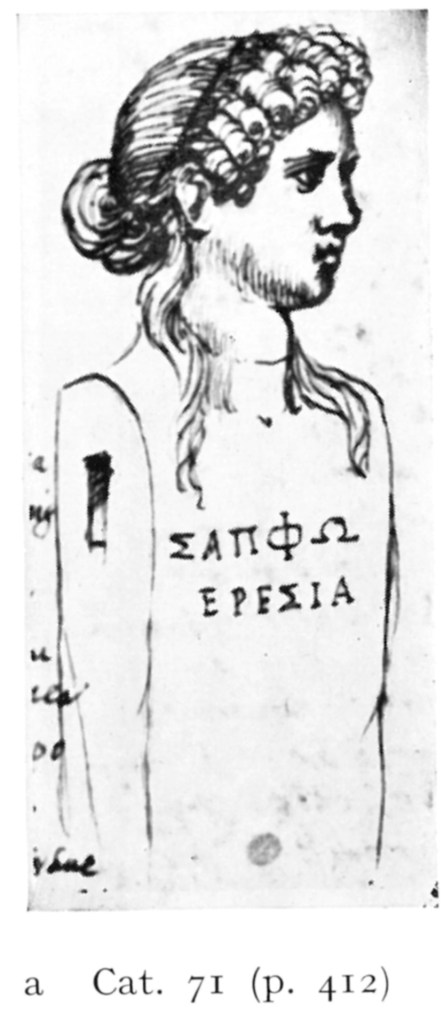

The images in the Vatican manuscript are isolated and without context. The source for these deptictions is generally agreed to be a drawing in one of Ligorio’s manuscripts in the National Library at Naples, Codex XIII.B.7, p. 412. Here is the relevant image of the Sappho:

The drawing is accompanied by a short note. Mandowsky and Mitchell point out that “the drawing and commentary are late insertions into the manuscript” (probably between 1564 and 1570), but it nevertheless seems that Ligorio’s drawing in this manuscript is the earliest record of this sculpture with this inscription. Unfortunately, the note does not provide much help with the history of the artifact itself:

“Sappho Eresia è quella poetessa che scrisse gli Enigmi jambi, et epigrammi et oltre opere, fu contemporanea all’ altra Sappho Mytilenea, viveano ambedue sotto il regno di Tarquinio Prisco in Roma. La Sappho Mytilenea trovò la poesia lyrica [ms.: illyrica], et si precipitò in mare per amore di phaone, furono ambedue dell’ isola di lesbo l’una di Ereso città, l’altra di Mytilene. La Eresia hebbe il borbozzo ò vero mento grossotto.”

So, Ligorio was under the impression that there were two women from Lesbos named Sappho. One (Sappho of Eresos) was a writer of enigmas and epigrams and the other (Sappho of Mytilene) was the lyric poet. Here, then, we get no details about the sculpture itself. For that, it seems we have to look to one of Ligorio’s manuscripts in Turin (Cod. a.II.10.J.23, p. 76). In the course of describing a herm of “Philemon,” Ligorio writes that it

“fu portato in Roma nella villa di papa Julio terzo, et dindi è stata tolto come molti altri ritratti, et posto nel palazzo Vaticano dà papa Pio quarto, et parte egli ne donò et parte ne dedicò nell’ hemicyclo dell’ atrio di Belvedere, dove erano queste effigie di Platone, Isocrate, di Aristide Smyrneo, di Diogene, di Socrate, di Ierone, de Alcibiade, due testa della celeste Vergine, due di Ariadne, l’effigie di Sappho Eresia, et una testa di Serapide; delle quali nella sedia vacante alcune ne furono tolte, altre portate in Capitolio, et quel ritratto che fù più raro fù di Minicio Cippo tolto dalla villa di Horatio.”

