One of the many events called off in the general shut down of activities last month was a meeting at the University of Agder associated with The Lying Pen of Scribes project, On the Origin of the Pieces: The Provenance of the Dead Sea Scrolls. I was scheduled to present a paper called “From the Outside, Looking In: Some Questions from a Novice Regarding the Contents of Qumran Cave 1.” I had been looking forward to having the experts answer some of my (potentially silly) questions about the earliest Dead Sea Scrolls to appear on the market. But since I couldn’t do it in that forum, I’ll pose my questions here over a couple posts.

My questions concern some of the most famous of all the Dead Sea Scrolls, the seven scrolls that were the first to appear on the antiquities market in 1947:

Rule of the Community (1QS)

The Habakkuk Pesher (1QpHab)

The Great Isaiah Scroll (1QIsaa)

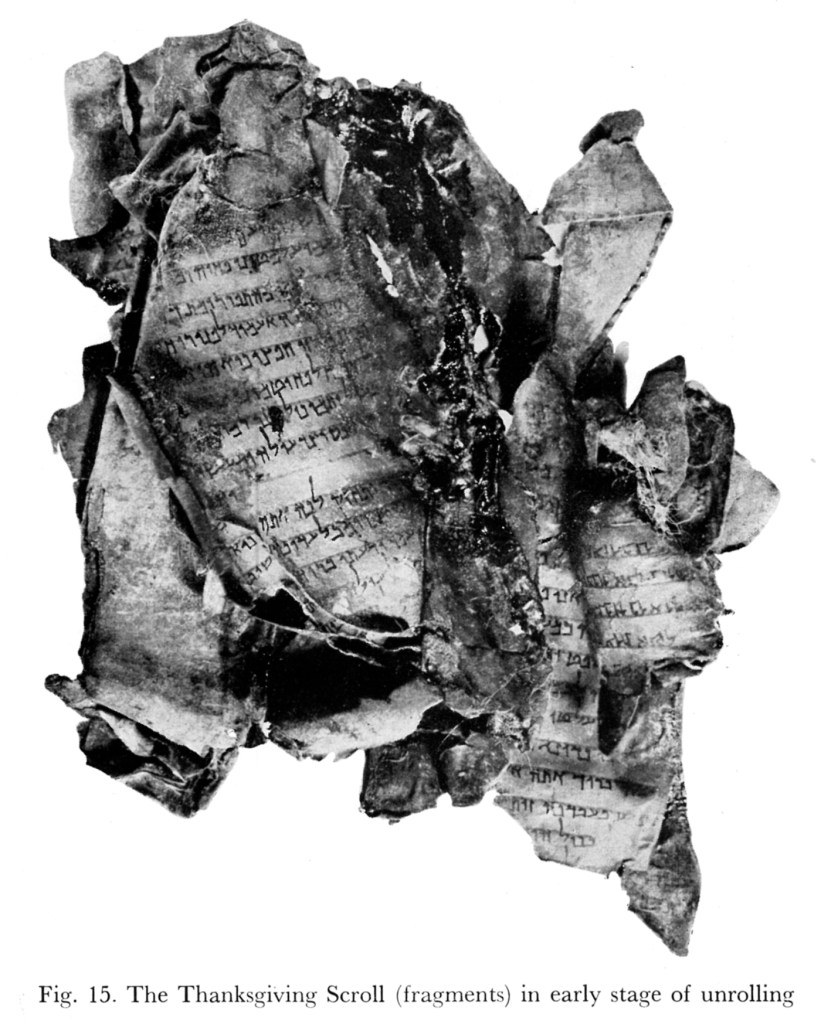

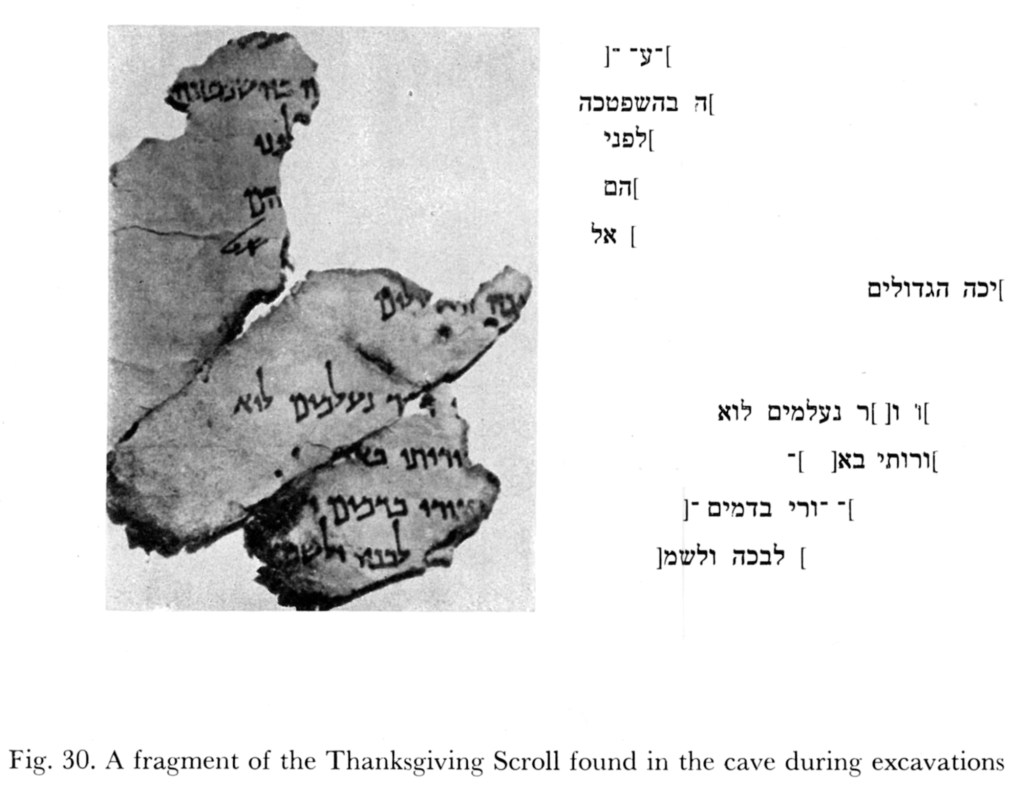

The Thanksgiving Hymns (1QHa)

The War Scroll (1QM)

A second copy of Isaiah (1QIsab)

The Genesis Apocryphon (1QapGen)

