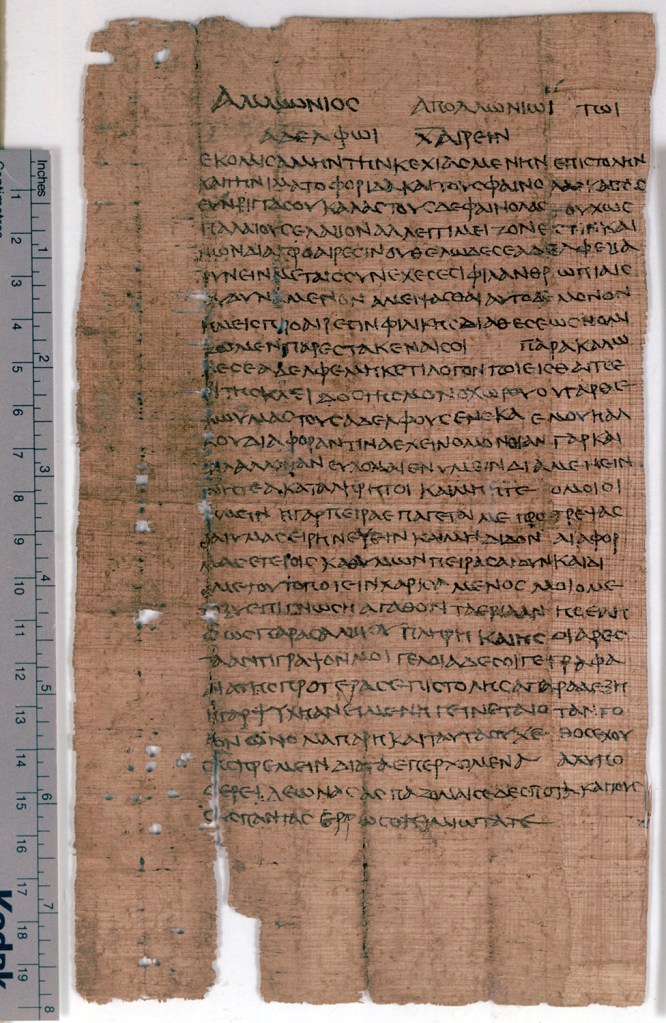

In literature about the process of papyrus production in antiquity, the word χαρτοποιός (“papyrus maker” or “papyrus roll manufacturer”) comes up with some frequency. What’s odd is that its role in the discussion is out of proportion to its attestation. The term appears in only two search results on papyri.info, and both have some problems. The first instance is P.Tebt. 1 5, a list of edicts of Euergetes II from the year 118 BCE. The relevant section is a list of different types of workers who are exempt from a requirement–textile workers (wool weavers and others), pig herders, goose keepers, makers of oil, beekeepers, and brewers. The relevant lines are here in the form they appear on papyri.info:

…καὶ τανυφά[ντας πάντ]α̣ς καὶ τοὺς ὑοφορβοὺς

καὶ χηνοβο(σκοὺς) κ[αὶ χαρτοποιοὺ]ς(*) καὶ ἐλαιουργοὺς καὶ

κικιουργοὺς καὶ με[λισσουργο]ὺς καὶ ζυτοποιοὺς…

The asterisk indicates that the reading given in this line on papyri.info differs from what the original editors (Grenfell and Hunt) proposed, which was this:

καὶ χηνοβο(σκοὺς) κ[αὶ. . . . . . . . . . ]ς καὶ ἐλαιουργοὺς καὶ

In support of the restoration of [χαρτοποιού]ς, the Berichtigungsliste gives references that lead ultimately to a single Russian work that I have been unable to track down. The reference is given in the following forms:

- W. G. Borukhovich, Papirusnye svidetelstva ob organizacii proizvodstva i prodaje charty ν Egiptie vremeni Ptolemeev. Problemy socialno-ekonomicheskoy istorii Drevnego mira. Sbornik pamyati akademika A. I. Tiumeneva = Papyrus-testimonies concerning the organization of the production and sale of charta in Egypt in the times of the Ptolemies. The problems of the social and economic history of the Ancient World. A collection of essays in memory of the academician A. I. Tiumenev. Moscow-Leningrad, 1963, pp. 271-287.

