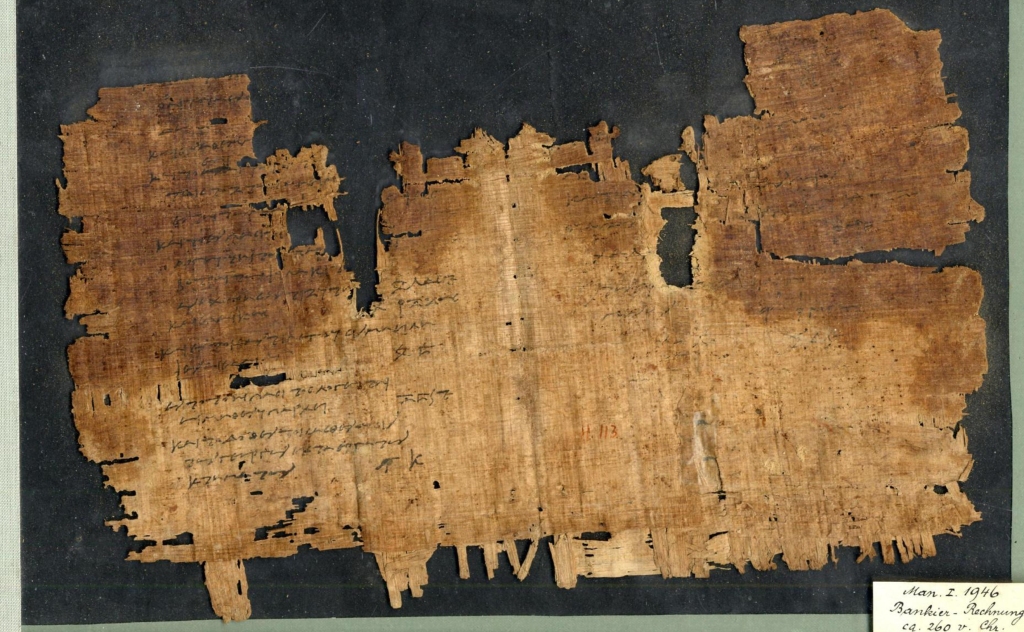

News reports coming out of Graz today suggest that a papyrus in the collection of the University of Graz may be the earliest surviving specimen of a bound book with pages, possibly as early as the third century BCE. It is a papyrus that was published way back in 1906, P.Hib. 113:

“The papyrus fragment (Graz, UBG Ms 1946), which measures only about 15 x 25 cm, has belonged to the University of Graz since 1904. Discovered during an excavation in the Egyptian necropolis of Hibeh (today El Hiba) south of Fayum (El-Fayoum), the fragment now belongs to a collection of 52 papyrus objects, some of which were used as so-called cartonnage for mummy wrappings in the Ptolemaic period (305-30 BC).”

Theresa Zammit Lupi, the head of conservation of the Special Collections of Graz University Library, noticed the presence of a thread, what appears to be a central fold, and holes along the central fold that could indicate binding. This announcement is potentially very exciting news for those of us interested in the early history of the codex, but the news release itself is a bit jumbled. The claims made about the earliest codices in the report seem somewhat confused. According to the press release,

“The earliest codices known to date with evidence of stitching in book form have been dated to 150-250 AD. Two such examples are located in the British Library (Add MS 34473) and the Chester Beatty Library, Dublin (CBL BP II).”

British Library “Add MS 34473” isn’t a designation of a single manuscript. That inventory number covers several parchment manuscripts, none of which (to the best of my knowledge) has been assigned especially early dates. The possible exception might be parchment fragments of a codex containing works of Demosthenes filed under that inventory number (P.Lond.Lit 127, TM 59549), which are sometimes assigned a date as early as the second century CE. There is, however, a parchment codex fragment in the British Library that is generally assigned an even earlier date, British Library Papyrus 745, (TM 63267), which may be as old as the second or even the first century CE. Chester Beatty BP II is, of course, the single-quire papyrus codex of Paul’s letters better known to New Testament scholars as P46 (TM 61855), which has been assigned to a wide range of dates, from the late second century CE to the late third or fourth century CE. But it is generally thought that the earliest of the Beatty Biblical Papyri is the BP VI (TM 61934), the Numbers-Deuteronomy papyrus codex, which is usually assigned to the second or third century CE.

These small details aside, I am excited to learn more about this papyrus. It was reused for cartonnage, which gives us a reasonable terminus ante quem. But as far as I can see from the online images, there is no writing visible on the “back” side of the papyrus. There is writing on the right side of the “front” of the papyrus, but it is tough to decipher. It would be nice to see the whole thing subjected to multi-spectral imaging to see what is legible on the right side of the papyrus as well as the “back” side. If there is continuous text from the back to the front, that would be a nice confirmation that we do in fact have a very early codex here. I look forward to learning more about this piece!

I would like to posit a question if I may? If I were to take three sheaths of paper, fold them in the middle and insert inside each other to form a quire, then stitch the sections together, as a finished product I essentially have a booklet. But is this a codex? At what point does folded sheets gathered become a codex? Could this papyrus from Graz University be the front page of a booklet only and can it is so proved to have other associated pages written on both side be an actual codex?

Hi David,

Thanks for this observation and question. The issue of how we define codex is important, and I’ll dedicate a separate post to that.

Hi Brent

Looking forward to it.

Unfortunately, this is almost certainly not a codex. Mummy cartonnage commonly included sewing/stitching to hold it in place (cf Vandenbeusch, O’Flynn, Moreno, “Layer by Layer: The Manufacture of Graeco-Roman Funerary Masks” [2021] https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/03075133211050657). The Graz University conservator who is making the claim that it’s a codex, Dr. Theresa Zammit Lupi, is a specialist in French Renaissance manuscripts. It seems that papyrologists were not consulted before the claim was sent out to make headlines.

Pingback: What Do We Mean By “Codex”? | Variant Readings

Pingback: More Details on the Possible Codex at Graz | Variant Readings

Pingback: The Potential Early Papyrus Codex at Graz | Variant Readings