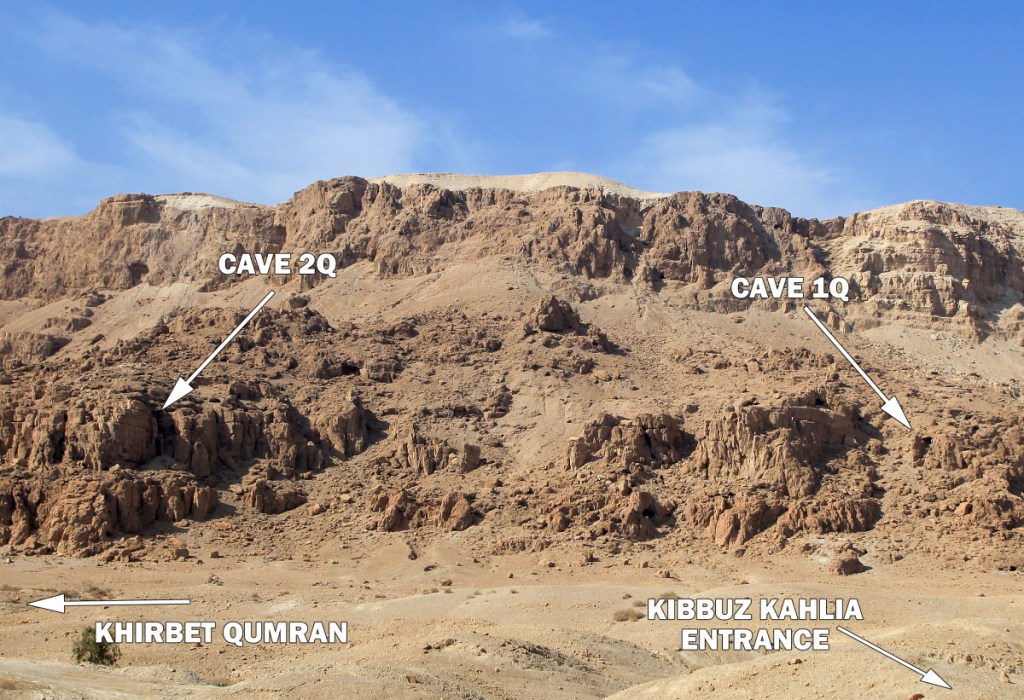

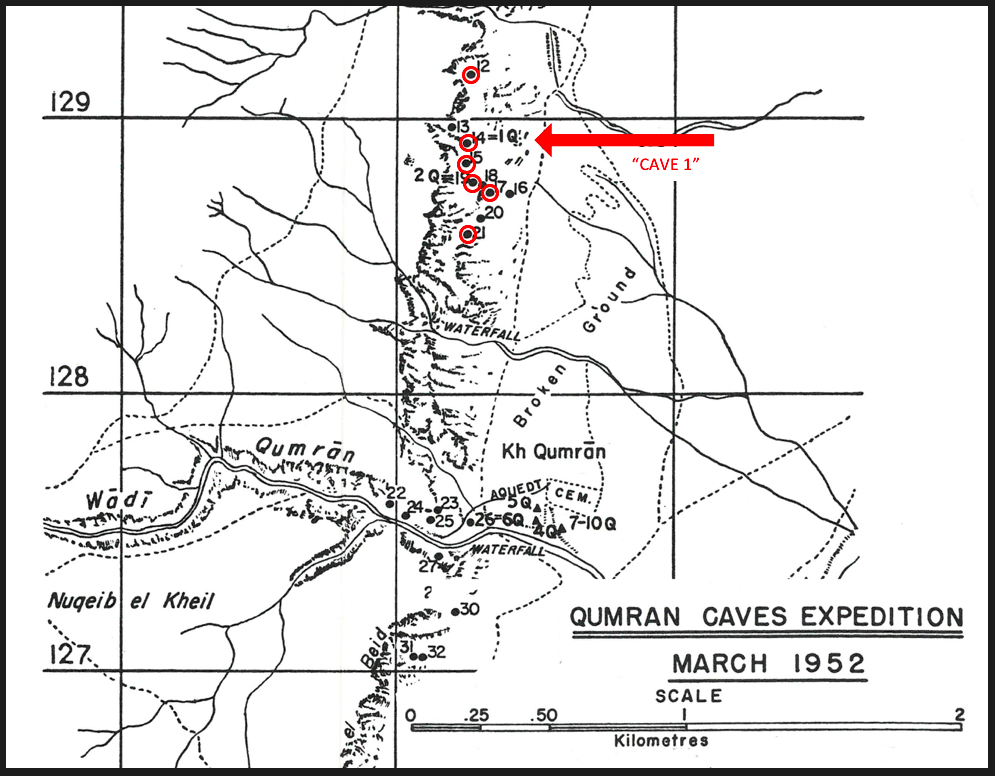

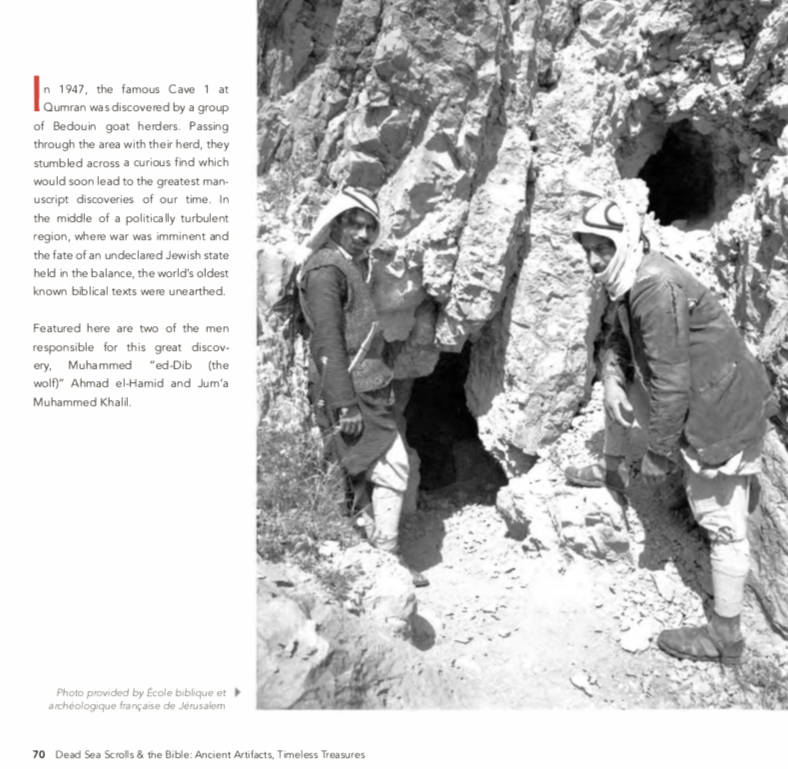

These pieces are regularly described as coming from “Cave 1,” a cave first identified and excavated in early 1949 by Father Roland de Vaux, director of the École Biblique in Jerusalem, at the request of Gerald Lankester Harding, director of the Antiquities Department of Jordan.

My overarching question is: How many of the manuscripts can actually be archaeologically connected to the the space now known as Qumran Cave 1? As best I can tell from the literature, the excavators of Cave 1 found portions of only one of these manuscripts, the War Scroll, in the cave (1Q33).

If I understand the scholarship correctly, none of the other six manuscripts have a physical link to the materials actually excavated by archaeologists. This raises the question of which of these manuscripts travelled together on the antiquities market? (Potentially, though not necessarily, manuscripts that circulated with the War Scroll could also have a connection to the same find spot.)

The War Scroll, the Thanksgiving Hymns, and 1QIsab were bought by Eleazar Sukenik in November and December of 1947. The Community Rule, the Habakkuk Pesher, the Great Isaiah Scroll, and the Genesis Apocryphon were sold in July of 1947 to Mar Samuel of St. Mark’s Syrian Orthodox Monastery. So, there appear to be two groups of scrolls. But there seems to be some question regarding to which of these two groups the Genesis Apocryphon belongs. Mar Samuel acquired it, but it is sometimes said to have been associated with the other group of scrolls on the market.