- D.G. Boruknovič, Papyrologische Quellen zur Organisation der Herstellung und des Handels mit Papyrus im ptolem. Ägypten, Gedächtnisschrift für A.J. Tjumenev, 1963, S. 271 ff.

(If anyone who has access to the chapter and reads Russian wants to offer a translation of the relevant bits, that would be great!)

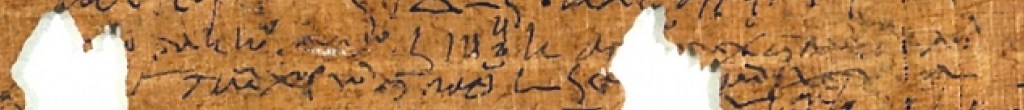

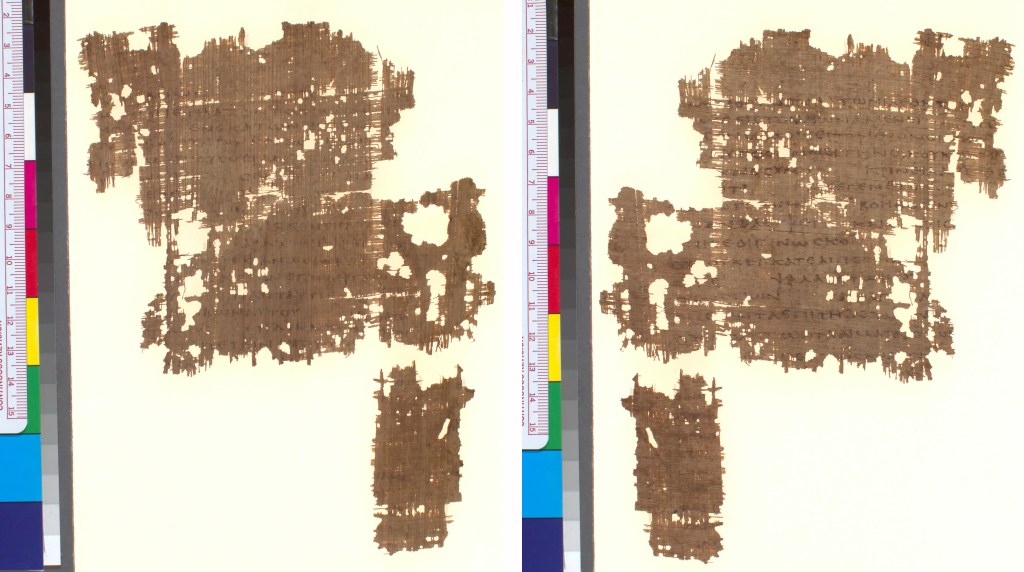

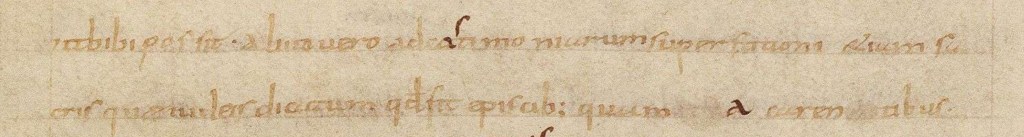

In any event, a quick look at an image of the papyrus suggests that Grenfell and Hunt’s more conservative transcription is probably safer, as there really is just a light trace of (maybe) a final sigma and nothing else. The dotted line is where our missing word would be:

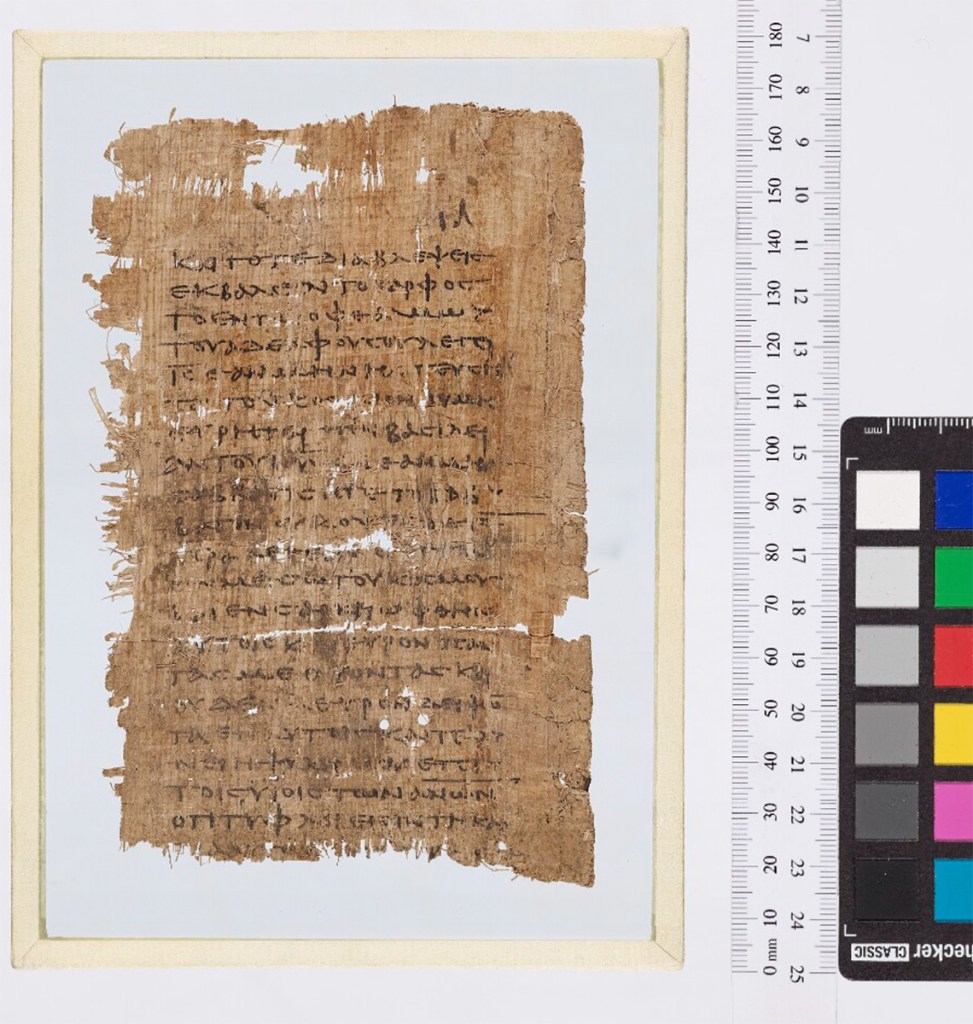

The second occurrence is in another papyrus from Tebtunis, P.Tebt. 1 112 (=P.Tebt. 5 1151), an account of income and expenses. We have a little more to work with here in the relevant lines:

