I am in the process of working my way through videos of the lectures associated with the “Passages” travelling exhibition of Green Collection. At the prompting of David Bradnick who is also engaging in this pastime, I jumped ahead to “Season 2,” the group of lectures given in Atlanta in 2012. David mentioned that Scott Carroll had interesting things to say about some Christian manuscripts and also the Green Collection Sappho Papyrus. It is the latter that will be the topic of this post.

Just to refresh: In February of 2014, an article in The Times announced that an anonymous owner “had material from an ancient Egyptian burial in his possession. He’d noticed that scraps of the cartonnage (the Egyptian equivalent of papier-mâché, made of recycled papyrus) bore the ghostly imprint of writing.” He contacted Oxford professor Dirk Obbink, who “prised the layers of shredded papyrus apart” and discovered a sizable fragment containing several lines of the Greek poet Sappho. Later, it became clear that the Green Collection also held additional fragments of the same papyrus roll of Sappho’s poems. Over time, however, the account of the origin of the Sappho papyrus changed quite dramatically. Here is the account of provenance given by Dirk Obbink in a 2016 publication [[my comments in italics inserted in double brackets]]:

“As reported and documented by the London owner of the Brothers and Kypris Song fragment, all of the fragments were recovered from a fragment of papyrus cartonnage formerly in the collection of David M. Robinson and subsequently bequeathed to the Library of the University of Mississippi [[As I have pointed out in a previous post, this is mistaken; the University of Mississippi never owned the Robinson Papyri]]. It was one of two pieces flat inside a sub-folder (sub-folder ‘e3’) inside a main folder (labelled ‘Papyri Fragments; Gk’.), one of 59 packets of papyri fragments sold at auction at Christie’s in London in November 2011. . . The layers of the cartonnage fragment, a thin flat compressed mass of papyrus fragments, were separated by the owner and his staff by dissolving in a warm-water solution. The owner originally believed that he had dissolved a piece of ‘mummy’ cartonnage. But this turned out upon closer inspection of the original papyri not to be the case: none of the fragments showed any trace of gesso or paint prior to dissolving or after. . . . The piece of cartonnage into which the main fragment containing the Brothers and Kypris Songs was enfolded (bottom to top, along still visible horizontal fold-lines, with the written side facing outwards) was probably domestic or industrial cartonnage: it might have been employed e.g. for a book-cover or book-binding. Some twenty smaller fragments removed from the exterior of this piece, being not easily identified or re-joined, were deemed insignificant and so traded independently on the London market by the owner, and made their way from the same source into the Green Collection in Oklahoma City.”

So, on this account it was not Dirk Obbink, but the anonymous London owner of the cartonnage who dissolved it and presented one large piece to Dirk Obbink to be published (as P.Sapph.Obbink). Other fragments of Sappho extracted from the cartonnage were sold by the owner (and extractor) of the papyri, and they eventually ended up in the Green Collection (P.GC inv. 105, frs. 1-4).

Now, let’s hear what Scott Carroll had to say about the Green Collection Sappho fragments back in 2012. After a “Passages” talk in Atlanta on the Dead Sea Scrolls given by Emanuel Tov, Scott Carroll gave some closing remarks, while holding up the Green Collection Sappho fragments as a prop:

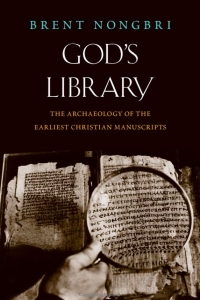

Scott Carroll holding up the Green Collection Sappho fragments in Atlanta in 2012

“I do have an example here of what he’s talking about with Corn Flake-type–these are not quite Corn Flake size. You can see here. There are 26 fragments of this text in Greek on papyrus. And, um, it came out of a mummy mask I dismantled a few weeks ago. Um, it is, they are texts. Of course for me, with my area of passion and scholarship–biblical texts are, are what I’m most interested in. But really, truly for classical scholars, this is, these are texts of the most elusive and sought-after of all Greek authors, and that’s the writing of the, uh, female poet Sappho.”

