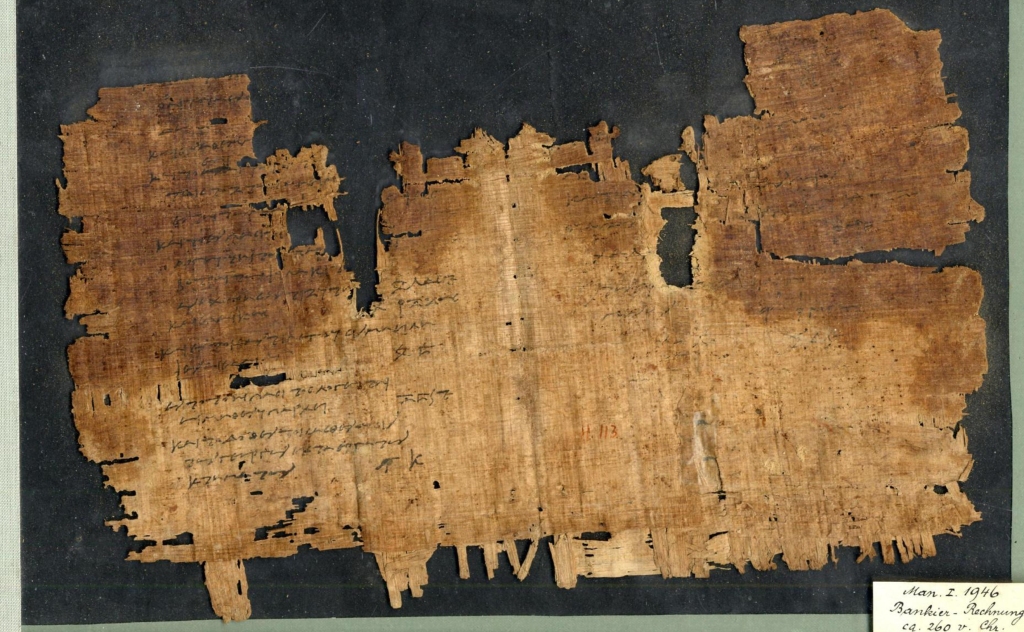

Back in June 2023, several news outlets picked up the story of “the Graz mummy book.” A team at the University of Graz led by Theresa Zammit Lupi had identified P.Hib. 113, a papyrus extracted from mummy cartonnage and published by Grenfell and Hunt in 1906, as a bifolium from a codex, a book with pages. This was big news because P.Hib. 113 can be dated with a reasonable degree of confidence to about the middle of the third century BCE. This is some three centuries earlier than most scholars have placed the development of papyrus and parchment codices.

Then in September, I noted that the team at Graz had posted a more detailed essay on the papyrus. This has now been summarized in an open-access report published in early 2024 in the Journal of Paper Conservation.

Earlier this week, a group of scholars that included specialists in papyrology, bookbinding, and conservation met in Graz to examine the papyrus. Together with the Graz team, we took a close look at several different aspects of this papyrus. It was an eye-opening experience.