Ἁρφαήσει μαχί(μωι) ὁμοίως τι(μῆς) χαρτῶν εἰς συ(μ)-

πλήρωσι<ν> τῶν διαγεγρ(αμμένων) τῶι χαρτ[ο]πο(ιῶι) Γω

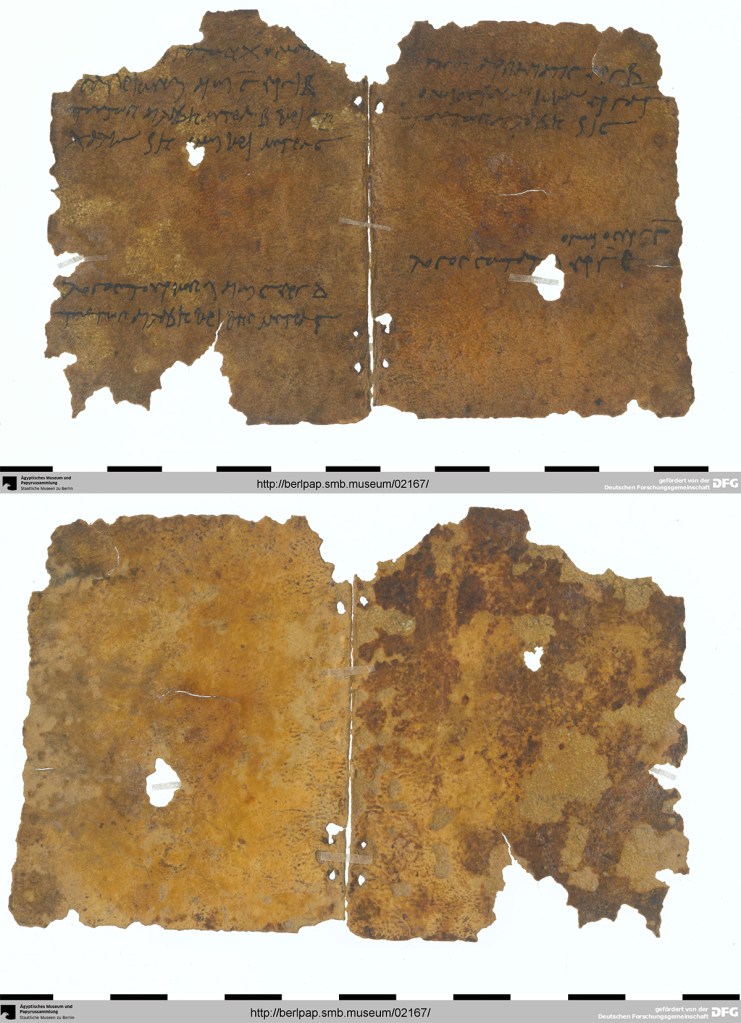

We clearly do have a χαρτ- word here, and the context, in which expenditures for other writing materials is discussed, lends itself to a word meaning “seller of papyrus,” but not so much “maker of papyrus.” And I hate to disagree with Grenfell and Hunt, but I cannot convince myself there is a pi and an omicron in where they see it after the lacuna in χαρτ[ο]πο(ιῶι) Γω:

I don’t know of any other proposed restorations here. Ulrich Wilcken (Grundzüge, 1.1.255) resolved the abbreviation differently, proposing χαρτοπό(ληι) = χαρτοπώ(ληι), “papyrus seller,” but this word is just as poorly attested (and doesn’t solve the pi–omicron problem). Another thing that bothers me here is the meaning of διαγεγρ(αμμένων) (I’m not sure why papyri.info has διαγεγρ(αμμαμένων) with an extra syllable here). In his re-edition of the papyrus, Verhoogt translates as follows:

“To Harphaesis, armed guard, ditto, as the price of rolls of papyrus for payment in full of the 3,800 paid to the papyrus-maker,

Verhoogt presumably takes διαγεγρ(αμμένων) as a synonym of διαγρ(αφή) (in this context meaning “payment”), which occurs a few lines later in reference to papyrus rolls. But is that the best way to handle this? As Verhoogt notes, the other papyrus rolls mentioned in this account are specified as ἄγρ(αφος), “blank,” “unused,” or “uninscribed.῾ It stands to reason that in such a context, διαγεγρ(αμμένων) would mean the opposite: “used” or “inscribed” (although I don’t know of any parallel usages of this word in this way). If this is the correct understanding, it would raise the question of whether we should imagine buying used papyrus rolls from a “papyrus maker” or a “papyrus seller.”

In any event, I don’t spend a lot of time reading Ptolemaic documents, so I don’t really have any insight into how that gap might be filled in an intelligible way, but given its lack of existence elsewhere in the papyrological record (so far), and the surviving ink traces here, I’m a little skeptical of χαρτοποιῶι.

