When I was looking into the history of the Dead Sea Scrolls that are said to have been found in Cave 1Q a few years ago, I became interested in the early surviving videos and photographs of the scrolls and the excavators.

I recently came across an article in a popular magazine that I had missed until now. It’s a short piece by Gerald Lankester Harding that ran in Picture Post in August 1953. As the name of the magazine implies, the article is well illustrated with a series of photographs, for which the credit is given to Ronald Startup, a freelance photographer.

This 1953 photo shoot covers both the excavations at Qumran and the early work of sorting the fragments. I was surprised to see a photo of the “two shepherds” who are said to have been the first to find scrolls standing outside the entrance to Cave 1Q.

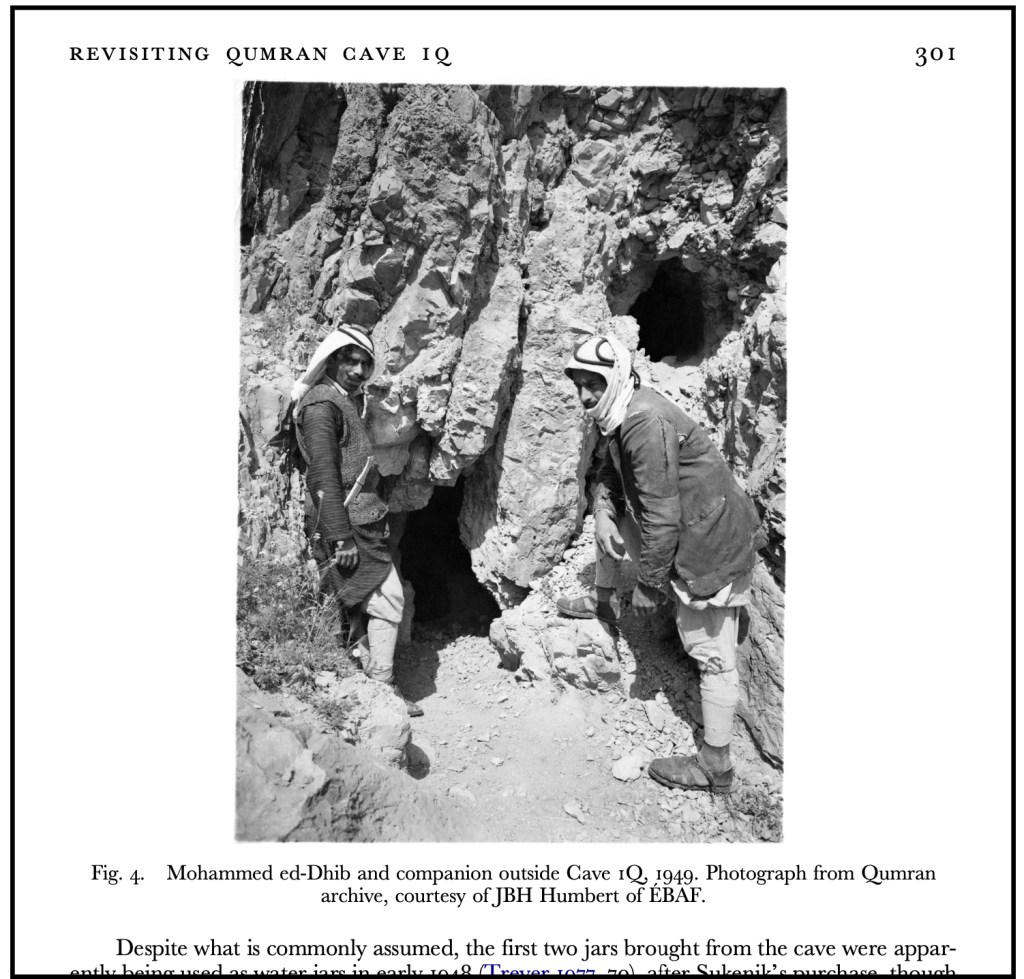

In this version of the image no identification is made beyond “these two shepherds.” When I have seen the image in other publications, one of the figures is identified as Muhammad ed-Dhib, the person usually credited with the initial discovery of the first three scrolls.1 I’m fairly sure that this 1953 publication is the earliest that I have seen this picture in print. What is odd is that when I have seen it in print elsewhere, the credit line is always the École biblique et archéologique française de Jérusalem. So, it seems that Ronald Startup, who took the rest of the photographs for this article, did not take this picture. This made me wonder who took it and when.

