I’ve just finished reading Roberta Mazza’s excellent new book, Stolen Fragments: Black Markets, Bad Faith, and the Illicit Trade in Ancient Artefacts (Stanford: Redwood Press, 2024).

This is a well organized and highly readable book. It tells a story–equal parts entertaining and disturbing–about a cluster of related topics: the collection of manuscripts and artifacts gathered by Hobby Lobby and the Museum of the Bible, Professor Dirk Obbink’s publication of an unprovenanced papyrus of Sappho, the sale and publication of dozens of so-called Dead Sea Scrolls that turned out to be forgeries, and the theft of over a hundred Oxyrhynchus Papyri from the collections of the Egypt Exploration Society held at the University of Oxford.

For those who may not have followed these stories, Roberta Mazza has been one of the main critical voices within the field of papyrology calling for increased vigilance about issues of provenance, and she has been relentless in focusing the discipline’s attention on the damaging role of the illicit antiquities market. Her blog, Faces & Voices, was a driving force in uncovering many of the scandals discussed in this book. Yet, there was a stretch of time between 2015 and 2021 when she was a trustee of the Egypt Exploration Society, which meant, as she explains, “I had to refrain from public comments (which was a true pain for me).” So it’s now quite eye-opening to have her account of what was going on behind the scenes during that time.

There has been some solid journalism on these topics over the years: The first broad overview was by Candida Moss and Joel Baden in their book, Bible Nation (2017). Then as the story developed, there were two very important long-form investigative articles: Charlotte Higgins’ piece in The Guardian (January 2020) and Ariel Sabar’s article in The Atlantic (June 2020). Mazza’s Stolen Fragments builds on all these earlier works, fills in gaps, and presents the most thorough and up-to-date treatment of the whole messy affair, with an epilogue that brings readers up to the spring of 2024.

In the course of narrating the intertwined stories of Hobby Lobby, the Sappho papyrus, the fake Dead Sea Scrolls, and the stolen Oxyrhynchus papyri, Mazza makes a larger case that scholars who work with manuscripts have too often been complicit in the illegal trade in antiquities by publishing unprovenanced artifacts. So, while it is interesting to see Mazza trace out the network of dealers, collectors, and yes, scholars, whose names appear repeatedly in connection with the trade of forgeries and/or stolen items (Lee Biondi, James Charlesworth, Bruce Ferrini, Craig Lampe, Dirk Obbink, Andrew Stimer, and others), Mazza’s aim goes beyond these infamous big names to the larger academic field of papyrology and the questionable practices it continues to tolerate.

There is a palpable urgency in Mazza’s writing, and for good reason. Mazza documents the ongoing problem of looting in Egypt, and her narrative highlights the connections between looting, the trade in unprovenanced artifacts, and academics who work on unprovenanced pieces. Stolen Fragments will become a a key reference point in these discussions.

The book is written in a way that will be accessible to a wide readership (I’ll be assigning it to students), but she also includes details that will also be useful to specialists (the notes at the end of the book lead to many interesting pathways). I’ve followed all these stories pretty closely over the years, and there were surprises even for me. I won’t give them all away, but here are two that jumped out at me.

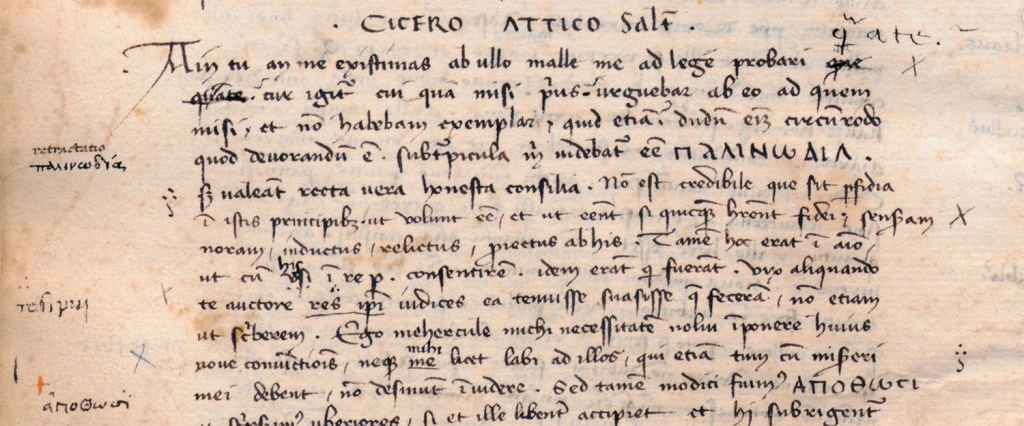

Throughout this episode, there has been a question about the location of the larger “P.Sapph. Obbink” fragment. It made an appearance in a television program with Prof. Obbink in 2015 and then disappeared from public view completely, as far I knew. In a 2020 article, Michael Sampson revealed that Christie’s had attempted to arrange a private treaty sale of the papyrus in 2015, but no further news about the papyrus was forthcoming. Mazza now reports that the papyrus was still at Christie’s in London when it was “seized by police in 2022” (p. 205). Readers will be relieved to learn that “Christie’s kept the papyrus’s expensive wooden box.”

Mazza also reports (p. 179) that all the pieces stolen from the Egypt Exploration Society have been recovered. This is very good news, but it’s surprising to me. The last EES announcement I recall on this topic came in 2021 (though it’s possible I missed later announcements). Anyway, in 2021, the editorial team in Oxford had identified about 120 missing pieces, of which 40 had been located in the collections of the Museum of the Bible and Andrew Stimer. One wonders if it was the ongoing police investigation into Prof. Obbink (now in its fifth year) that turned up some or all of these missing pieces.

There are, of course, still unanswered questions, as Mazza notes. At least some of these questions could be answered with fuller cooperation from other parties. From the side of Hobby Lobby and the Museum of the Bible: Now that they have repatriated most of their papyrus and parchment manuscripts, it would ideal if they made public all of their acquisition records relating to papyri, mummy masks, and other related artifacts, so that scholars can get a better sense of the shape of the antiquities trade in the US in those years when the collection was being built up (ca. 2009-2015). I would be curious, for instance, to learn more about the full extent of Prof. Obbink’s sales of antiquities to Hobby Lobby.

There is much more that could be said about this rich and exciting book. Fortunately, there will be a panel on it at the Annual Meeting of the Society of Biblical Literature in November in San Diego, with a great lineup of reviewers: Michael Holmes, Melissa Sellew, Sofia Torallas Tovar, and Liv Ingeborg Lied, with a response by Roberta Mazza.