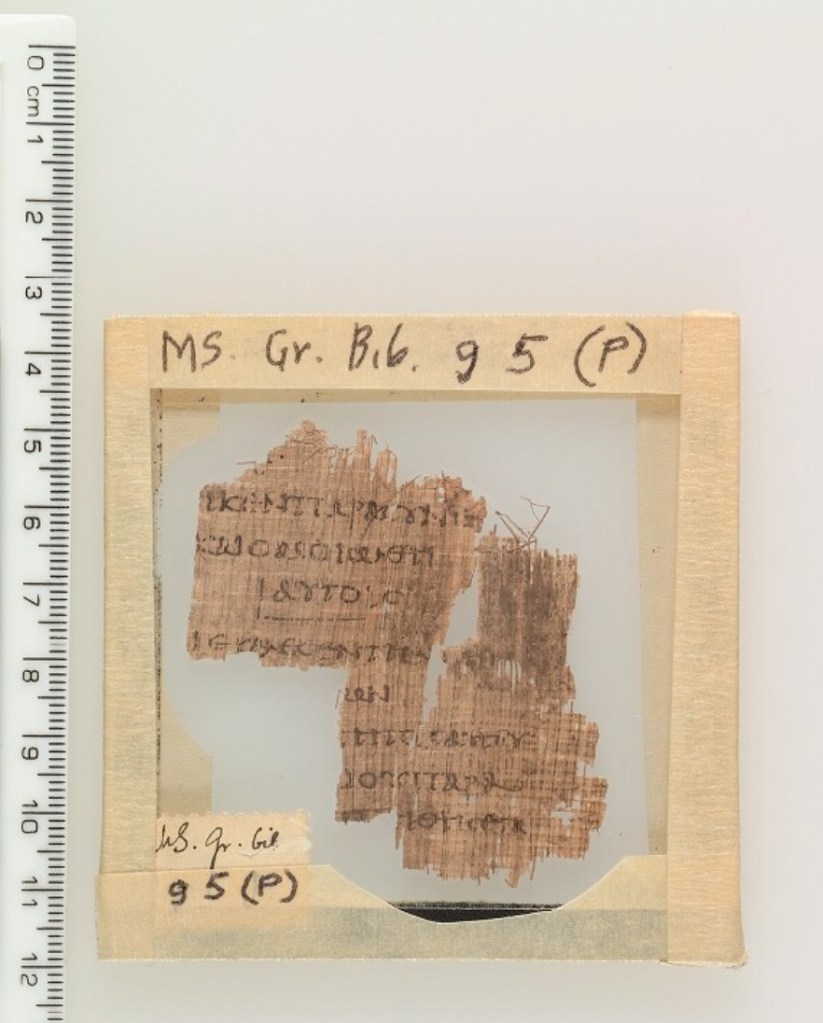

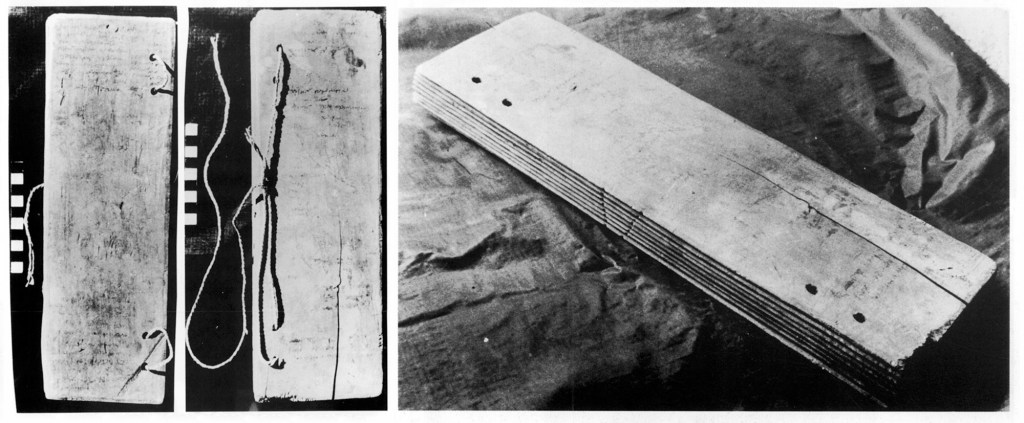

In an article in ZPE from 2016, Menico Caroli added two more potential candidates for possible occurrences of χαρτοποιός, P.Wisc. 1 29 and P.Flor. 3 388. P.Wisc. 1 29 is a highly fragmentary list written on the back of another document. The relevant line is quite damaged, and the quality of the published image is not great. The transcription from papyri.info is below, along with the relevant section of the image.

κ̣δ Ἀλλοῦτι χαρ̣τ̣[ο]\π̣/[(ώλῃ)] (ἀρτάβη) α

The original editor suggested χαρτοπράτῃ as a possible alternative reading for χαρτοπώλῃ. The word χαρτοπράτης (“papyrus seller”) has the virtue of being clearly attested in unabbreviated form in two papyri, but the drawback is that both these papyri date to the seventh century CE at earliest (BGU 1 319 and P.Berol. inv. 2749). The term also appears in Latin transliteration (chartopratis) in the Justinian Code 11.18. Caroli, however, suggests that we have here another instance of χαρτοποιός, but given what we have seen of the overall insecure attestation of this word, proposing such a reading here just begs the question.