In the excellent 2017 article on Cave 1Q by Taylor, Mizzi, and Fidanzio, this picture appears as Figure 4, and it is given a date of 1949 in the caption.

But I don’t think this date of 1949 can be right. Cave 1Q was identified by archaeologists in late January 1949 and excavated between 15 February and 5 March 1949. As far as I know, that excavation was carried out by the Jordanian Department of Antiquities along with the École biblique and the Palestine Archaeological Museum (with the Arab Legion providing protection at the site). I don’t think there is any published reference to Bedouin teams in general or Muhammad ed-Dhib in particular being present at this cave at this time. Another story by Harding ran in the Illustrated London News on 1 October 1949. It makes no mention of identifying, much less photographing, the alleged discoverers of the first scrolls. I don’t think the identity of the alleged finders of the first scrolls were yet known to the scholars and archaeologists in 1949 (their identities were known by early 1953, when Harding mentioned “Mohammed edh Dhib and Ahmed Mohammed” by name in DJD I). [[Addendum 20 July 2024: I see that Harding did note in a 1949 article that the identity of the alleged finder of the scrolls had only just been discovered.2]]

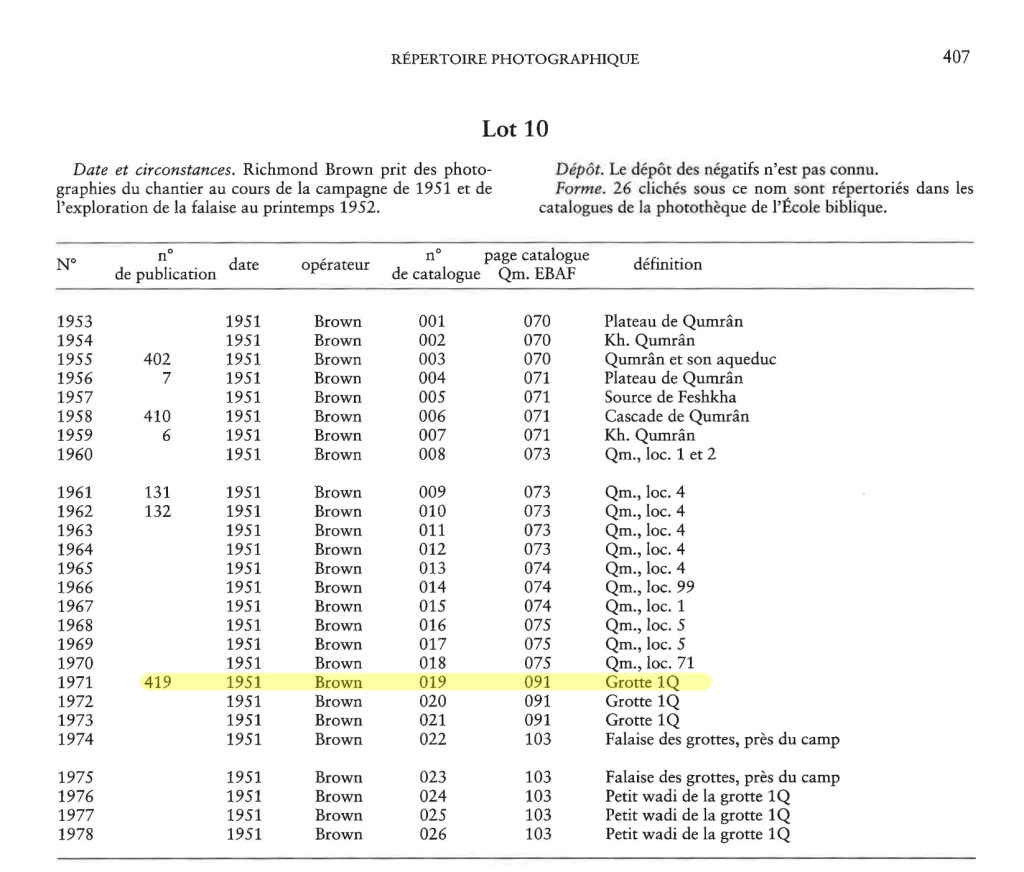

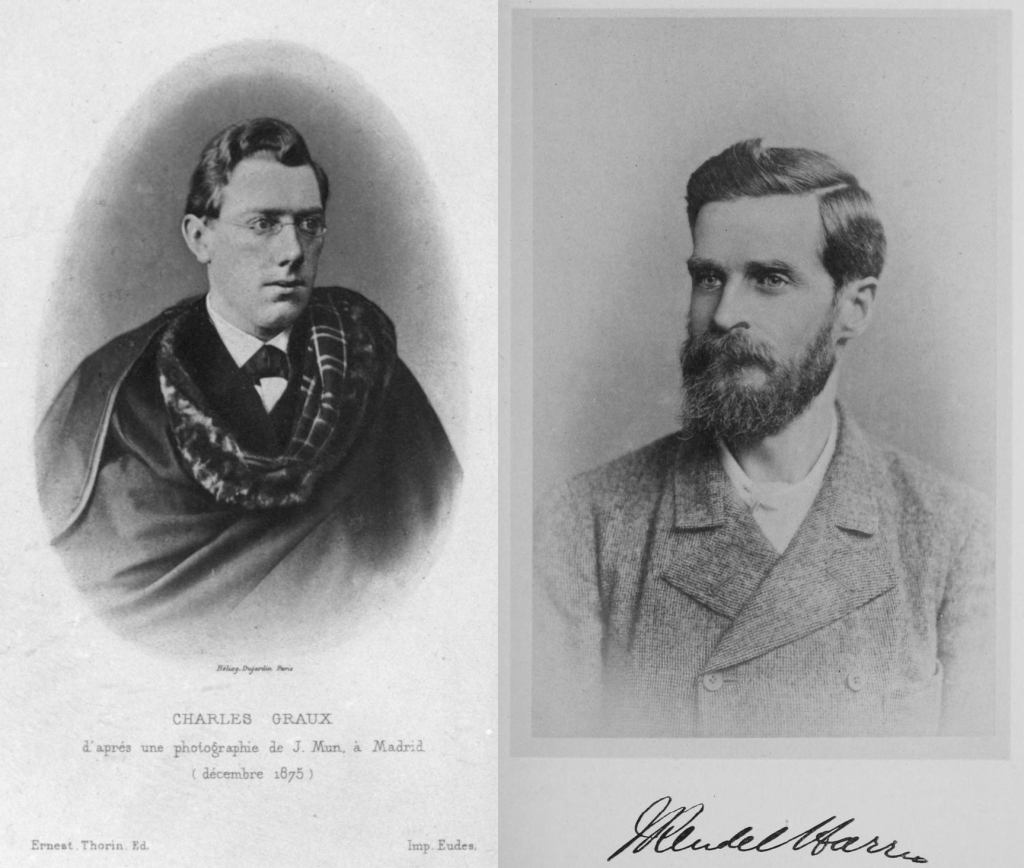

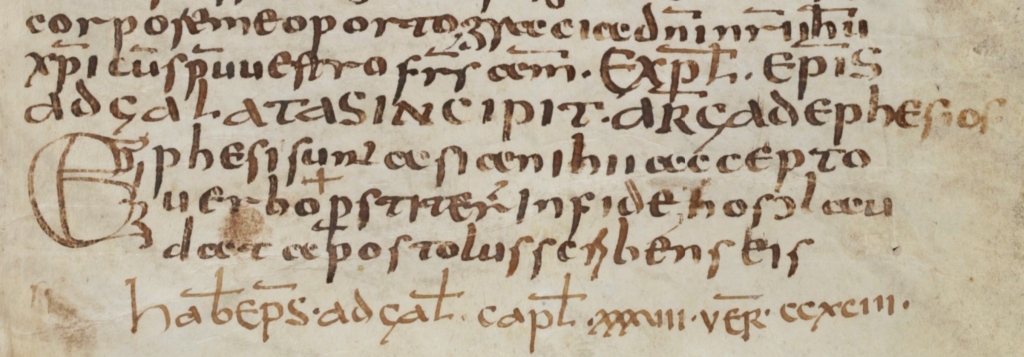

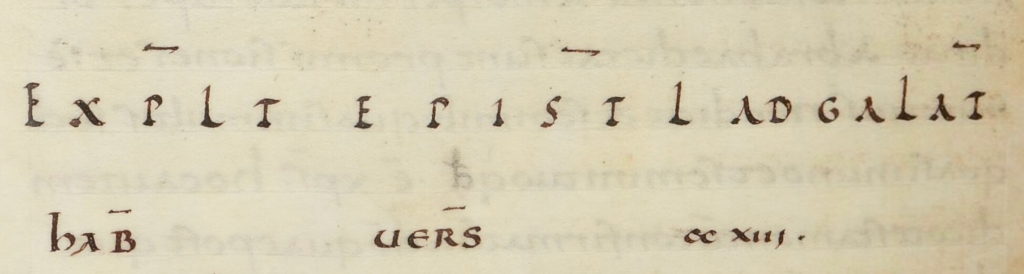

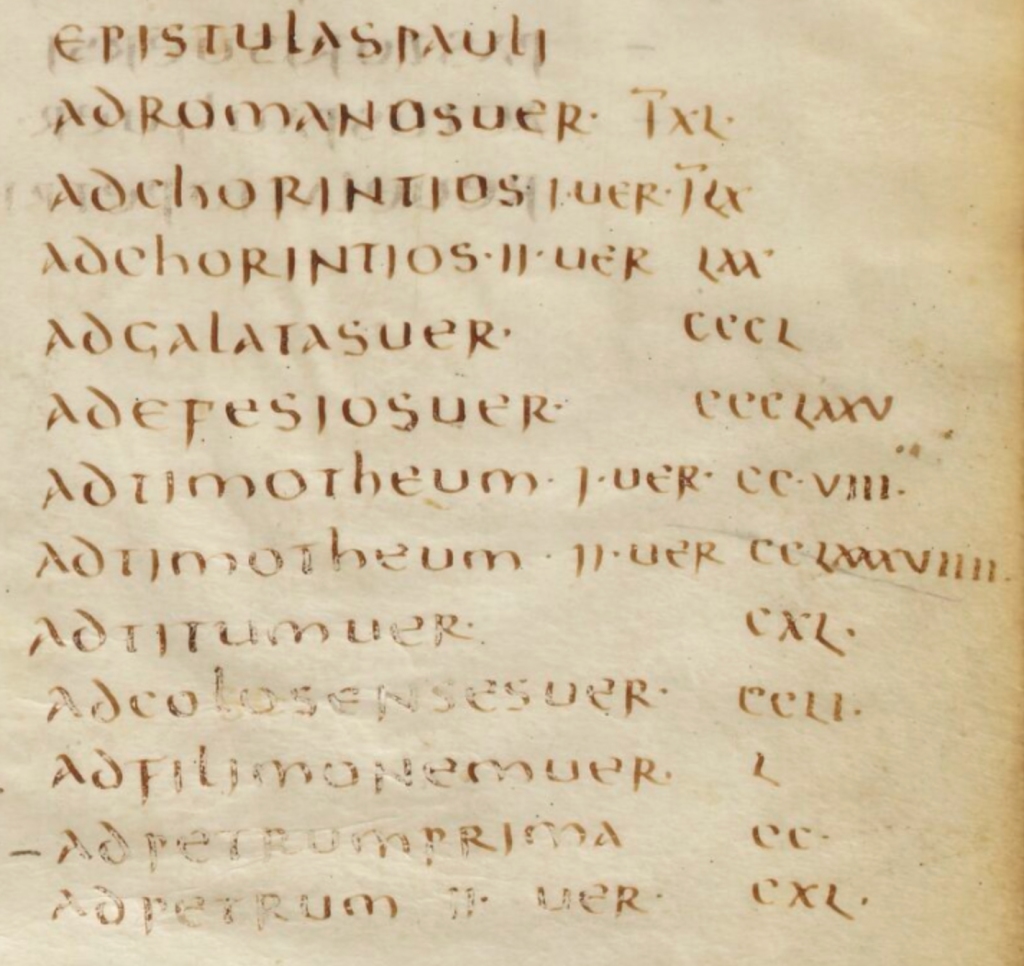

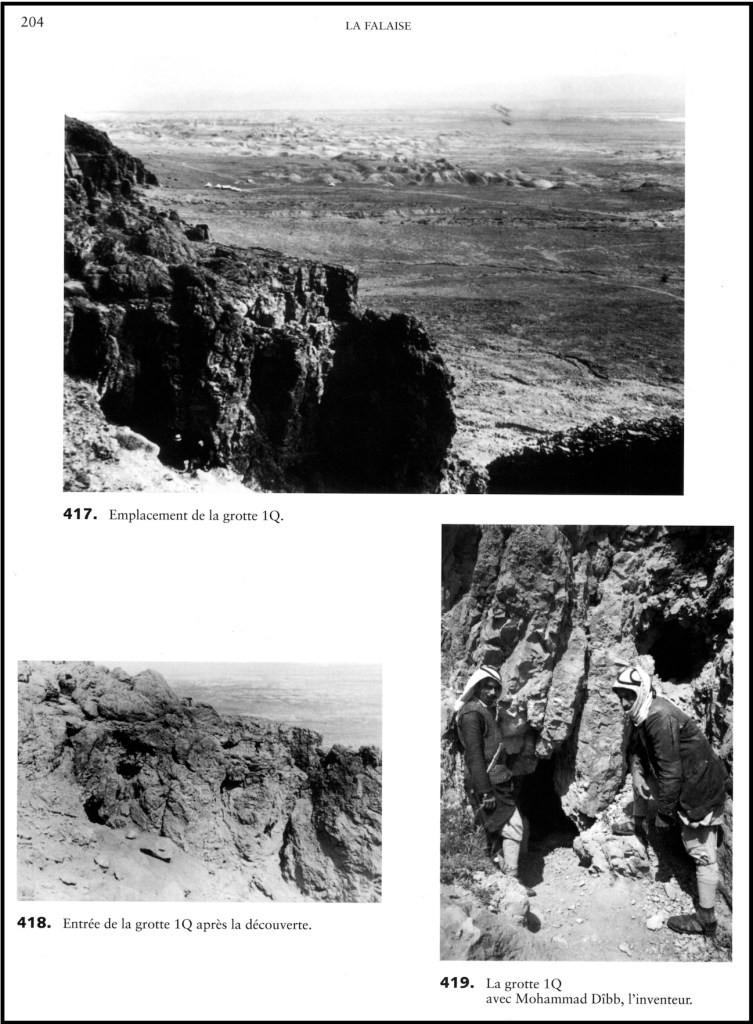

In any event, the source given for the photo, the École biblique et archéologique française, provides both the true date of the photo and a possible explanation for the date of 1949 given in the article. The first volume of the École biblique’s Qumran excavation report is a catalog of photographs related to the excavations. This picture appears in a series of photos of Cave 1Q as Figure 419:

The immediately preceding photo, Figure 418, was indeed part of a series of photos that Roland de Vaux took at Cave 1Q in 1949. But Figure 419 does not belong to that series. It was part of a different set of photos taken by Richmond Brown in 1951, as indicated in the photo log (p. 407 in the excavation volume):

I assume this is the same person as “Mr. R. Richmond Brown” who took some of the infrared photos of the Cave 1Q scrolls. So that seems to answer the question of who took the photo and when.