So from this note, it would appear that “l’effigie di Sappho Eresia” was among those pieces that Ligorio sourced to decorate the Cortile del Belvedere at the Vatican (1564-1565) when he was papal architect under Popes Paul IV and Pius IV. These sculptures decorated the area only briefly, before they were given to the people of Rome (that is, sent to the Capitoline and other locations) in 1566 by Pope Pius V, who was less of a fan of pagan statuary.

I assume that this quotation is also the source of the association sometimes made between the Capitoline Sappho and the Villa Giulia, but I’ve been unable to find any other connection between this piece and the Villa (I would be grateful to learn if anyone does know other sources that make that attribution explicit). But the sculptures that decorated the Cortile were acquired from all over Rome and the surrounding regions. How can we really know if this piece came from the Villa Giulia?

Mandowsky and Mitchell have an alternative theory. They point out the similarity of a number of the pieces that decorated the Cortile del Belvedere. Herms of Socrates and Alcibiades that stood with the Sappho also consist of ancient heads on modern shoulders. In all three cases, Mandowsky and Mitchell suggest that “the concoction” is probably the work of Ligorio himself.

In addition, the three herms, which have all ended up in the Capitoline Museum, have inscriptions bearing very similar lettering:

Mandowsky and Mitchell reach a similar conclusion regarding these inscriptions: “All three of these inscriptions seem to have been cut by the same hand–very likely Ligorio’s own” (p. 95).

This all seems plausible, but it’s not the only possible story of this Sappho. According to some scholars, Ligorio’s Sappho is not the one in the Capitoline. Gisela Richter (The Portraits of the Greeks, 1965, p. 70) described Ligorio’s Sappho as follows:

“A herm inscribed Σαπφω Ερεσια is illustrated in Bellori, Imag. 63, and in Gronov, Thes. 11, 34, but has now disappeared. She wears a headdress consisting of a sakkos bound twice round her head, and thick shoulder supports. Apparently not ancient.”

This opinion was followed by David A. Campbell’s 1982 Loeb edition of Sappho (p. 13, note 1). So, if they are right, then the origin of the Capitoline Sappho is still a mystery.

Sources:

Huelsen, Ch. “Die Hermeninschriften beruehmter Griechen und die ikonographischen Sammlungen des XVI. Jahrhunderts.” Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archaeologischen Instituts, Romische Abteilung. Bullettino dell’Istituto archeologico germanico, Sezione romana 16 (1901), 123-208 (at p. 199)

Jones, H. Stuart. A Catalogue of the Ancient Sculptures Preserved in the Municipal Collections of Rome: The Sculptures of the Palazzo dei Conservatori. Oxford: Clarendon, 1926.

Mandowsky, Erna and Charles Mitchell. Pirro Ligorio’s Roman Antiquities: The Drawings in MS XIII. B 7 in the National Library of Naples. London: Warburg Institute, 1963.

Ernst Platner, Ernst and Ludwig Erlichs, Beschreibung Roms: Ein Auszug Beschreibung der Stadt Rom. J.G. Cotta’scher Verlag, 1845.

Online record on the website in the Capitoline Museum

While awaiting comments from those who know more about Sappho and sculpture than I:

a) Is it coincidence that EPE might be the first erased letters?

b) Are there other erasures in that collection?

c) This reminds me of the statue of Hippolytus of Rome, or of someone, with his, or (partly?) some other’s works listed…if I remember correctly.

With regard to c), yes, the so-called Hippolytus was another statue first recorded by Ligorio around 1550, I think.

Earlier this year a different sculpture (confiscated in Antalya in 1972) was announced by Prof. Havva İşkan Işıkas as representing Sappho. It resembles the Munich Sappho (maybe a copy of one by Silanion?) more so than the one pictured above.

https://www.dailysabah.com/life/history/antalya-museums-portrait-sculpture-determined-to-be-sappho-of-lesbos

And then there’s the issue of whether anyone in Classical antiquity would have misspelled Σωκράτης as Σοκράτης.