So, according to Carroll’s version of events, he himself extracted the Green Collection’s Sappho fragments from a mummy mask. Now, several possibilities exist for reconciling these accounts:

- In his 2012 comments, Scott Carroll . . . misremembered that it was the anonymous London owner or Dirk Obbink who extracted the fragments that Carroll was holding in his hand.

- In the 2014 Times article, the author misstated who actually dismantled the cartonnage (the anonymous owner or Scott Carroll, rather than Dirk Obbink).

- In his 2016 publication, Dirk Obbink . . . misremembered that it was not the anonymous London owner but rather Scott Carroll or he himself who had extracted the Green Collection’s Sappho fragments from cartonnage.

- Scott Carroll was the anonymous London owner of P.Sapph.Obbink.

Number 2 would seem to be a distinct possibility in light of journalistic tendency to embellish stories. And in fact, David Meadows at rougeclassicism had already tentatively raised the possibility of number 4 based on other publicly available information (including Scott Carroll’s Facebook posts and Tweets) back in July of 2017. If it is in fact correct that Scott Carroll was the owner of P.Sapph.Obbink, two questions arise:

- Why would Dirk Obbink and Scott Carroll want to obscure that Carroll was the owner of the Sappho papyri?

- Is Scott Carroll still the owner of P.Sapph.Obbink?

And of course, questions about the ultimate origin of these papyri also remain unanswered: If these pieces are in fact “Robinson Papyri,” how did they come to be put up for auction in 2011? As best I can tell, the papyri were the property of Duke professor William Willis. He periodically donated pieces to Duke University but seems to have still owned several pieces at the time of his death. What became of them when he died? Can a path be traces from Willis to the 2011 auction?

Once again, some light could be shed on these matters if the Green Collection released information concerning from whom they purchased these papyri (or the cartonnage from which they were allegedly extracted).

[[Update 19 July 2019: I should also add still another contradictory account, this one from an article in The New Yorker that went online on 9 March 2015:

“One day not long after New Year’s, 2012, an antiquities collector approached an eminent Oxford scholar for his opinion about some brownish, tattered scraps of writing. The collector’s identity has never been revealed, but the scholar was Dirk Obbink, a MacArthur-winning classicist whose specialty is the study of texts written on papyrus—the material, made of plant fibres, that was the paper of the ancient world. When pieced together, the scraps that the collector showed Obbink formed a fragment about seven inches long and four inches wide: a little larger than a woman’s hand. Densely covered with lines of black Greek characters, they had been extracted from a piece of desiccated cartonnage, a papier-mâché-like plaster that the Egyptians and Greeks used for everything from mummy cases to bookbindings. After acquiring the cartonnage at a Christie’s auction, the collector soaked it in a warm water solution to free up the precious bits of papyrus.“

So, in this version, the anonymous “antiquities collector” (rather than Carroll or Obbink) is the one who allegedly separated the cartonnage.]]

Reblogged this on Talmidimblogging.

If we accept the London business man story, and putting together a timeline from various published sources, the Sappho fragments were:

a. sold as cartonnage to the London businessman (Nov. 28, 2011)

b. Obbink views cartonnage (late January 2012)

b. fragments dismantled from the cartonnage (?)

c. some fragments sold to the Green collection in Oklahoma City (?)

d. identified as Sappho fragments (?)

d. displayed by Carroll in Atlanta (Feb. 7, 2012).

All of this happened in about 2.5 months. Furthermore, the dismantling of the cartonnage, the selling of the fragments, their identification, and their display by Carroll happened within a matter of a couple of weeks. These Sappho fragments had quite a journey in a seemingly short period of time; some might even say extraordinary.

Given this unfolding of events, did Carroll identify these as Sappho fragments by himself or with help? And when were they recognized? Before the purchase? After the purchase? Given what we know about the Green’s purchasing practices, what is the likelihood that the Greens would buy them without being identified first? At what point did Obbink become involved with the Green Collection fragments? Obbink writes, “the first of the new fragments to be identified among the Green papyri (Sappho fr. 5) was achieved by means of a search of the tlg corpus on sequences of letters in the papyrus that were not anywhere extant previously in any manuscript or quotation.” Who did this search? Himself? And, when? This is interesting because Carroll already knew that these were Sappho’s writing by Feb. 7, 2012.