But what was the occasion in 1951 that brought these Bedouin to Cave 1Q? During the excavations of Khirbet Qumran that began in November 1951 (and the expeditions to the caves in the area that commenced in 1952), the Bedouin played an important role. Scholars often portray the discovery of the scrolls as “archaeologists in a race against the Bedouin,” and while there is some truth in this characterization, it is also the case that de Vaux’s projects employed many Bedouin workers, including the man identified as Muhammad ed-Dhib.3 When discussing William Brownlee’s proposal about a different identification of the location of the discovery of the first scrolls, John Trever mentioned that de Vaux and Muhammad ed-Dhib had at some point been together at Cave 1Q:

“I discussed the matter with Father R. de Vaux at the École Biblique in Jerusalem, and he told of sitting with adh-Dhib on a large rock within a few feet of the entrance to Cave I and listening to his account of the discovery.”4

I wonder if this photo from 1951 is a snapshot from that meeting, and I wonder if the 1953 Picture Post publication of this photo really is the first published image of Muhammad ed-Dhib.

Looking more closely at this photo also raises some questions for me about other photos of the alleged discoverer of the first scrolls. But that will wait for another post.

- Trever identifies the full name of this person as “Muhammed Ahmed el-Hamed, whose nickname is ‘Edh-Dhib’ ” (Trever, The Untold Story, 103). Frank Cross called him “Muḥammed edh-Dhîb Ḥassan” (Frank M. Cross, “The Discovery of the Samaria Papyri,” BA 26 [1963] 109–21, at 114 n. 4) ↩︎

- Harding wrote, “Up to the time of writing the original finder, who must be a goatherd, has not been located,” but in a footnote added before the article went to press, Harding reported the following: “Since writing this, Mr. Saad, Secretary of the Palestine Museum, has had an interview with the goatherd.” See Gerald Lankester Harding, “The Dead Sea Scrolls,” Palestine Exploration Quarterly 81 (1949) 112-116, at 112. ↩︎

- Roland de Vaux, “Les manuscrits de Qumrân et l’archéologie,” RB 66 (1959) 87-110, at 89. ↩︎

- John C. Trever, “When was Qumrân Cave I Discovered?” Revue de Qumrân 3 (1961) 135-141, at 140. ↩︎