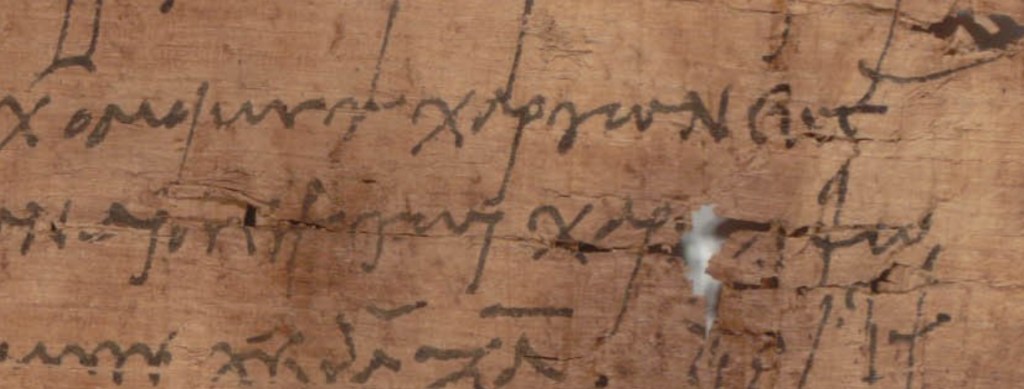

P.Flor. 3 388 is a set of private daily accounts from the late first or early second century CE. The online image of this piece is not especially good, but I supply it below with the text of the relevant lines from papyri.info:

[ -ca.?- ] ̣[ -ca.?- ] ̣ ̣σακκω̣( ) αὐτῶ(ν) (δραχμαὶ) ιβ ὀβ(ολοὶ) κ ἀρ[γυρι]κ(οῦ) ἔσχο(ν) δι(ὰ) Πλουτ(ᾶτος) ὀβ(ολοὺς) ε λοιπ( )

[ -ca.?- ] γ τιμ(ῆ)ς χαρτοπ( ) δι(ὰ) Παθώ(του) 𐅵 (δραχμῆς) ε[ἰς τ]ιμὴ(ν) ἰχθύω(ν) (δραχμὴ(?)) α

The editor left the abbreviation unresolved. Caroli suggests χαρτοποιός. But again, there is no clear reason to resolve the abbreviation in one way or the other.

The TLG doesn’t help much either, giving just one hit, Constantine Porphyrogenitus (905-959 CE), De administrando imperio 52.11, in which χαρτοποιοί are listed among other professions (sailors and murex fishers) that did not provide horses in a levy in the Peloponnese in the tenth century. There is no indication of the exact meaning of the word. “Papyrus maker” seems unlikely in such a temporal and geographic setting, but if the term refers to another writing surface (parchment or paper), surely it must have had a prehistory of some sort in which papyrus figured?

The Lexikon zur byzantinischen Gräzität, if I understand the entry correctly, adds a reference to a particular manuscript of Theodore of Stoudios (8th-9th century): “A. Dobroklonskij, Prepodobnyj Feodor I (Odessa 1913) 413adn.1.: Theod. Stud., catech. magn. in cod. Patm. 112.” I have not had a chance to track this reference.

So, there are still some references to check, but at this point, I don’t think I’m totally convinced that we have any attestations of this word before the medieval period.