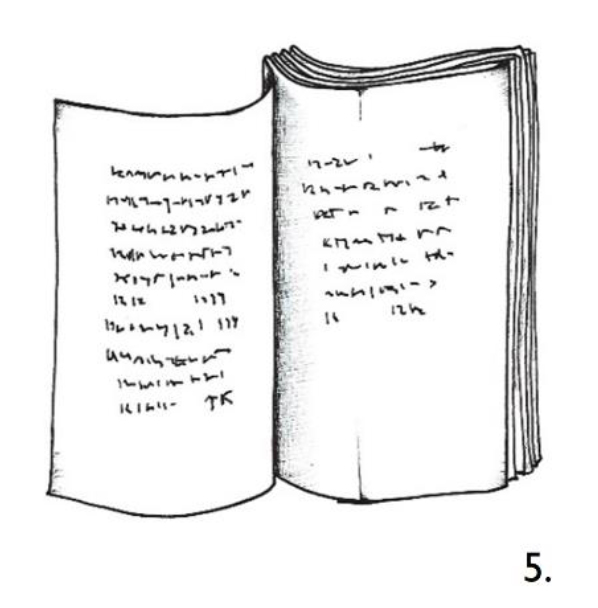

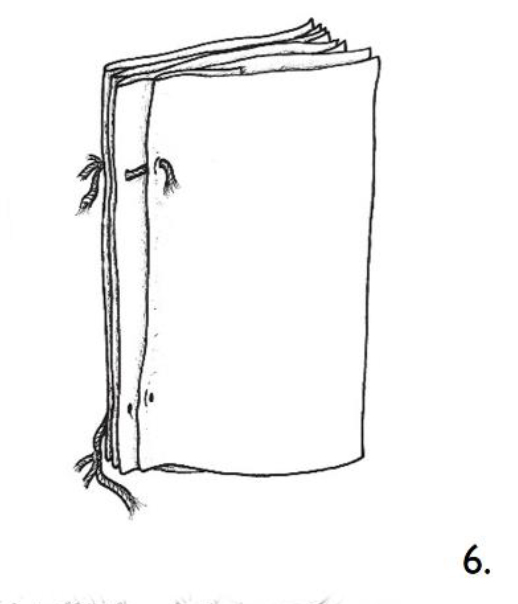

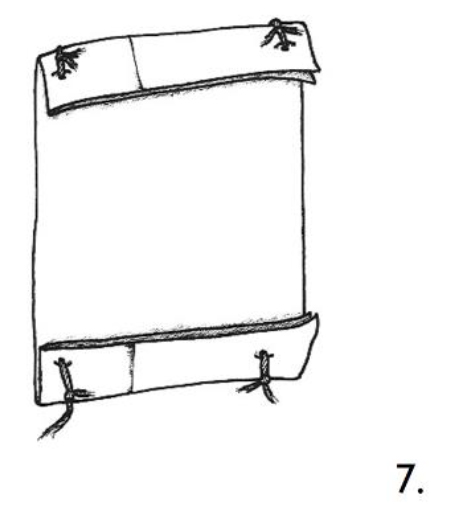

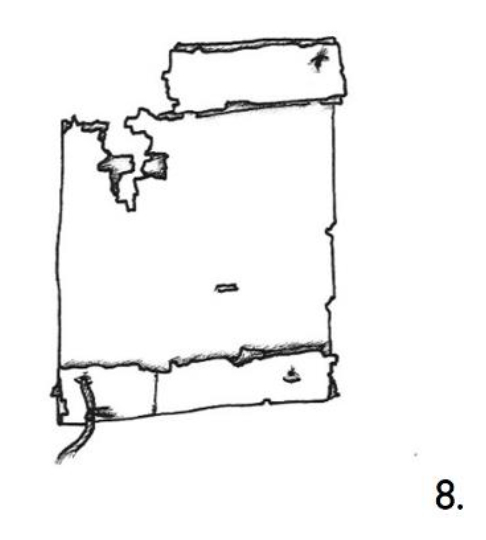

Before I get to the take-aways from the meeting, here’s a quick summary for those who haven’t read the essay by the Graz team: After multispectral photography and further study, the authors maintained their overall conclusion that we have a bifolium of a codex, but they also adjusted some key details of the earlier announcement. In terms of new evidence: The multispectral imaging significantly increased the amount of legible text on the papyrus and also showed that ink transfer had taken place between the two sides of the papyrus, suggesting to the authors that the papyrus was folded closed while the ink was still wet. In terms of changes: The thread that was at first thought to be part of the binding was reinterpreted as one of four tackets that had at one point sealed the folded papyrus (see images below), and the original proposal of binding through the central fold was adjusted in light of what the authors take as evidence for a stab binding (two holes on either side of the central fold). This short description simplifies the authors’ detailed discussion of a series of holes and evidence of folds in the papyrus. In the end, the authors explain the physical evidence of the present condition of the papyrus by discussing its “lives” in 12 steps in their nicely illustrated Figure 14, which I reproduce below with their captions:

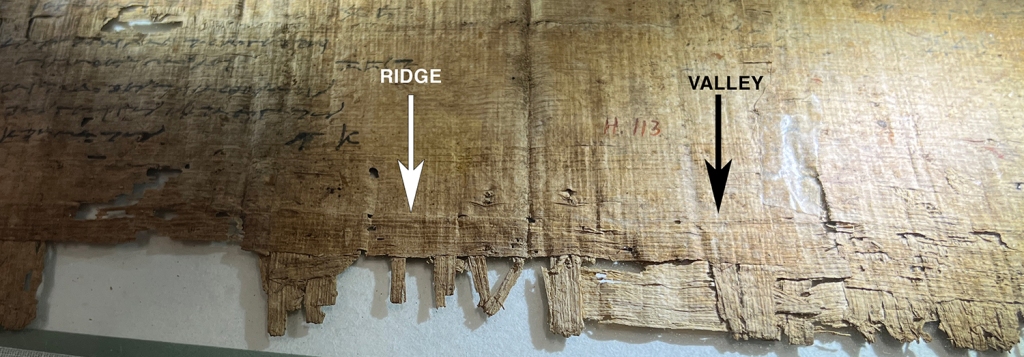

Coming in to the meeting I was a bit skeptical of parts of the authors’ reconstruction (specifically, steps 3-7) and wanted a closer look at the many holes in the papyrus. But I have come away with a sense that we are looking at something quite interesting here, even if I’m not fully on board with the idea that we have the remains of a codex. Because I had never seen a document folded and tacketed in exactly the way the authors describe, I was doubtful about this point, but I’m now inclined to agree that this seems like a good explanation of the physical remains, namely the fold patterns, the presence and position of the thread, and the directions of puncture shown in the various pairs of holes. The fold patterns in particular were clearly visible under raking light.

None of us who were present could point to any parallels for this sort of thing (Ptolemaic accounts produced on a bifolium that was subsequently sealed and tacketed in this manner). But then again nobody would have thought to look for evidence of such parallels before now.

Whether such a document was ever one of several bifolia joined together to form a codex was a matter of considerable debate. Essentially, that portion of the authors’ argument depends upon the interpretation of a single pair of holes in the papyrus, which the authors read as evidence of a stabbed binding that went through the folded papyrus from front to back (the corresponding pair of holes in the upper half of the papyrus would have been in a portion of the papyrus that is now lost). Are these holes evidence of a stab binding? I think more work is needed to clarify this point. But after having had a close look at the papyrus, I would say that I’m open to being persuaded.

The meeting raised many questions: What visual evidence is left by the pressure of a thread against the edge of a hole in papyrus? Can we have a “clean” typology of holes in papyrus (what if an insect has a go at the edges of a hole that was originally created by a needle?)? Under what circumstances does ink transfer occur? Could the process of making cartonnage cause it? More generally, what do we actually know about the process of making cartonnage? And what do we actually know about early twentieth-century processes of dismantling cartonnage? How, exactly, did they do it back then? And, maybe most interesting for me: How much can we really rely on analogies from the behavior of modern, commercially produced papyrus (in terms of folding, piercing, and interacting with thread, for example)?

In short, we have more thinking to do.

As I reflect on the discussions of the last couple days, I’m reminded of Grenfell and Hunt’s early encounter with the remains of a single-quire papyrus codex, which I’ve mentioned here before. Grenfell and Hunt were at first puzzled by a papyrus fragment containing just bits of the very beginning and the very end of the text of the Gospel of John, but they eventually settled on what seems to be (now, in retrospect, to us) the obviously correct conclusion: Their papyrus was the surviving fragment of an outer bifolium of a codex containing the gospel composed of a single, thick quire. But to Grenfell and Hunt, this kind of construction was a surprise:

“Such an arrangement certainly seems rather awkward, particularly as the margin between the two columns of writing in the flattened sheet is only about 2 cm. wide. This is not much to be divided between two leaves at the outside of so thick a quire. But as yet little is known about the composition of these early books.”

My takeaway from this was that “as usual, Grenfell and Hunt were willing to be surprised and recognized that many of their expectations might be overturned by the vast amount of new evidence they were uncovering in those early days.”

Examining this papyrus in Graz together with a diverse group of experts encourages me to remember not to stifle my own willingness to be surprised when a critical evaluation of the evidence warrants it. It’s important to keep an open mind when presented with a confounding piece of evidence.

Very good thanks a lot!!

freundliche Grüße von Sylt

Alexander Schick

What you say in your closing paragraph is SO important.

This is fascinating! Thank you for your time and sharing. I wonder what the purpose of undoing the binding was. Was this common practice? Was it an attempt for them to preserve a manuscript? Or possibly for a particular ritual?

Jeff Cunningham

In their longer essay, the authors write: “Self-contained records like this one were eventually removed from the notebook by undoing the stab sewing, dismantling the notebook. Our bifolio was then sealed by folding up the sides and securing these with tackets. This could have been done as a way of protecting sensitive information, archiving the document, or sending it to a relevant party (eg. debitors or creditors)” (p. 18). I’m not aware of any evidence for a practice like what is proposed here–taking apart a bound codex to use the individual bifolia in this way. When codices are taken apart into separate bifolia in later periods, the loose bifolia are sometimes rebound into a new codex, washed or scraped to be reused to copy a new text, or chopped up for use in the binding of other codices.

A thoughtful and clear report, thanks! julia