Another option, as Nongbri mentions above, is that Carroll was the anonymous owner. Considering this hypothetical, was Carroll profiting from both working for the Greens and the sale of papyri? Is this why the identity of the seller had to be kept anonymous?

In a 2015 BBC documentary, Sappho: Love and Life on Lesbos, Obbink discusses the dismantling of the cartonnage in significant, and perhaps curious, detail. Beginning at about min. 2:45, he states, “When the small pieces were humidified, they immediately started to peel off and the first thing that you could see underneath were then ends of the first three lines. The letters that my eye first focused on was the second to the last word of the first line, Charaxon, that’s a man’s name . . . . The only person we know in Greek antiquity who had the name Charaxos was the brother of the poet Sapho from the island of Lesbos. . . . It knocked my socks off.”

Wow! How interesting that Dirk Obbink also claims to have separated the cartonnage. And, yes, the compressed timeline between the auction in Nov. 2011 and Carroll’s display of the mounted fragments in Feb. 2012 does seem remarkable. Lots of questions.

Don’t forget some papyri such as the Galatians went Christie’s -> Istanbul -> eBay -> Green Collection.

If I understand Roberta Mazza’s work correctly, it is probable that the Galatians fragment was never part of the Christie’s lot (or the Robinson Papyri). It would be pretty shocking if a papyrus like that went unnoticed by Willis, who owned the Robinson Papyri. The convenient thing about the Sappho allegedly coming from cartonnage was that unassuming cartonnage may plausibly have been overlooked by Willis.

I’m no expert on these questions, but my provisional (maybe mistaken) impression is that University of Mississippi deaccessioned these papyri in the 1980s. And, after Dirk Obbink (DO) recognized Sappho text, while the London owner’s associates humidified the mass, he DO set about to trace previous sales of David M. Robinson mss, in case any of them had more Sappho, but did not recover any from that approach, a search that he kept sub rosa for some time. At some point DO became aware that the London businessman’s lot included bits that eventually later (than the Christies sale) had gone to the Green collection, and did include more Sappho.

(How ironic that, maybe, David M. Robinson, a Sappho expert, had unread Sappho verses for years, unbeknownst to him, for caution about opening.)

From DO Preliminary Version ZPE 2014 (archive.org): “Occasionally, in places, ink traces are obscured by spots of adherent material that appears to be light-brown gesso or silt, specs of which are also to be seen on the back.” The guess of gesso may have been influence by much mummy talk. Or silt, maybe. Or book binding paste or glue (adherent) or something else? Ideally, a sample would be preserved (and maybe was/is), in order to be characterized. Such would not necessarily add anything significant. But I recall a Qumran case in which a text was imprinted on a piece of marl. Hanan Eshel, therefore, doubted that it came, as claimed, from (natural) Cave 11, a higher (than Kh. Qumran) cliff cave, but that it more likely came from Cave 4, a lower (than Kh. Qumran) cave dug into marl. “A Note on 11QPs d Fragment 1,” Revue de Qumran 23/92 (2008) 529-31.

Pingback: More Early Christian Greek and Coptic Papyri in the Green Collection? | Variant Readings

Pingback: The Green Collection Mummy Masks: A Possible Source | Variant Readings

Pingback: Dirk Obbink, Scott Carroll, and Sappho | Variant Readings

Pingback: Harold Maker: An Ideal Provenance Distraction | Variant Readings

Pingback: A New Origin Story for the New Sappho | Variant Readings

Pingback: More News on Dirk Obbink and Sappho | Variant Readings

Pingback: News on the Newest Sappho Fragments: Back to Christie’s Salerooms | Roberta Mazza

Pingback: Important Developments with the New Sappho Papyrus | Variant Readings

Pingback: More on Dirk Obbink and the Provenance of the Sappho Papyrus | Variant Readings

Pingback: Fleecing a Discipline – Mycenaean Miscellany