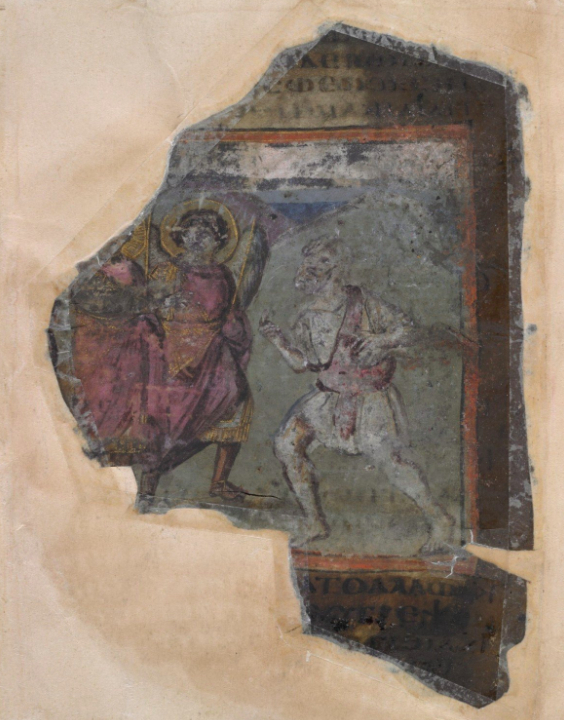

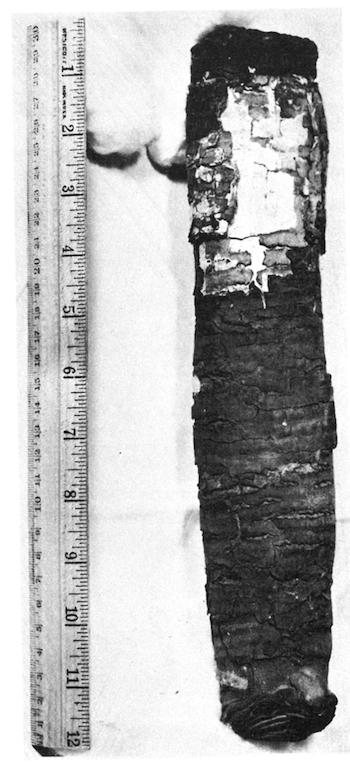

Genesis Apocryphon before unrolling; image source: Athanasius Yeshue Samuel, Treasure of Qumran: My Story of the Dead Sea Scrolls (Hodder and Stoughton, 1968), p. 165

The most thorough treatment of the assemblage from Cave 1 is a really rich and informative article by Joan E. Taylor, Dennis Mizzi, and Marcello Fidanzio. Regarding these two groups of manuscripts, the authors write (p. 301):

“At the same time, the Bedouin famously removed and sold on two lots of manuscripts, well preserved in jars they opened: the first one being the great Isaiah Scroll, the Pesher Habakkuk, and the Community Rule/Serekh ha-Yaḥad (1QIsaa, 1QpHab, and 1QS), and the second lot being the Genesis Apocryphon, the Rule of the Congregation, the second Isaiah Scroll, and the Hodayot Scroll (1QapGen ar, 1QSa, 1QIsab, and 1QHa) (see Fields 2009, 23-113).”

[[Sidenote: I’m a little confused by the absence of the War Scroll (1QM) from their list and the presence of the Rule of the Congregation (1QSa). I think this must be an error?]] So, the Genesis Apocryphon (1QapGen) is grouped with the Sukenik rolls rather than the other scrolls with which it was sold to Mar Samuel. The sources cited for this information are the first two chapters of Weston Fields, The Dead Sea Scrolls: A Full History: Volume One, 1947-1960 (Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2009).

Fields mentions this division of manuscripts on several occasions. Unless I miss something, the only time he cites an actual source is on p. 29:

“In the meantime, probably May-June 1947, Jum’a [that is, Jum’a Muhammed Khalil, one of the initial looters of the first scrolls] returned to the cave (or perhaps another cave, a question we take up later) with George [Isha’ya Shamoun, a Syrian orthodox Christian], and removed four more scrolls. Three of these they sold to Faidi Salahi, the Bethlehem antiquities dealer who had seen the first three. Three of these latter four were later bought by Professor Sukenik: the second Isaiah Scroll (Isaiahb), the War Scroll, and the Thanksgiving Scroll.41 The fourth was kept by Kando (Genesis Apocryphon, an Aramaic work in which the major characters of Genesis retell their own stories in the first person).42 It should be noted, therefore, that the Genesis Apocryphon belonged to the second set originally; it was acquired only later by the Metropolitan Samuel from Kando, and became associated with the first set (Isaiaha, the Manual of Discipline, and the Habakkuk Commentary) from the time they were shown to [John C.] Trever onward.”