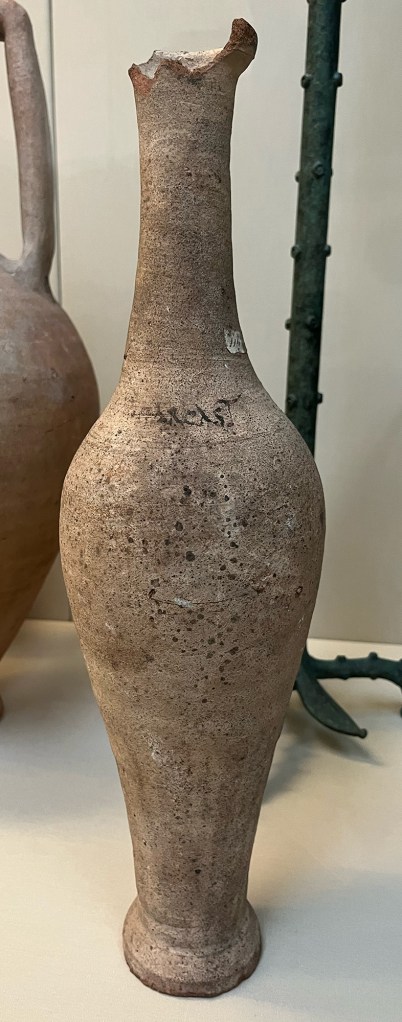

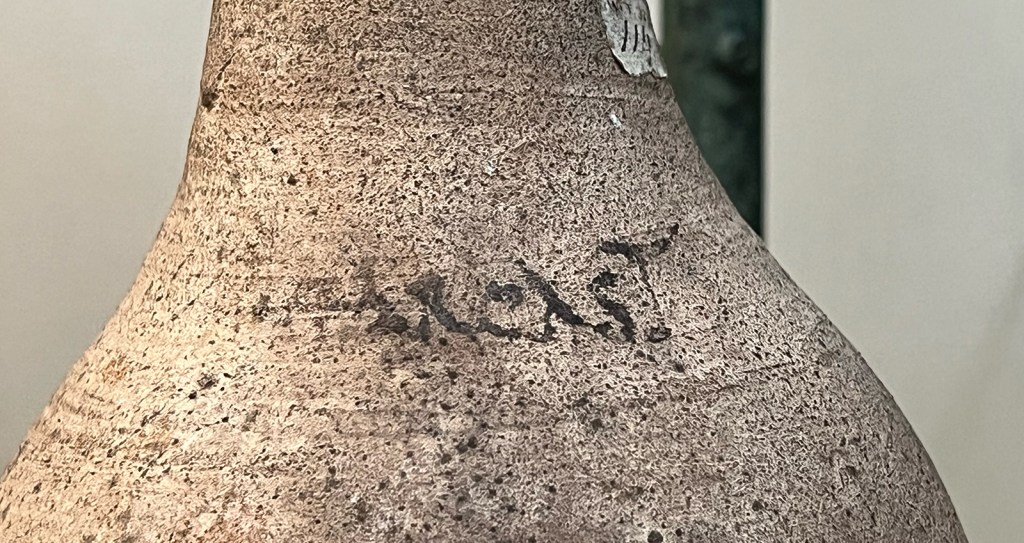

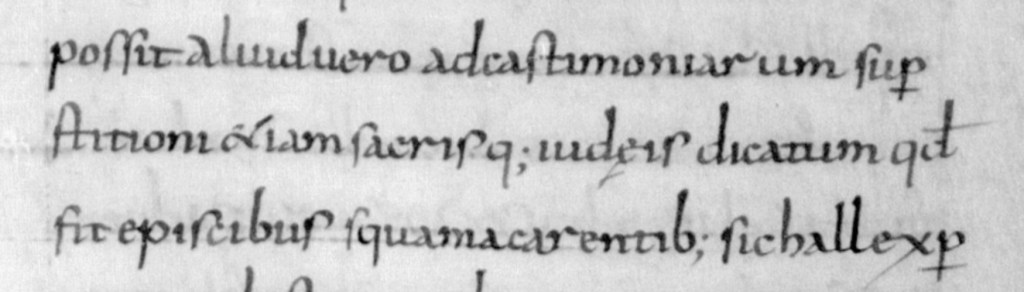

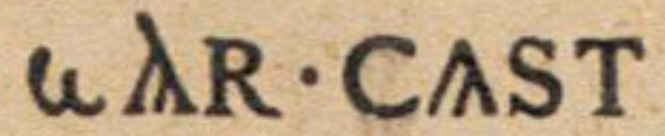

and said to come from the temple of Mercury–presumably the temple of Genius Augusti) and CIL IV Supp. 5662 (published as CAR CɅST / SCOMBRI/////FORTUNATI). Also possibly CIL IV Supp. 5660 (published as ///////VM CɅST) and 5661 (published as gɅR CɅST / aB VMBRICIɅ FORTUNATA). The other terms represented in these dipinti deal either with the type of fish used (scomber = mackerel) or the specific producer (Umbricia Fortunata is attested on other garum jars; hers was a family associated with fish products).

and said to come from the temple of Mercury–presumably the temple of Genius Augusti) and CIL IV Supp. 5662 (published as CAR CɅST / SCOMBRI/////FORTUNATI). Also possibly CIL IV Supp. 5660 (published as ///////VM CɅST) and 5661 (published as gɅR CɅST / aB VMBRICIɅ FORTUNATA). The other terms represented in these dipinti deal either with the type of fish used (scomber = mackerel) or the specific producer (Umbricia Fortunata is attested on other garum jars; hers was a family associated with fish products).