Over on his blog, Larry Hurtado has posted a detailed review of God’s Library. Early on in the book, I mention three of the main scholars who paved the way for those of us working on early Christian manuscripts today: Roger Bagnall, Harry Gamble, and Larry Hurtado. So I’m very gratified to see that Hurtado’s review is largely positive.

I’ll take this opportunity to follow up on Hurtado’s assessment of one of my more sweeping criticisms of the use of palaeography to assign precise dates to Greek literary manuscripts of the Roman era. Hurtado writes as follows:

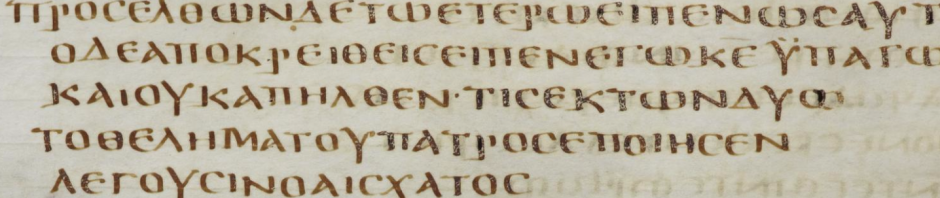

“Nongbri expresses some hesitation about the dates of these two codices [the Chester Beatty Gospels and Acts codex, P45, and the Beatty codex of the Pauline epistles, P46], however, because “our corpus of datable samples in taken almost entirely from rolls,” a format that was “largely supplanted [in general usage for Christian and non-Christian manuscripts] by the codex by the end of the fourth century” (138). True, but whether roll or codex “documentary” texts tended to have dates written by the copyist, and so they can still be used to help us make comparisons with undated literary texts such as the NT writings. Perhaps I’m missing something, therefore, but I don’t find his argument persuasive.”

The book contains a somewhat more detailed discussion of this point on pages 71-72, but I want to take some time here to try to spell out the argument even more fully: When trying to use palaeography to assign a date to an undated literary manuscript, the general preference is to try to use other (dated) examples of literary manuscripts as the main points of comparison, as opposed to non-literary documents (letters, deeds, wills, receipts, etc.–everyday writing). Securely dated documents that happen to be written in literary hands are regarded as very useful reference points, but some highly respected palaeographers have expressed a preference for giving more weight to literary manuscripts in these exercises. Eric Turner makes this point in his Greek Manuscripts of the Ancient World (2nd ed., 1987, pages 19-20):

“To obtain a more precise result [when assigning a palaeographic date to a manuscript], it will be necessary to find a dated or datable handwriting which the piece under examination resembles. . . . Confidence will be strongest when like is compared with like: a documentary hand with another documentary hand, skilful writing with skilful, fast writing with fast. Comparison of book hands with dated documentary hands will be less reliable. The intention of the scribe is different in the two cases; besides, the book-hand style in question may have had a long life.”

According to palaeographers like Turner, then, it is preferable to compare bookhands with other (dated) bookhands. Given that stance, it is crucial to note that the pool of securely dated or datable samples of bookhands contains almost no codices. There is good reason for this: Rolls have a blank side that can be reused. The back of a dated documentary roll can be reused for a literary text, and the back of a literary toll can be reused for a dated document. Codices, with their leaves inscribed on both faces, are not ideal for reuse in this manner. Why is this lack of codices in the pool of dated comparanda a problem? It is widely acknowledged that before the third century CE rolls rather than codices were the main vehicle for the transmission of literature. Over the course of the third and fourth centuries, the codex overtook the roll as the chief medium for literature. Using the Leuven Database of Ancient Books (LDAB), we can get a rough sense of the change over time. For the first century, codices account for virtually zero percent of surviving books. Codices make up about 5% of books assigned to the second century, about 24% of books assigned to the third century, about 79% of books assigned to the fourth century, and about 96% of books assigned to the fifth century. The major shift seems to have occurred over the course of the third and fourth centuries.

Now, we know that particular “styles” of writing are not exclusive to particular formats. So, for instance, we have plenty of examples of, say, “the severe style” preserved on rolls and plenty of examples preserved in codices. But–here’s the rub–the securely dated samples are almost always rolls (for the reasons of ease of reuse outlined above). Thus our pool of datable samples of literature tend to be on the “earlier” format (rolls), but this pool of samples is used to assign dates both to undated rolls and to undated codices. So, if a codex were copied in the late third or early fourth century using “the severe style,” we would have no way of correctly assigning the date by means of palaeography because our pool of datable samples trickles off at the period at which the codex replaced the roll as the primary vehicle for the transmission of literary texts.

In the case of codices, then, overreliance on the corpus of datable literary manuscripts (i.e., reused rolls) will cause the dates of the codices as a group to skew early. In all likelihood, some codices are properly dated to the second and early third centuries, but just as certainly, some will have been dragged improperly into that period by comparison with a set of data (reused rolls) that basically ends during the third century. When trying to assign dates to literary codices, we should therefore pay special attention to dated documents of the later third and fourth centuries that are written in something approaching literary hands. The usefulness of such documents for establishing dates of undated manuscripts is generally recognized, but they become even more important in light of this observation about the corpus of datable literary manuscripts.

I’m convinced this is a neglected but crucial point, and so I’ve expanded the argument in an article with a lot more data to back up my generalizations, but it has been in the publication queue for over a year now. I hope to see it out sooner rather than later, but some things are out of my control. . .

Thanks again to Larry Hurtado for the thorough review of the book.

I agree with your analysis and assessment, Brent. Thank you for your thorough treatment and clarity.

Reblogged this on Talmidimblogging.