The relevant endnotes would seem to be 41 and 42:

“41. Known from the beginning as ‘Thanksgivings,” plural or Hebrew Hodayot(h). I have chosen to use ‘Thanksgiving,’ in the collective sense of a scroll characterized by songs of thanks.

42. William Brownlee, ‘Foreword,’ in A. Y. Samuel, Treasure of Qumran, 12.“

The first note is not helpful. The second at least provides a lead. But, if we check p. 12 of the “Foreword” to Mar Samuel’s Treasure of Qumran, we find no mention at all of the discovery or purchase of the Genesis Apocryphon. When Mar Samuel himself writes about his major purchase later in the book, there is no indication of a different origin for the Genesis Apocryphon. So, what is the source for this grouping?

The answer seems to be found in John C. Trever’s book, The Untold Story of Qumran (1965). Trever had access to interviews with the alleged finders and the sellers of the scrolls conducted in the early 1960s. These interviews allowed him to reconstruct the events in this way (p. 106):

“In the meantime [between April and July 1947], having been urged by Metropolitan Samuel and Kando, Isha’ya persuaded the Bedouins, Jum’a and Khalil Musa, to take him to the cave. According to Jum’a (see Appendix I), the three of them went together in a taxi from Jerusalem to the point where the Dead Sea road branches from the Jericho road. From there they hiked for an hour to reach the cave. Nothing seems to have been taken from the cave on that visit, but Jum’a said that before they left Isha’ya made a cairn of rocks to mark the site. Some weeks later Jum’a met Isha’ya and Khalil Musa in the Bethlehem market place, and they were carrying two more scrolls from the same cave. Khalil Musa, when interviewed independently,27 agreed that he went a second time to the cave with Isha’ya but asserted that they secured four scrolls from under the debris on the floor of the cave at that time.28

These four scrolls were taken to Kando, who has confirmed the fact that four scrolls were brought to him by Isha’ya and Khalil before any scrolls had been sold to St. Mark’s.29 Kando kept only one of this group, however, as payment for the advance he had made to Isha’ya on expenses for the two trips to the cave.30 Khalil Musa and Jum’a wanted to keep the other scrolls since, as Kando put it, ‘they were partners’ in the deal. It seems likely that the scroll which Kando secured at that time (probably in May or June 1947) was the Syrians’ ‘Fourth Scroll,’ now called the Genesis Apocryphon’ (1QApoc).31“

The story seems fairly straightforward. In the footnotes, however, we get the actual (somewhat messy) data: p. 196, note 28: “Although in the interviews of November 24-25, 1961, Jum’a indicated that this [his trip back to the cave with Isha’ya] and a subsequent visit to the cave took place after the sale of the first scrolls to St. Mark’s Monastery (i.e. after July 19, 1947),” which would mean the Genesis Apocryphon would belong to the first group of scrolls Jum’a brought to Kando (1QS, 1QpHab, and 1QIsaa). In addition (p. 197, note 31), Kando, when presented with a photograph of the Genesis Apocryphon roll, “was quite certain that it was one of the scrolls which he delivered to Metropolitan Samuel. He seemed to think, however, that it was one of the scrolls that Jum’a had brought on his first visit.” Again, a primary figure in the story associates the Genesis Apocryphon with the first set of scrolls. Trever ably explains away these statements in light of other interviews and a later, revised statement by Jum’a.

What can we say at the end of the day? If Trever’s reconstruction is right, then, in addition to the second Isaiah Scroll (1QIsab), and the Hodayot scroll (1QHa), the Genesis Apocryphon might also have been found along with the War Scroll (1QM), which is archaeologically connected to Cave 1. But it seems to me worthwhile to note just how delicate this whole reconstruction is.

So, my question is: Am I missing any crucial evidence here?